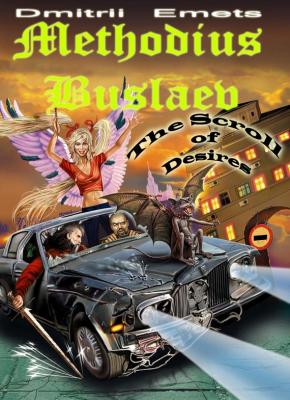

Methodius Buslaev. The Scroll of Desires. Дмитрий Емец

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Methodius Buslaev. The Scroll of Desires - Дмитрий Емец страница 5

himself through the grid, and continued to comb the city.

himself through the grid, and continued to comb the city.

“What are they doing here? Both agents and golden-winged? Why so many of them?” Daph asked with apprehension. “Searching. Both these and others. Only here, for some reason I believe more in the intrusiveness of plasticine villains,” Essiorh remarked sadly. “And the agents are not searching for me?” Daph asked just in case. Essiorh looked at her with compassion. “My good child! Are you at this again? As they once told us at briefing: the double repetition of a question indicates either depressive sluggishness or maniacal suspiciousness. Why would Gloom search for you when you’re already with Ares? No, they need something else,” he explained, with his tone showing that he was not about to explain what this something was.

“Fine, don’t tell. But can we play a little game of hot and cold?” Daph quickly asked. “You may. But I promise nothing,” emphasized Essiorh. “It goes without saying. Perhaps they need, by chance, that scroll, on which the impression of my wings would be found?” Daphne asked. “I’ve said too much,” the keeper growled. “What value does the scroll have? Why is it so necessary to Gloom? Essiorh, don’t be stubborn! Why hide from me what’s already known to all?” Daph quickly asked.

The guard-keeper was perceptibly embarrassed. The secret had turned out to be somewhat painfully transparent. Nevertheless, he continued to persist, “Time for me to go. We’ll still meet! Till we meet again! And don’t be offended! I can’t, I simply don’t have the right…” After nodding to her, Essiorh quickly jumped out of the arch. His prompt retreat resembled a flight. When, coming to her senses, Daph rushed after him, the street was empty. Only the wind was rocking the “No parking” sign suspended from a wire.

Pondering over the strange events of the day, Daph slowly wandered towards Bolshaya Dmitrovka. In a minute, not a single suspicion was left. Suspicion had strengthened little by little and changed into truth. The truth included the fact that her guard-keeper was a chronically unlucky wretch. “The most muddle-headed guard of Light simply by definition must have the most spontaneous keeper. Everything is logical. Don’t you think, huh?” she asked, turning to Depressiac. However, the cat was thinking about the dog across the street, sufficiently far from them. It was moving extremely insolently, holding its tail curled up, barking at cars, and ambiguously sniffing posts. Daph had to hold Depressiac tightly by the collar to end the discussion.

Chapter 2

Grabby Hands

Methodius kicked the chair in irritation. For a solid half-hour, he had been trying with mental magic push to light the candle standing on the chair some a metre away from him. However, in spite of so small a distance, the candle persistently ignored him. Then when Methodius got mad and attempted to put everything connected with this failure out of his head, the candle fell and in a flash became a puddle of wax. Moreover – what Buslaev discovered almost immediately – the metallic candlestick also melted together with the candle.

“I don’t know how to do anything. I’m a complete zero in magic. I have it either too weak or too strong. And I’m this future sovereign of Gloom? All of them are delirious! Better if Ares would teach me something besides slashing with swords!” Methodius grumbled, rewarding the chair with one more kick. The chair went off along the parquet for half a metre, wobbled several times in pensiveness, and changed its mind about falling.

Despite the fact that July was no longer simply looming on the horizon but literally dancing a lezginka on the very tip of the nose, Methodius, as before, was living in the Well of Wisdom high school, where annual exams had not yet ended. Vovva Skunso, having grown quiet, did not allow himself to play any tricks and was as polite as at a funeral.

