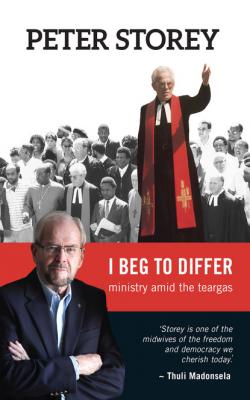

I Beg to Differ. Peter Storey

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу I Beg to Differ - Peter Storey страница

>

>

PETER STOREY

I BEG TO DIFFER

Ministry amid the teargas

Tafelberg

FOR ELIZABETH,

the sons and daughters she loved,

the grandchildren she cherished,

and

Sophie Elizabeth

who bears her name.

A candle-light is a protest at midnight,

It is a non-conformist.

It says to the darkness,

‘I beg to differ.’

Samuel Rayan

Your Will be Done (Singapore: CCA, 1984)

Introduction

The Train to Koedoespoort

The boy loved the train.

He loved the enormous Class 23 locomotive with its six powerful driving wheels, burnished copper tubing and swishing pistons, all producing an exhilarating mixture of belching smoke, roaring noise and hissing steam. Sometimes, when the load being hauled to or from Lourenco Marques was heavier than usual, an even bigger, four-eight-two configured Class 15E would do the job.

The train was important in his life. None of his classmates rode a steam train to school. Each morning he would wait – on the cinders, never on the platform – and when the train pulled in, his three friends would open the door and he would climb the vertical steps to join them. They were English-speaking kids from Cullinan diamond mine, fifteen miles further up the track. The heavy wooden door would close with a satisfying ‘thunk’ when he came on board. It was always one of the 2nd Class compartments, a world of dark varnished wood and upright green leather South African Railways seats, with chrome luggage racks, and faded sepia photographs of the Blue Train roaring across the Karoo or the Orange Express climbing a Drakensberg pass.

Twice each day this was their world.

They would like to have been closer to the smoke-belching locomotive, but that was not possible. The 2nd Class coaches were in the middle of the train, neatly sandwiched between 3rd Class, nearest the front, and 1st Class, furthest away from the cinders and grime. Important people sat in 1st Class, and 3rd Class was where the natives sat. They knew that.

There were other schoolchildren on the train. They also rode in 2nd Class, but never with the boy and his friends. They wore a different coloured school blazer and tie, and spoke Afrikaans, a language he and his friends struggled with for one class each day under the eye of their least favourite teacher – and then forgot. The Afrikaners went to a different school and were part of a different world that the boy and his friends had no interest in exploring. They were not aware of any overt hostility, just indifference. Sealed in their safe compartment, looking out through the familiar Springbok emblems etched on the windows, they and the Afrikaner strangers and the special people who sat in 1st Class were carried in a rush of noise and steam and smoke across the dry brown veld.

The natives were on the train too. Unlike his friends from Cullinan, the boy had been taught to call the natives by another name; he called them ‘Africans’. His friends usually used other names too, words like ‘kaffer’ and ‘munt’, but were careful not to do so around him. They were a little awed by his father being a church minister and amazed that the boy and his family lived among the natives. The boy played on their respect, of course, and also the superior knowledge he had about the natives. Above all, he enjoyed them knowing that his father was not just an ordinary clergyman, but a ‘Governor’. His title was Governor of Kilnerton Institution, where hundreds of Africans lived. They came from all over the Transvaal and further afield to be educated by his father and other good and wise people.

The boy’s journey was always too brief. He envied his friends’ longer ride to Cullinan. Their dads worked on the diamond mine there. Travelling home, he was the only one to get off at Koedoespoort station, again dropping down to the cinders on the opposite side from the station platform. He would stand right there, alongside the creaking bogeys as the locomotive took the strain and the coaches stretched and complained their way into motion. Then he would begin his walk home. It was the same every day.

But not on this day …

This day, from the time they boarded the train in Pretoria things had been different. As they steamed through its eastern suburbs, the boy and his friends could hear the singing and shouting of the Afrikaner youths. Muffled though the sound was by the compartment walls, it was louder and more raucous than anything they remembered. Although it was early in the season, perhaps Afrikaans Hoërskool had won an important rugby match? Perhaps that explained their excitement.

This day, when the boy got down alongside to the tracks, he stood as usual to watch and feel and hear the train pull out. As it began to move, and the coaches slowly passed him, the shouting he had heard earlier became an ugly jeering. When he looked up it seemed that all the Afrikaner youths were leaning out of their carriage. They were waving little flags he didn’t recognise, and they all seemed to be shouting at him and the words came thick and fast, “Kaffer-boetie! Kaffer-kind! Nasional wen! Malan wen! Apartheid kom!” The boy was still looking up in shock when someone hawked, and spittle began to fly. It seemed that the whole train was spitting on him. He stood, covered in their spittle, transfixed by confusion and shame, until the clickety-clack of the guard’s van faded into the hot autumn silence. Then, fighting back tears, he ran home through the tall yellow grass, desperate to know what wrong he had done to deserve such derision.

Later on this day, the boy’s father told him that a change had come in the land. From this day, there would be a new government consisting entirely of Afrikaners with no love for English speakers and a different way of treating people, especially the Africans. There had been an election; people called ‘Nationalists’ had won, and they resented those who worked for the welfare of the Africans. “It’s because you got off at this station, son. That’s what made the difference. They know that only people involved with Africans get off here.”

The boy didn’t understand much, but he knew that his world had changed; it had been invaded by a new and dark foreboding. The happy rides encapsulated in that safe and familiar compartment would never be the same. He had got off at Koedoespoort station – that’s what he had done wrong. That’s what made the difference.

It was May 1948 and the boy was nine years old.

1

The South African English

People like me are usually called English-speaking South Africans, but my generation was more accurately the last of the South African English. We were born in Africa and our ancestors of the last 200 years lie buried in African soil, but we never totally belonged here. The haunting beauty of our birthland – bold brass skies and scudding cumulus, dusty, gold-grey veld and dry brown sandstone, thorn trees and the smell of dust after rain – all these may have crept into our hearts, but they were not indigenous to our souls. Our inward beings were formed less by the geography of our birth than by the heritage, values, and rituals of a small island in the mists of the Northern hemisphere. We were proud South Africans, but to be South African was to be in most important ways, British. When