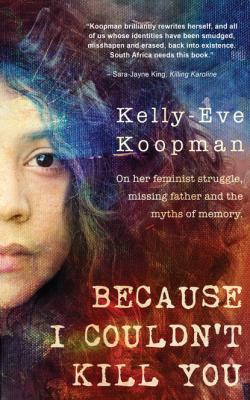

Because I Couldn't Kill You. Kelly-Eve Koopman

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Because I Couldn't Kill You - Kelly-Eve Koopman страница

“Kelly-Eve Koopman’s memoir about the search for her lost father will break your heart and stitch it back together with luminous prose. Part memoir, part queer feminist anti-capitalist manifesto, Koopman has written a story for our times! Her elegant writing dazzles as it shines a light on the darkest crevices of broken families and psyches. It is a story of love lost and remade, in which the personal and political overlap with heartrending clarity. A brave and searingly honest narrative of a young black woman charting a healing course through our post-transitional society still grappling with the legacies of structural and intimate violence. Koopman has a rare gift and is a talent to watch!”

– Barbara Boswell, author of Grace

“This book serves as both the prescription and the medicine to the historical ills endured by women of colour. It is a love letter to our mothers, our grandmothers, their grandmothers (and ourselves) and, simultaneously, a cease and desist letter to the transgenerational trauma which for too long has taken root in our bodies. Koopman brilliantly rewrites herself, and all of us whose identities have been smudged, misshapen and erased, back into existence. Hard and heart-breaking, South Africa needs this book.”

– Sara-Jayne King, author of Killing Karoline

“Kelly Koopman is a brilliant watcher and gifted wordsmith. Because I Couldn’t Kill You is sensitive, brave, spiritual and sexy. An insight into one of Kaaps’s sharpest minds.”

– Chase Rhys, author of Kinnes

Because I Couldn’t Kill You

A Memoir

Kelly-Eve Koopman

PROLOGUE

A brief history of sameness

I have come to my childhood home. To fight fair with writer’s block on home turf. To pin down the evasive muse at the source of my creation, amongst familiar old ghosts, amongst the dusty artefacts of self, the porcelain dolls, the illustrated encyclopaedias, the well-worn single bed that will always recognise my shape. Here where I am brought coffee in a matching cup and saucer, and the sheets are quietly turned down in anticipation of a good night’s rest, where there is still white bread, and white sugar, and koe’sisters awaiting their turn to be syrupped and zealously rolled in coconut. This is why I am here, in the quiet of the suburbs that in my teens I could not wait to run away from. Glenhaven, a place where, at first glance, it seems that time has generously stood still.

This has been a coloureds-only suburb for about 45 years. Coloureds only as declared by the NP Government, a place which, like many places, has stayed exactly the same decades later. The first black and first white families moved in pretty much simultaneously when I was in my early teens, sending a minor shock ripple through the neighbourhood. Soon afterwards, because of Glenhaven’s proximity to UWC, the university that my mother dedicated her academic career to, there was an influx of trendy young black students sharing the well-priced, neat and secure houses. They walk through the streets at night, arms confidently linked, talking and laughing, and have parties with loud gqom music. While the area is home to people who recognise that it’s not good etiquette to be outright racists, there is the generic, familiar tone of othering when referring to the young black newcomers. There has also been a marked increase in the number of neighbourhood-watch-type WhatsApp groups and murmurs about ‘culture clashes’ – words that despite their best efforts can barely veil the implicit racism.

The neighbourhood has always more than tolerated the existence of coloured teenagers and 30-year-old baby daddies who, despite having mid-managerial level careers, never move out of the bed and breakfasts of their mommies’ homes. These youths who park cars outside the tennis courts and skelmpies drink in their dropped cars, recognisable by the murmuring bass of deep house (very similar to gqom but regarded with much more tolerance) or turn up in very clean and well-furnished yaadts when their parents are away on holiday to Club Mykonos, there by Langebaan, not to be confused with Mykonos in Greece – or in Thailand even, if your parents are those who have a double-storey house and a pool. The perfunctory trip to Thailand has become like the hajj of middle-class coloured culture, modest conspicuous consumption in the form of a Contiki trip.

These mildly disaffected youths are tolerated, there is the mutual understanding that these are kids under the firm hand of parents and grandparents, who are expected to for the most part conform to the code of the suburbs and move out to become accountants and HR managers, buy in the neighbourhood, move on to other respectable coloured suburbs, or perhaps even permeate the more gourmet vestiges of the Boerewors Curtain – the Durbanville Hills and the Stellenbergs, where the white Afrikaans Janse van Rensburgs will regard this new influx of unsightly coloured young professionals with the same attitude the Jacobs of Bellville South regard the influx of young black scholars.

My grandparents were one of the three first families to move into the area, the founding fathers, pioneers navigating the rough terrain from working to middle class. They started building the closest they could get to their dream house on a sandy vacant treeless plot flanked by the nylon spinners’ factory on one side. Safe and sequestered and still technically on land that was the Cape Flats, this was the perfect place to engineer their painstakingly difficult ascent into the brown middle class. My grandmother went to teachers’ training college – the pinnacle of a coloured woman’s education at the time was to be a respected Sub A teacher. My grandfather started off as a worker, quickly climbed the ranks as a factory manager and found himself gratefully able to afford living-room suites, Christmas presents and good educations for all three of his bright, lucky children. Their house, which they named Oasis, was the first one built on the street, ranch style with big windows, a gleaming stoep and a meticulously cultivated rose garden. The house lived up to its name, and almost every one of their children and grandchildren at some point, going through a difficult time, seeking some kind of refuge and release, has returned to its sturdy suburban walls.

I too return to write this book. I dare not spill my coffee on the pristine white cloth on the dining-room table, with small roses embroidered at the edges. I have a view of what was once the lawn but has now been recently paved. My grandparents, who have always been very attentive to their plants, have, after much deliberation, laid over the sparse, tufty expanse that has slowly succumbed to the inevitable dereliction of the drought. Across the road is the ‘parky’ which has managed to evade any kind of government attention and still boasts the same rusty roundabout and precarious tyre swings from my childhood. The sepia fragments of faded, broken Black Label and Brutal Fruit bottles are relics, abandoned by coloured teens who have now gone on to drink Merlot and buy Webers.

The neat, sprawling ranch-style houses and spilt-level bungalows overlooking the parky’s offensively disordered archaeology cast their eyes down in shame and disdain. This is a nice neighbourhood after all, and if it weren’t for the evidence of the parky and marked absence of trees, it could even be mistaken for a white area. The houses have heavy eyelids weighted down with netting and thick, frilly curtains that are meant to stop outsiders looking in, but do not prevent insiders from looking out. In the centre of the parky, squat and with a prowess that seems to defy the inevitability of power cuts, there is the militaristic-looking kragbox that I was always told was too dangerous to approach. It is lovingly decorated with the prerequisite graffiti, different names making declarations of love and loathing in different ways but always in the same font. The Helvetica revolution has not yet made its way to the deep North.

My grandfather is in Lenny Kravitzy tinted glasses to protect his eyes post cataract operation – he wears the tints for driving, which he does confidently at 85. He glances