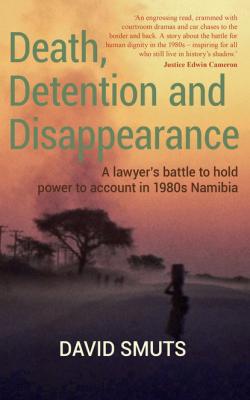

Death, Detention and Disappearance. David Smuts

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Death, Detention and Disappearance - David Smuts страница

tion>

tion>

David Smuts

Death,

detention

and disappearance

A lawyer’s battle to hold power to account in 1980s Namibia

Tafelberg

To the memory of my parents.

And to the many who courageously resisted.

‘The struggle of [people] against power is the struggle

of memory against forgetting.’

Milan Kundera, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting1

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering.

There is a crack, a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in.

Leonard Cohen

‘Anthem’, 1992

PROLOGUE

The historical setting

Colonialism came late to Namibia. The country’s rugged coastline, aptly called the Skeleton Coast, is littered with shipwrecks. Stretching inland for some distance from this uninviting shoreline is the world’s oldest desert, the sublime Namib, which gives the country its name. On the eastern side of Namibia lies the vast expanse of the Kalahari Desert, which extends deep into neighbouring Botswana. These two deserts cover much of Namibia’s territory, making it the most arid country in sub-Saharan Africa. This geography may have discouraged colonial powers until the late nineteenth century. But the discovery of diamonds and other minerals changed that.

Imperial Germany was the first to stake a colonial claim by proclaiming a protectorate around the port of Angra Pequena on the southern coast in 1884 at the behest of a trader, Lüderitz. The harbour settlement was later called Lüderitzbucht after him. The German colonial area was expanded and the boundaries of German South West Africa became settled after treaties with Portugal in 1886 and Great Britain in 1890.

The land policy of the German colonial period was directed not only at depriving the indigenous population of land for colonial settlement, but also – according to leading historian André du Pisani2 – at destroying the political autonomous structures of the indigenous people. This was perpetrated by removing people from land and then dumping them on reserves of crown land as an effective way of exercising political and economic control over them. In this way, groups were fragmented and their leadership undermined. This approach was essentially followed and became intensified by the successive South African governments that replaced German colonial rule in 1915.

German policies of land deprivation and other abuses led to uprisings from 1904 to 1907. These were brutally put down, culminating in the infamous proclamation of extermination of the Herero by Governor Von Trotha (the ‘Vernichtungsbefehl’) and the genocide that followed. War crimes were also perpetrated against the Nama and Damara communities, which had revolted against German rule in the uprisings of 1904–1907.

Although German colonial rule is primarily remembered for the genocide and war crimes perpetrated against Namibia’s people, the legal system imposed on the territory was also oppressive and operated against the indigenous people. German colonial rule did not, however, interfere with land tenure north of the ‘red line’. Owamboland was instead to provide a pool of cheap labour. A migrant labour system was introduced which would, subject to refinements and adaptations, remain enforced until the 1970s. A pass law regime was rigidly enforced upon black inhabitants over the age of fourteen from 1907. The Germans passed a law that prevented blacks from owning title to property, or even horses or cattle, without the governor’s consent. According to Pakenham,3 those found guilty of stock theft under German law could be (and frequently were) sentenced to death after trials by all-white settler juries.

This was the nature of the legal system inherited by the South African government when it invaded the territory in 1915 following the outbreak of the First World War, marking the end of German rule. The territory was governed under military rule by South Africa until 1920.

The League of Nations was established after the end of the First World War and, under the Treaty of Versailles, the territory became a class C mandate entrusted to South Africa as mandatory power as a ‘sacred trust of civilisation’ with ‘full powers of administration and legislation’ over the territory ‘in the best interests of the indigenous population’. The South African parliament passed legislation to formalise the mandate in 1919 and military rule formally came to an end with the appointment of an administrator in 1920. German law ceased to apply and Roman-Dutch common law as applied in South Africa became the legal system in the territory, together with statutes enacted for or applied to Namibia.

From the outset of the mandate, South Africa’s government proceeded to rule the territory as a fifth province of South Africa. The influx of Afrikaners from the Boer republics during German times increased after South Africa took control. Large tracts of land were allocated to these white settlers for farming.

Native reserves continued and were expanded in size after South African rule, especially after the National Party won power in 1948 and implemented its far more rigid racial segregation policy of apartheid in Namibia as well. The native reserves were controlled through selected tribal leaders who acted under the control and supervision of white officials of the South African government. The reserves under German rule were pockets of mostly small pieces of land for the Nama, Damara and Herero people. This system became more formalised and consolidated under South African rule after the Odendaal Commission, which, in 1964 recommended the imposition of its homeland policy of ethnically separated homelands, implemented in 1968. Apartheid by then affected every facet of life in Namibia.

The highly regulated and resented migrant labour system, the lack of access to land (after the initial deprivation) except in reserves without tenure, and massively inferior spending on public services on racial and ethnic lines meant that the profound level of inequality inherited from German colonial times became more entrenched and was further compounded by apartheid policies. The huge inequality in education and other public spending continued right up to independence in 1990, despite the installation of two interim governments with limited powers during the 1980s.

After the end of World War II, the United Nations organisation (UN) was established in 1945 and the League of Nations was formally dissolved the following year. The UN Charter did not, however, deal directly with former mandate territories, although the expectation was that these would form part of the system of trusteeship envisaged in the Charter. South Africa resisted trusteeship, however, and preferred incorporation of the territory into South Africa, a move supported by the all-white legislative assembly established for the territory. Thus began years of dispute over the territory between the UN and South Africa.

The National Party government furthered a policy of incorporation by providing for representation in the South African parliament to white inhabitants of the territory in 1949 and became more and more defiant in its dealings with the UN and the international community after 1948.

As decolonisation elsewhere in Africa and Asia led to new members of the UN adopting a more militant position against South Africa, there was a rise in black political movements and resistance within Namibia. The OPO (Ovamboland People’s