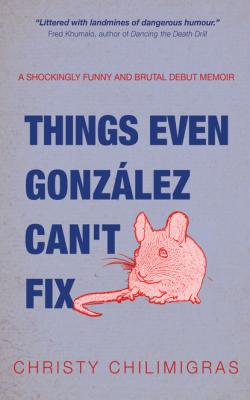

Things Even González Can't Fix. Christy Chilimigras

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Things Even González Can't Fix - Christy Chilimigras страница 4

he would occasionally make the great trek downstairs to visit his daughter and granddaughters, he would sit at the table and pick at the tuna salad or the leftover pizza, or whatever it was my mom has set in front of him. I would always greet him with ‘Hello, Pappouli,’ and he in turn would say, ‘Hello, my girl.’ We’d hug and his long palm would pat my back to the rhythm of his greeting. Hello. My. Girl. This man had no idea how strong he was and I’d always walk away from these hugs smiling at a man who believed he had little life left in him, but could potentially still pound the life out of another.

he would occasionally make the great trek downstairs to visit his daughter and granddaughters, he would sit at the table and pick at the tuna salad or the leftover pizza, or whatever it was my mom has set in front of him. I would always greet him with ‘Hello, Pappouli,’ and he in turn would say, ‘Hello, my girl.’ We’d hug and his long palm would pat my back to the rhythm of his greeting. Hello. My. Girl. This man had no idea how strong he was and I’d always walk away from these hugs smiling at a man who believed he had little life left in him, but could potentially still pound the life out of another.

My Pappou could tell stories. Long stories that were crafted with care and patience, with such intricate detailing that they could have been born from experiences of just yesterday. He’d tell stories that the family had heard countless times, that provoked sighs and slight smiles. Most of his tales would begin with ‘Thirty years ago’ and his pronunciation of the word ‘thirty’ was always one of my favourite things. The i of the ‘thirty’ would escape his lips in a high note, in a singsong manner that was drawn out and raised, and completely charming only because of the old mouth it came from. At an oval glass table that would go on to provide the frame for many a blanket fort in the years to come, the three generations would sit and eat and talk and sigh before he’d disappear once again up the dark stairwell, leaving his three girls rubbing his kind words, greetings and goodbyes, from our still-ringing backs.

In this, our new two-bedroomed home, Protector & Soul and I, along with our two best friends Brandon and Savannah, would put on Backstreet Boys concerts for our mothers. Five rand got you in. The four of us, a merry and mischievous gang dubbed ‘The Dragons’ would steal matches and set alight dry twigs under the washing line. We’d spend our hard-earned savings on BB guns from the flea market. We’d run through the black halls of the flats, at war with each other, at war with the world. It is here, in this home, that we’d convince Brandon that our Backstreet Boys concerts, while fabulous, were becoming tiresome and it was time we incorporated the Spice Girls into our repertoire. In this home, I would sit alone on the carpeted lounge floor, a single lit candle resting in front of my crossed legs, and screech along to Elton John’s ‘Candle in the Wind’. Then, at the end of the song, dramatically exhaling, blasting the flame into oblivion, before lighting it again and lambasting the neighbours’ ears once more. In this home, the poet, the romantic, the Dragon and the child in me thrive. I fall asleep every night praying to wake up to snow … in the middle of a South African summer. In this home, I name my first pets, two goldfish, Romeo and Juliet – only to wake a few weeks later to find them both floating, dead, in the bowl. Oh, the poetry of it all! For my two fish, Romeo and Juliet, to have pegged together, on the very same day! In this home I learn how to exhale, to play, and never treat my pets again as though they are Greek, thus avoiding over-feeding them to an untimely death.

