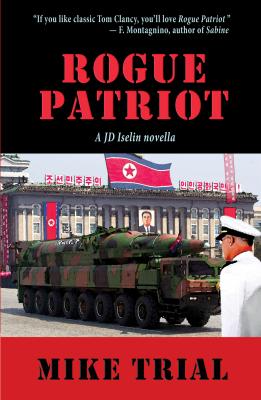

Rogue Patriot. Mike Trial Trial

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Rogue Patriot - Mike Trial Trial страница 4

silently. He almost laughed out loud. Now that he had received his death sentence, the uncertainty was past. A weight of anxiety lifted from his shoulders.

silently. He almost laughed out loud. Now that he had received his death sentence, the uncertainty was past. A weight of anxiety lifted from his shoulders.

Hallam had his driver let him off halfway down the eight blocks that comprised Motomachi Street. A street filled with small art galleries, boutique clothing stores, shops filled with gleaming European-made kitchenware. “Wait for me here.”

The crowd flowed past him, ordinary Japanese people going about their business. What if the North Koreans successfully launched a high ballistic shot at Japan, detonated a dirty nuclear fireball over Tokyo, letting a poisonous cloud of radioactive fallout drift south over Yokohama, bringing slow death to all these people?

Hallam glanced at his watch. The North Koreans were preparing a launch right now. Their nuclear warhead was unaccounted for, most likely being installed on the Tae Po Dong, the target of the attack unknown. And my own government says to do nothing but sit and wait.

A sign at a narrow alley advertised Atelier K, Contemporary Art, one flight up. Hallam went in the door and up the narrow flight of stairs.

The woman seated behind a tiny desk near the door stood and bowed. “Irasshaimase,” she greeted him in Japanese, then in English, “Welcome.”

Hallam nodded, and slowly made his way around the four walls, looking at each painting for a moment before moving on. The woman went down the stairs, then returned a moment later.

The gallery was a single room, twelve by ten meters, hardwood floor, track lights for the art on four walls, a single bench in the middle made of pale Japanese cryptomeria wood.

He was American military so she was undecided as to whether to bring tea, which she always did for Japanese visitors. He moved around the room, thoughtfully examining each painting, then sat on the bench, facing Tomoko’s two darkest paintings. She saw that he sat without fidgeting, with his back straight, so she decided to serve tea as she would a Japanese customer.

She brought it to him with strainer and handleless Japanese cup. “Sumimasen, dozo,” she said, setting it on the tray on the bench beside him.

“Domo,” he replied.

Hallam let his mind unfocus as he stared at the two paintings, one a foggy coastline seen from across a small bay. What appeared to be the exposed rock of a quarry in a small valley. The other painting was a cold bare classroom, eight children in blue uniforms, a teacher, his expression concerned, looking at them from his place at the blackboard. Both paintings were nicely executed but very dark, fearful in tone.

His mind drifted to Dr. Adams’ note. Last week’s tests had confirmed that his cancer was advanced. At that examination, Dr. Adams had recommended his immediate transfer back to Washington. Hallam had told him he would consider it. In the meantime, no one was to be told of his illness.

Hallam emptied his mind, focusing on only this moment, on breathing in and breathing out.

Hallam drank his tea. “I believe the painter of these paintings is employed at the U.S. Navy base. A Miss Tomoko Hayakawa?”

“Yes,” the woman said. She handed Admiral Hallam a short biography printed in Japanese and English. He read it. The artist was Tomoko Hayakawa from his office. Despite her Japanese features, there was something about her that reminded him of his daughter Monica, also an artist.

Hallam approached the woman, “I’d like to buy these two paintings of Miss Tomoko’s,” he told her. The woman bowed her thanks.

“Will it be possible to take them now?”

“Yes.” She took the two paintings down and began wrapping them carefully on the worktable at the back of the gallery.

The photo on the biography captured the same sadness Hallam had noticed in Miss Tomoko’s eyes at the office. Unlike most formal Japanese photos she was looking slightly away from the camera, eyes cast down. He had seen that expression often in his own daughter, Monica.

He could admit it now, his wife Mary had been right after all. He should have chosen a less ambitious career path and spent time with Mary and Monica. He could have changed his career plan, settled for lower rank, and become a satisfied man. The time to make that change had been more than twenty years ago. But he had wanted something more.

Hallam had been at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, getting his master’s degree in Asian geopolitics. He had declined campus housing and rented half of a small duplex in Pacific Grove for himself, Mary, and ten-year-old Monica. Every Saturday morning he and Monica would take a long walk together, down the clean silent streets wreathed in morning fog to Lover’s Point Park, sometimes stopping for a croissant and hot chocolate at the bakery on Forest Ave. Then they would walk the trail along the coast as the sun began to burn the fog away, past the research station, past the Aquarium, and down Cannery Row stopping in this shop and that as their fancy dictated. Then down Alvarado Street in Monterey to meet Mary for lunch under the cypress trees on the patio at Cafe des Ami.

After lunch they’d walk home, and he would study until dinnertime when they would drive to Carmel to try a new restaurant, a new wine. It had been a magical year.

His mind travelled that familiar path of memory, guided by nostalgia and regret. The smell of Monterey Bay, the crowds on Fisherman’s wharf, the quiet of eucalyptus tree shaded streets and the brightly painted Victorian cottages of Pacific Grove. That year in Monterey had been a good one. They hadn’t realized it at the time, but it had been the best year of their lives.

Twenty years later cancer claimed Mary. His career had been stellar. He was already being groomed for politics after the Navy. But when Mary died, he turned his back on that, turned down an assignment at the Pentagon and took his current position in Japan. His career suddenly didn’t seem to matter any more. He’d spent four years in Japan, career suicide at his rank, being away from Washington DC that long. Monica was now living in Santa Cruz, working in an art gallery, working at her painting.

When he put Tomoko’s artist biography in his pocket his fingers touched the note from Adams. Too late for almost everything now. But not too late to make a small gesture of thanks to a young woman on his staff who reminded him of Monica and the life he could have had. The proprietor handed Hallam the carefully wrapped package and he paid her sixty thousand yen, $600, and made his way down the narrow stair and out onto Motomachi street where he gave the two paintings to his driver.

“I’m going to walk to Yamashita Park. Pick me up there in twenty minutes.” He made his way down Motomachi Street, then crossed under the freeway bridge into the end of Yamashita Park. At the rose garden he stopped to admire the pale yellow blooms, then continued to the waterfront and stood looking out over Yokohama Bay.

David Kyle quietly joined him. “Counterintelligence is certain you’ve got a leak in your HQ. CID is working the issue now. The North Koreans operating in Japan use some pretty sophisticated pattern analysis software on U.S. military activities and on Japanese military. It’s surprising what can be deduced by just monitoring things like, say, fuel usage—the different kinds of aircraft fuel, jet, helicopter, fixed wing—that are supplied to the base. Compare it month to month. They know our equipment inventory, and the performance characteristics of each piece of equipment. They know our pattern of readiness and training exercises...”

“You’re saying that, based on the data you describe, the North Koreans can predict what kind of Operation we will be conducting before we start?”

“In many cases, yes. You can’t disguise a destroyer leaving the base,