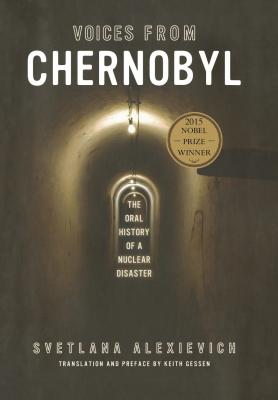

Voices from Chernobyl. Светлана Алексиевич

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Voices from Chernobyl - Светлана Алексиевич страница 4

night. On one side of the street there are buses, hundreds of buses, they’re already preparing the town for evacuation, and on the other side, hundreds of fire trucks. They came from all over. And the whole street covered in white foam. We’re walking on it, just cursing and crying. Over the radio they tell us they might evacuate the city for three to five days, take your warm clothes with you, you’ll be living in the forest. In tents. People were even glad—a camping trip! We’ll celebrate May Day like that, a break from routine. People got barbeques ready. They took their guitars with them, their radios. Only the women whose husbands had been at the reactor were crying.

night. On one side of the street there are buses, hundreds of buses, they’re already preparing the town for evacuation, and on the other side, hundreds of fire trucks. They came from all over. And the whole street covered in white foam. We’re walking on it, just cursing and crying. Over the radio they tell us they might evacuate the city for three to five days, take your warm clothes with you, you’ll be living in the forest. In tents. People were even glad—a camping trip! We’ll celebrate May Day like that, a break from routine. People got barbeques ready. They took their guitars with them, their radios. Only the women whose husbands had been at the reactor were crying.

I can’t remember the trip out to my parents’ village. It was like I woke up when I saw my mother. “Mama. Vasya’s in Moscow. They flew him out on a special plane!” But we finished planting the garden. [A week later the village was evacuated.] Who knew? Who knew that then? Later in the day I started throwing up. I was six months pregnant. I felt awful. That night I dreamed he was calling out to me in his sleep: “Lyusya! Lyusenka!” But after he died, he didn’t call out in my dreams anymore. Not once. [She starts crying.] I got up in the morning thinking I have to get to Moscow. By myself. My mother’s crying: “Where are you going, the way you are?” So I took my father with me. He went to the bank and took out all the money they had.

I can’t remember the trip. The trip just isn’t in my memory. In Moscow we asked the first police officer we saw, Where did they put the Chernobyl firemen, and he told us. We were surprised, too, everyone was scaring us that it was top secret. “Hospital number 6. At the Shchukinskaya stop.”

It was a special hospital, for radiology, and you couldn’t get in without a pass. I gave some money to the woman at the door, and she said, “Go ahead.” Then I had to ask someone else, beg. Finally I’m sitting in the office of the head radiologist, Angelina Vasilyevna Guskova. But I didn’t know that yet, what her name was, I didn’t remember anything. I just knew I had to see him. Right away she asked: “Do you have kids?”

What should I tell her? I can see already I need to hide that I’m pregnant. They won’t let me see him! It’s good I’m thin, you can’t really tell anything.

“Yes,” I say.

“How many?”

I’m thinking, “I need to tell her two. If it’s just one, she won’t let me in.”

“A boy and a girl.”

“So you don’t need to have anymore. All right, listen: his central nervous system is completely compromised, his skull is completely compromised.”

Okay, I’m thinking, so he’ll be a little fidgety.

“And listen: if you start crying, I’ll kick you out right away. No hugging or kissing. Don’t even get near him. You have half an hour.”

But I knew already that I wasn’t leaving. If I leave, then it’ll be with him. I swore to myself! I come in, they’re sitting on the bed, playing cards and laughing.

“Vasya!” they call out.

He turns around:

“Oh, well, now it’s over! Even here she found me!”

He looks so funny, he’s got pajamas on for a size 48, and he’s a size 52. The sleeves are too short, the pants are too short. But his face isn’t swollen anymore. They were given some sort of fluid.

I say, “Where’d you run off to?”

He wants to hug me.

The doctor won’t let him. “Sit, sit,” she says. “No hugging in here.”

We turned it into a joke somehow. And then everyone comes over, from the other rooms too, everyone from Pripyat. There were twenty-eight of them on the plane. What’s going on? How are things in town? I tell them they’ve begun evacuating everyone, the whole town is being cleared out for three or five days. None of the guys says anything, and then one of the women, there were two women, she was on duty at the factory the day of the accident, she starts crying.

“Oh God! My kids are there. What’s happening with them?”

I wanted to be with him alone, if only for a minute. The guys felt it, and each of them thought of some excuse, and they all went out into the hall. Then I hugged and kissed him. He moved away.

“Don’t sit near me. Get a chair.”

“That’s just silly,” I said, waving it away. “Did you see the explosion? Did you see what happened? You were the first ones there.”

“It was probably sabotage. Someone set it up. All the guys think so.”

That’s what people were saying then. That’s what they thought.

The next day, they were lying by themselves, each in his own room. They were banned from going in the hallway, from talking to each other. They knocked on the walls with their knuckles. Dash-dot, dash-dot. The doctors explained that everyone’s body reacts differently to radiation, and one person can handle what another can’t. They even measured the radiation of the walls where they had them. To the right, left, and the floor beneath. They moved out all the sick people from the floor below and the floor above. There was no one left in the place.

For three days I lived with my friends in Moscow. They kept saying: Take the pot, take the plate, take whatever you need. I made turkey soup for six. For six of our boys. Firemen. From the same shift. They were all on duty that night: Bashuk, Kibenok, Titenok, Pravik, Tischura. I went to the store and bought them toothpaste and toothbrushes and soap. They didn’t have any of that at the hospital. I bought them little towels. Looking back, I’m surprised by my friends: they were afraid, of course, how could they not be, there were rumors already, but still they kept saying: Take whatever you need, take it! How is he? How are they all? Will they live? Live. [She is silent.] I met a lot of good people then, I don’t remember all of them. I remember an old woman janitor, who taught me: “There are sicknesses that can’t be cured. You just have to sit and watch them.”

Early in the morning I go to the market, then to my friends’ place, where I make the soup. I have to grate everything and grind it. Someone said, “Bring me some apple juice.” So I come with six half-liter cans, always for six! I race to the hospital, then I sit there until evening. In the evening, I go back across the city. How much longer could I have kept that up? After three days they told me I could stay in the dorm for medical workers, it’s on hospital grounds. God, how wonderful!

“But there’s no kitchen. How am I going to cook?”

“You don’t need to cook anymore. They can’t digest the food.”

He started to change—every day I met a brand-new person. The burns started to come to the surface. In his mouth, on his tongue, his cheeks—at first there were little lesions, and then they grew. It came off in layers—as white film . . . the color of his face . . . his body . . . blue . . . red . . . gray-brown. And it’s all so very mine! It’s impossible to describe! It’s impossible to write down! And even to get over. The only thing that saved me was it happened so fast; there wasn’t any time to think, there wasn’t any time to cry.

I loved him! I had no idea how much! We’d just gotten married. We’re walking down the street—he’d grab my hands and whirl me around. And kiss me, kiss me. People are walking by and smiling.

It