At this point, while I am living my best life, My Father moves back to his childhood home with his mother, my YiaYia. Located in Rosebank, the low walls of this home barely conceal the stereotypes that keep the My Big Fat Greek Wedding franchise going. Old furniture preserved in mint condition with the help of plastic covers adorns the lounge and the dining room and the other dining room (one to use, one only to look at). Old biscuit tins filled with useful and useless things can be found in every room. Here, My Father and my YiaYia speak to each other in Greek bursts, and while I never understand a word of it, I know their conversations aren’t kind. My Father, still harbouring resentments from his early childhood, had proceeded to pack every issue he’d ever had with his mother neatly onto a shelf in his mind. Able to pick from the spines of his memory with feeling, eyes closed, he’d regale Protector & Soul and me with elaborate tales of all the ways in which she had failed him throughout his life. He would tell us, annunciating each heartbroken and heartbreaking syllable, how she’d never loved him as much as she did his sister, who was given a piano and a guitar and a car and he hadn’t. She hadn’t devoted as much of her attention or affection to him as she had with everyone else. She didn’t love my sister and I as much as she loved our cousins, who were born to the favoured sibling. He wasn’t good enough, and we weren’t good enough. ‘Look at how she brings your cousin chopped cucumber and tomato while he watches TV,’ he’d remind us as he swung his arm in the direction of my younger, blonde cousin with his big, lovely head staring contentedly at the television screen. ‘She doesn’t do that for you. Oh, and, Christy, even though you’re only six, she’s told the family back in Greece that you’re a poutana.’

‘What’s a “poutana”, Daddy?’

‘It means whore. Your grandmother tells everyone you’re a whore.’

My YiaYia, always clad in the same dresses, the pale pinks and greens of thin cotton lined with white frills that Johannesburg housewives buy for their domestic workers, would shuffle from room to room, her loose brown sandals exposing the chunky, plum veins resisting compression beneath her nude tights. Despite her legs betraying her, she is known for her flawless complexion. The skin on her face refuses to warp even while her sunken cheeks invite it to turn to waves. Framing her youthful face is her pale brown hair that dances with the grey but never lets it take the lead.

Having moved to South Africa at the age of 17 to start a new life for herself with my Pappou Number Two, she slowly somewhat mastered the English language. But even after a near-lifetime here, words spoken in anything other than her native language fall heavily from her lips like rocks she’s had to force out with a marshmallow tongue. Watching her through my young eyes in the mornings when I awoke in her home, I’d feel my frustration rise as she’d exhume a slice of white bread from within its packet before sliding it into an old, silver toaster. Once it abruptly popped up, only a few shades lighter than her houseboy, Paul, she’d carefully butter it. She’d slice it down the middle into two, oozing rectangles, and then with fluid movements, retrieve tin foil from the pantry, carefully wrap the toast, and lay it in a kitchen drawer next to where the cutlery slept. There the toast would sit untouched for two days, before she’d give in, tear it up, and toss it wildly into the air over the lawn, any number of birds waiting to be fattened up below. Having known what is was to be starving during her youth in Greece, she was adamant to always have food in her home, in her drawers, and, begrudgingly, finally in her neighbourhood pigeons. It didn’t matter how long she’d been in this country, she simply wasn’t of this country. Leaning in to me one day when I arrived at her front door with a childhood friend who’d come for a visit, she screamed in a whisper, ‘Chrysanthy, do you know your friend is a mavro?’

Me, responding in an actual whisper, ‘Yes, YiaYia, I know she’s black.’

In another of my earliest memories, I am in the back seat of My Father’s gold Toyota Corolla while my big sister, who at this point in her life is referred to as ‘Tiger’ by My Father, sits in the front seat with her tomboy-scabbed knees leaning dramatically to the left, away from the driver’s seat, distorting herself to the point that she looks ready to break. We are reversing out of the driveway. He has his arm slung over my sister’s seat to anchor his twisted body as he looks back, and says to me, ‘Mouse, I don’t care who you bring home. As long as he’s white. And if he’s Greek, that’s a bonus.’

I like to think that even then, at the age of seven or eight, I was certain of at least two things:

1 Whatever a mouse lacked, a tiger made up for.

2 My Father was absolutely full of shit.

I don’t remember when first we started spending every second weekend at My Father’s house. It was always just our condition. The way it was.

In playschool, I remember how every second Friday morning saw a shell of a Christy. Slinking into the classroom, I’d haul my black weekend bag along with me. The teacher would pop it, effortlessly, onto the top of a shelf where it would wait until My Father picked us up at the end of the day. There on the shelf it would watch and weigh on my mind. Heavy and horrendous and existing. The only solace during my childhood Fridays in playschool