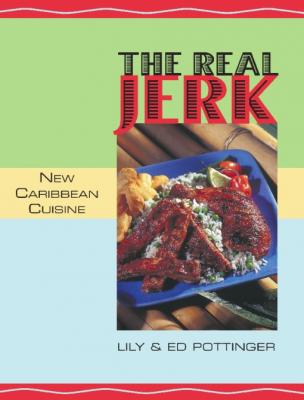

The Real Jerk. Lily Pottinger

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу The Real Jerk - Lily Pottinger страница 2

was the third child in a family of ten. I was an independent-minded and happy child, and I learned at an early age that I would probably have to work hard if I was going to be successful. By the age of six, I was already helping with washing, cooking, farming, and marketing for the family. With so many children in the house, space was at a premium. Privacy was rare. Still, my mother always told me that I was special; as a treat, she often left a piece of coconut toto or roasted breadfruit, wrapped in a towel, at the bottom of the dining-room cabinet, that was just for me.

was the third child in a family of ten. I was an independent-minded and happy child, and I learned at an early age that I would probably have to work hard if I was going to be successful. By the age of six, I was already helping with washing, cooking, farming, and marketing for the family. With so many children in the house, space was at a premium. Privacy was rare. Still, my mother always told me that I was special; as a treat, she often left a piece of coconut toto or roasted breadfruit, wrapped in a towel, at the bottom of the dining-room cabinet, that was just for me.

I have many happy memories of growing up in Jamaica: going to the river to catch crawfish; waking up early to fetch water for the family’s breakfast; picking pimentos during the summer on a large farm run by “Mr. Nick”; cooking on the beach with family and friends.

On Fridays, my father always brought home fresh fish, and my mom either fried it up or she’d make a big, simmering pot of fish soup. Mom made a different meal every day of the week, always using vegetables that were in season, and whatever meat and fish were available. Our family also raised chickens and pigs; what we didn’t sell or give away, we used for ourselves.

In addition to learning how to cook at home, I was inspired at school by my Home Economics teacher, Miss Tucker, who taught me how to be a creative cook. Along with home economics, I also specialized in business. This combination would help me a lot when Ed and I decided to open a restaurant.

ED:

I was born in Jamaica, but my family moved to England when I was five. Still, I have vivid childhood memories of the island, especially of waiting on the beach for my grandfather to return from fishing, all the while trying to run away from the snapping sand crabs around me. To this very day, I won’t eat crabs because of this!

My parents found England a difficult and quite hostile place to live. As a result, our home life was very important. Meals were special times, although I remember disliking Saturdays because that was soup day, and I didn’t like soup. But I could always look forward to the next day, Sunday, which meant a big meal — chicken, rice and peas, and fresh vegetables. One Sunday night, I ate so much and asked for more. My mother looked at me skeptically and asked if I could handle it. When I said “yes,” she marched me downstairs and made me eat a whole box of dry, saltine crackers.

After that, I learned to be happy with what was on my plate, and to not ask for more! However, it didn’t stop me from becoming a chicken thief. Where we lived, we shared the kitchen with two other families; we didn’t share meals, just the facilities. The preparation of Sunday dinner usually started the night before — chickens were fried and allowed to marinate in seasonings overnight. I soon learned to sneak into the kitchen during the night and raid the chicken pots, taking a leg here, a leg there. This went on for some time until people started to complain about their one-legged chickens. Eventually, I was found out, and my poor butt paid the price!

In the late 1970s, I returned to Jamaica — a young man eager to help my Uncle Barry with his import/export business. I promptly fell in love with the island all over again. I remember being surprised by the smiles on everyone’s faces; they had a joy for life, no matter what they were doing. I learned that the slow, easy pace of life is the best way to live.

I first saw Lily when she was walking home from school in St. Ann’s. For me, it was love at first sight, but I was too nervous to approach her, so I watched her walk home every day — for months! On her way home, she would always go down the street and go into a store near the gas station; I was sure she had a boyfriend there, but to my relief I learned her father had a sign-making studio there.

Opposite the gas station was the town’s police headquarters. The local cops would hang out in front, watching all the pretty girls go by. One day, one of the cops beckoned Lily to approach, and he whispered something to her. I watched with my heart in my mouth, but was ecstatic when Lily gave him a really nasty look and marched off. After that, I made sure that I got introduced to her. I was afraid someone else would win her heart before I did. I played it cool, because not only did I have to win her over, I had to win over her parents, four brothers, and five sisters.

General Patton had nothing on me. I would show up at opportune times and give her rides to the market or to school. Food played an important role in our courtship. I often bought homemade pudding or toto from the stands at St. Ann’s Bay and brought them to Lily. I was brilliant, and Lily became mine. It wasn’t long after we met that I opened up Little River Jerk, and Lily and I ran it. It was our first foray into the restaurant business.

LILY:

Well, Ed went to Canada in 1980 — his parents were already there — and he found work. I stayed behind in Jamaica, but Ed kept pestering me to follow him. In 1981, I decided to take a trip to Canada. Ed convinced me to stay and to marry him, and we’ve been together ever since. But I was homesick for Jamaica — being away from my family and in a new environment was very scary. In fact, I didn’t unpack my bags for over a year, until I felt I was truly ready to embrace my new life. Ed encouraged and supported me all the way.

ED:

I worked for General Motors, but after a few years I started to feel frustrated. I felt I needed to get away and work at something I really loved. At this time, Lily and I lived in Milton, about forty miles outside of Toronto. We’d just had our first son, Troy, and had purchased our first house. Still, I wasn’t happy. This led me to sit down one day and write down a list of all the things Lily and I were good at doing, and all the things we didn’t want to do. We kept referring to the wonderful experience we had running Little River Jerk back in Jamaica. I knew Lily was an excellent cook, and that I was good with people and also had some business smarts.

One day I left home and returned with a restaurant to our name. Lily didn’t believe me. Also, she’d just gotten a cashier’s job at the local supermarket and didn’t want to leave it. For two weeks I begged her to help me, reassuring her that it would work out in the end. She finally gave in, and we opened The Real Jerk. We started out with meager supplies — paper plates, plastic forks, Styrofoam cups. Our first day’s sales amounted to $20, enough to put gas in the car and go home. Every cent we made went into the restaurant. While those early years were hard, in truth we wouldn’t have wanted it any other way because we learned about the business from the inside out, and no one can ever take that away from us.

LILY:

In those early days of the restaurant, Ed would actually stand outside on the sidewalk offering free food and drinks to passersby, trying to entice them to try Jamaican cuisine. At that time, it was difficult to sell the concept of “jerk food” to Toronto; the only “jerk” people knew was the Steve Martin movie “The Jerk”! But Ed has always had a great rapport with people. He was able to bring in the customers, many of whom are customers to this very day. As time went by, people became more accustomed to the idea of Jamaican food. At the same time, Jamaica became a prime tourist destination for North Americans, and they returned home familiar with the food and the culture. Today in North America, it isn’t hard to find a Jamaican or Caribbean restaurant in large urban centers.

ED:

The best part of running any successful restaurant is not being really aware that it’s a success — I mean, it’s always so challenging that there is never time to pat ourselves on the back for a job well done. Maybe one day we can look back and say, “Wow, we actually did it,” but for us the most enjoyable thing is seeing the looks on people’s faces as they leave our restaurant. They’re happy and satisfied. When I opened the restaurant, I wanted to appeal to people’s five senses: the rich smell of the spices; the comforting sounds of reggae; the vibrant sight of the art murals on our walls; and the explosive