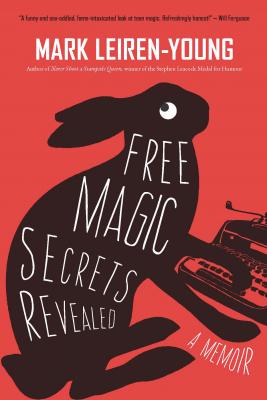

Free Magic Secrets Revealed. Mark Leiren-Young

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Free Magic Secrets Revealed - Mark Leiren-Young страница 2

the blade fell, right, man?”

the blade fell, right, man?”

Randy reached for his sore neck, rubbed it. “Yeah, it fell. But the head didn’t.”

“Musta stuck it in too hard. Maybe if we shave the Styrofoam a bit so it won’t fit so tight? Did the blood bag pop?”

“Does it look like the blood bag popped?”

Norman was thrown by Randy’s tone. Randy lived in a perpetual state of mellow. His mantra was, “Nooooo problemmm,” with the no stretched out to include anywhere between five and fifty extras o’s and at least a couple of bonus m’s at the end of every problem. But as a magician he knew that if the trick wasn’t working before opening night of his biggest show ever, he’d look like an idiot. “We already sold two hundred tickets,” said Randy. “At least two hundred people are gonna see this. Probably more like four hundred. We’re gonna sell out for sure.”

“Not if we cancel,” said Kyle. “We’re not ready.”

“I can fix it, man,” said Norman. “Just trust me.”

Randy picked up his Styrofoam head, leaned over to pop it back in the guillotine and the blood bag exploded, spraying a mix of ketchup and tomato soup all over the stage, the guillotine and Randy’s awesomely feathered hair. Randy went as pale as if all the blood was really his.

Norman was mortified.

I thought it was the coolest thing I’d ever seen.

2

Storming Troy

Like all great adventures, this one started with someone trying to get laid. King Menelaus didn’t go to Troy for the baklava. Actually, since all of us were teenagers running on high-octane hormones, it started with everyone trying to get laid.

I was seventeen and built to be beaten up. I had long, stringy brown hair that fell somewhere between Beatle and hippie, a stringy build—because I’d sprouted to almost 6'2" and still weighed as much as your average Girl Scout—teeth the orthodontist hadn’t tamed yet and wire-framed John Lennon glasses stuck to a nose and eyebrows that would have seemed a little much for Groucho Marx.

On days when my looks weren’t enough of a bully magnet, I also had a mouth with a death wish. Instead of responding to bullies like a sane, defenceless geek, I had the suicidal habit of responding to their taunts with my version of a Mad Magazine snappy answer to a stupid question, which led to my only useful physical skill. I could run pretty quickly—until I caught a whooping cough-like virus and could barely sprint a few feet without collapsing. Like I said, I was built to be beaten up.

For most of my high school life my dreams were ruled by Sarah Saperstein. So was my schedule. If she was in a class I wanted to take it. If I wasn’t in her class, I knew where her class was so I could accidentally walk by it before it started and after it was over.

I’d been in love with Sarah since I first saw her in the Jewish elementary school my mom banished me to when she split with my father, found religion, and decided to ruin my life by pulling me out of the public school all my friends were in and sending me to a place where all the other kids had studied Hebrew and Torah for four years. Overnight I went from being an A student who’d been given the option of skipping a grade to the dumb new kid who needed daily tutoring.

The idea was that I’d learn all about my heritage, conquer the Hebrew language, meet plenty of other Jewish kids and emerge from school with a deep connection to my religion.

I learned a little about my heritage, Hebrew conquered me, I met plenty of other Jewish kids and decided that if this was what Jewish kids were like I desperately wanted to be Japanese, like my neighbour, Ray Shimizu.

Pretty much the only thing I liked about Talmud Torah was Sarah. I had a crush on Sarah before I even considered liking girls. She was the only student, boy or girl, who didn’t seem to be afraid of the teachers—not even Mrs. Grimble, who could sense you chewing gum, and order you to spit it out, even with her back turned. And when I first noticed girls in the way most boys eventually do, Sarah was the first girl I noticed. But I didn’t truly fall in love with her until grade seven—the day we took a ferry to Victoria for a field trip to visit the provincial legislature and our boat was stopped midway to Vancouver Island and turned around because of a bomb scare.

This was 1975 and most kids had never heard of a bomb scare. But Jewish kids had—even the ones who didn’t go to private schools. This was around the time the Palestinian Liberation Organization was sending colourful envelopes to prominent North American Jews and, if you opened the special PLO packages, they had enough explosive power to kill you—though mostly they just blew off the lucky recipient’s hands or face. Because my mom’s father, my Zayda Ben, owned a chain of furniture stores that shared his last name, I’d never been allowed to touch the mail. So all the kids on our bus knew about bomb scares.

As everyone scrambled back to their seats, most of the girls were crying and most of the boys were too. They were all convinced we were going to die. Mrs. Grimble was screaming at everyone to calm down, but sounding more hysterical than reassuring. And as my twenty classmates sobbed or tried their best not to, Sarah came over, touched my hand and smiled shyly. It was the first time I’d seen her nervous. “Everyone’s scared,” she said.

“Yeah,” I said.

She squeezed into the empty seat next to me. “You should do something.”

I should do something?

I’d dreamed about rescuing Sarah from a terrorist attack on our school, and her being so grateful that she’d actually kiss me. On the lips and everything. I read a lot of Batman comics, every Sherlock Holmes adventure and far too many books on Houdini, so I’d memorized every exit to both buildings, including a few semi-secret ones—but how was I supposed to save the day in a bus on the bottom deck of a ferry?

The student teacher helping Mrs. Grimble chaperone us started to cry. The driver looked ready to bolt and abandon ship, in case the bomb was on our bus since, hey, we were the Jewish school and this was only three years after the massacre of the Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics. Everyone was convinced our ferry was going to blow up, and what good were lifeboats if the ferry exploded? And how were we supposed to get upstairs to the lifeboats when we were two levels below deck? That struck me as the biggest flaw in the “everyone go back down to your vehicles to await further instructions” plan.

“What can I do?” Sarah looked close to crying too.

“Tell stories,” she said. “You’re funny, make people laugh. Tell us stories and make us laugh and then it’ll all be okay.”

Before I could say anything, before I could even think anything, the boy in the seat in front of me turned around. It was Lenny Levitt, who beat me up at least twice a week to keep his fists in shape for hitting kids who could fight back. “Yeah,” he said. “Make us laugh.” It wasn’t a threat, more like a plea.

Everyone—everyone on the bus—must have heard him, because they all went quiet and turned to me. I’d just been drafted as the dance band on the Titanic. So I did the only thing I could. I laughed. Then I made fun of the field trip, said we’d never go down with the ship because Mrs. Grimble would get in way too much trouble with the principal and—I don’t know what I said, just that it must have been funny, because I remember Sarah’s smile. And her laughter. And everyone else’s laughter. And I remember a lot of kids—including the ones I wouldn’t have minded losing at sea, saying “Thank you” after the