The director Glumovich greeted Methodius every time he saw him in the hallway, even if they had met seven times in the day. At the same time, Buslaev constantly felt his sad, devoted, almost canine look. On rare occasions, Glumovich would approach Methodius and attempt to joke. The joke was always the same, “Well now, young man! Tell me your confusion of the day!” Glumovich said in a cheerful voice, but his lips trembled, and his forehead was porous and sweaty, like a wet orange. Every time Methodius had to exert himself in order not to absorb his fuzzy dirty raspberry-coloured aura accidentally. Nevertheless, Glumovich did not ignore exams, and it was difficult for Methodius, frequently letting his studies slide in previous grades. For the most part, it helped that even without him there were enough meatheads among Well’s noble students. Nature, having succumbed to a hernia in the parents, was making merry to the maximum in their children.

After throwing the damaged candlestick – it had not yet cooled and still burned the fingers – into the wastebasket, Methodius left the room and set off aimlessly wandering around the high school. The soft carpeting muffled his steps. Artificial palms were languidly basking in the rays of a florescent light. There were practically no students in the hallways. In the evenings, the parents dropped by to pick up the majority of them, and then on the other side of the gates by the entrance would line up a full exhibition of Lexus, Mercedes, Audi, and BMW. The Wisdom Wellers were usually more or less lacking in imagination. Waiting for their young, the padres of well-known last names winked slyly at each other by flashing signal lights and honking horns, greeting acquaintances.

Methodius slowly made his way along the empty high school corridors and, for something to do, studied photographs of earlier graduates, read the ads, the timetables, and in general everything in succession. He had long ago discovered in himself a special, almost pathological attachment to the printed word. In the subway, the children’s clinic, a store – everywhere boring for him, he fixed his eye on any letter and any text, even if it was a piece of yellowed newspaper once stuck under the wallpaper.

Here and now, he was interested in the amusing poster by the first aid station. On the poster was depicted a red-cheeked and red-nosed youth lying in bed with a thermometer, either projecting from under his armpit or like a stiletto piercing his heart. A white cloudlet with the following text was placed over the head of the youth, “Your health is our wealth. At the first sign of a head cold, which can be a symptom of the flu, immediately lie down in bed and stick to bed rest. Only this way will you be able to avoid complications.” Instead of an exclamation mark, the inscription was crowned with one additional thermometer, brother of the first, with the temperature standing still at 37.2.

Methodius instantly assessed the originality of the idea. He practically could always simulate a head cold. However, in half of the cases even a simulation was not necessary. “Eh, pity I didn’t know earlier! Must say I’ve ruined my health! How many school days spent in vain… But it won’t work with Ares, I fear! Can’t dodge the guards of Gloom with a head cold!” he thought and began to go down the stairs.

Soon Methodius was already on Bolshaya Dmitrovka. House № 13, surrounded by scaffolding as before, did not even evoke the curiosity of passers-by. A normal house, no more remarkable than other houses in the region. Methodius dived under the grid, looked sideways at the guarding runes flaring up with his approach, and, after pushing open the door, entered. The majority of agents and succubae had already given their reports and taken off. Only a vague smell of perfume, the stifling air, the floor spattered with spit, and heaps of parchments on the tables showed that there had been a crowd here recently.

Julitta looked irritated. The marble ashtray, which she had used the whole day to knock some sense into agents’ heads curing them of postscripts, was entirely covered in plasticine. Aspiring to cajole the witch who was losing her temper or at least to redirect the arrows, the agents told tales about each other. “Mistress, mistress! Tukhlomon is playing the fool again,” one started to whisper in a disgusting voice, covering his mouth with his hand. “Where?” “Hanging over there.” Julitta turned and made certain that the mocked Tukhlomon was in fact hanging on the entrance doors, with the handle of a dagger sticking out of his chest. His head was hanging like that of a chicken. Ink was dripping from his half-open mouth. This nightmarish spectacle would impress many, only not Julitta.