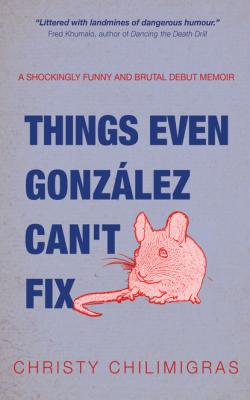

Things Even González Can't Fix. Christy Chilimigras

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Things Even González Can't Fix - Christy Chilimigras страница

n>

n>

‘Of all the ways you can kill yourself, using a bottle of tomato sauce is, I suspect, uncommon, says the narrator in this unusually frank account of a life of addiction. To which I might add: of all the ways to kill a person, pummelling him or her to death with knobkerries of dry humour is equally uncommon.

‘Writing about addiction is risky business. The writer risks being preachy and self-righteous, or fucking boring and judgmental. In this no-holds-barred tale, Chilimigras achieves an unusual feat of sharing some intimate slices of a life dangerously lived, without being melodramatic or over the top. It’s a controlled confession littered with landmines of dangerous humour, the kind that will get you kicked out of bed if you, like me, are one of those who do a lot of reading in it.

‘But when you’re finished laughing you can’t help but sit back and think. Very hard.’

– FRED KHUMALO, AUTHOR OF DANCING THE DEATH DRILL

Things Even González Can’t Fix

Christy Chilimigras

For Nicole,

For everything

For Nic,

Who always told me to just fucking write

For Jenny,

With the tiny handwriting

CHAPTER 1

Bandy Legs and Black Bob

We are a family of addicts. Of overachievers. Of failures that we have given birth to and nursed and smothered. We are generous. Gullible. We wear middle partings and all sound the same when we cry. We are selfish, disillusioned passers-of-the-buck-constantly-hungry-Greeks. We are racists and homophobes. We are liberal to the point of screaming matches and then we dissolve into a smug, quiet confidence. We thrive on chaos. We avoid conflict – and conflict resolution. We eat and eat and eat. And we run. We run away. To Cape Town. To our rooms. To a studio apartment. We choose shit romantic partners. We have spastic colons and thinning hair. We feel inadequate. We are vain. We hold tight to the belief that we are meant to struggle. We have a sense of entitlement. We are liars.

We. A family. That smothers and cries and eats and shits on love.

I was born bald in 1993. A bald, fat, Greek second baby to a gorgeous Greek woman, whom I call Old Lass, and a Greek man known for his charm and bandy legs, My Father. Their firstborn, my sister – known here as Protector & Soul – was a fair, scrawny baby, who had arrived two years earlier, in 1991. Her body skinny in the way that makes babies ‘beautiful’, skinny in the way that defies ‘cute’.

Old Lass met My Father when she was 23. Working in a small boutique at the time, she would armour herself in crisp white shirts boasting fine brooches and ‘funky shorts and boots’. Her exquisite, round face was framed by a black bob. Her new nose, gifted to her by her parents for her twenty-first birthday, somewhat disguised her glaringly Greek roots.

Introduced to My Father by her brother, Old Lass recalls the distinct lack of – as she so eloquently puts it – the gadoof. That feeling that it was ‘meant to be’. Rather, she saw My Father as the cultural plaster a young Greek woman puts over the wound of a lost Jewish love. She had adored Clive, his friends, the herring and kichel she’d dive into on Friday nights in his family home. She was patient with his parents, who seemed underwhelmed by her, as they were by everyone. She respected them, their culture and faith with a depth carved by her devotion to their son. However, when it came time to committing herself to their life, she thought of her own culture, her own traditions. Of Christmas. Of Greek Easters. Of dyeing boiled eggs red with her father the Thursday before Good Friday. Of tanned skin sizzling beneath a layer of olive oil under the Mykonos sun.

If she couldn’t convert herself into the circle that a round hole required, she would find another – a tanned, guilt-laden Greek square peg – with whom she would fit. Over time, she allowed herself to be taken by My Father’s charm. In the community to which my parents belonged, he was known as the life and soul of the party. For the Greek Zeibekiko dance, My Father would take the floor at gatherings, a pulsating wave of Greeks whirling around him. Whistling their whiskey-soaked breath in his direction from a knelt knee, plates would shatter around him and floors doused in liquor would be set alight. For this he was known. For this he was adored and revered, tears occasionally streaming from his calm eyes as he danced, so moved was he to dance to the notes of the bouzouki, amid the rosemary scent of roasted lamb. No one moved like him, and no one would forget him once he moved.

Only a breath into dating, on 30 June 1990, My Father and Old Lass were married. Protector & Soul arrived the next year, bundled into a gorgeous double-storey home in Sunninghill. The owner of a computer company (floppy discs were all the rage) – one of the first of its kind in Johannesburg – My Father spent his money on making this home just-so. An elaborate stairway led to finely furnished bedrooms. My mother, gifted a brand-new car tied in a pink bow as a Valentine’s Day gift, wanted for nothing, and it wasn’t long before she discovered that I was on the way. Old Lass had her life set out for her: a young, blonde, tantrum-throwing child at her side, and a bulging belly in which I was growing. My Father had his business, his friends – who all had their own businesses – and the cocaine that accompanied them on their daily comings and goings. ‘The businessman’s drug’, all the better to get them up and keep them busy.

My Father’s cocaine habit led him to a life spent chasing. It wasn’t long before someone handed him a pipe. In later years, he would tell me that he didn’t even know what crack was at that point. The pipe was just another rung on a rickety ladder to the sensational, heavenly sky to which cocaine beckoned him, an illusion that would eventually rob him of everything. Eventually the cells in his body belonged to another universe, the angels descending around him, comforting him, loving him, obsessing over him, fucking him. Soon he was no longer of this place, this place of Sunninghill homes and the pregnant belly of a wife with a round face and a perfect nose. He was living his new purpose, sweeping him higher-higher-higher than elaborate stairways or white powder trails had ever allowed him to go. There he was, My Father. And there he would remain, chasing that high, only to plummet downwards. Again and again for the rest of his life.

While I’ll never know how My Father truly felt the first time he put a crack pipe to his lips (my dedication to the craft of writing falls short of lunging myself into the deep end of filthy rocks for the sake of aptly portraying a scene), he told me about his first crack high when I was about eight years old and he, his life now depleted, had moved back into his childhood home, where Old Lass was not. We sat on the veranda, the sun glistening beyond the old, warped windows, begging me to run outside. To run away. To be a child rather than learn about crack. Be a child. Be a child.

Instead, I was told that the angels do exist, that he saw them. I was told that a body can feel as though it is made of gold, made by God. I was told that that one moment was worth a lifelong chase, one moment to live for, die for, exist for, never again to be obtained. I was told that that day, that first high, was ‘the best day of his life’.

‘What is cocaine, Daddy?’

‘What’s crack?’

‘Who gave it to you?’

‘Why did they give it to you?’