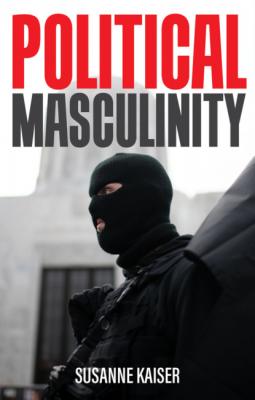

Political Masculinity. Susanne Kaiser

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Political Masculinity - Susanne Kaiser страница 5

work. This is a typically masculine gesture of disrespect that could have been taken straight out of a cowboy movie. Gallows were erected in front of the Capitol Building, and it was reported that they were set up for Pelosi. Whether the intention was really to hang the female politician or merely to stage a threat, we’ll never know. The message, however, was clear: women should be removed from political office, with force if necessary. These men were wildly determined to retake what they thought had been stolen from them: ‘their’ votes, ‘their’ country, ‘their’ privileges.

work. This is a typically masculine gesture of disrespect that could have been taken straight out of a cowboy movie. Gallows were erected in front of the Capitol Building, and it was reported that they were set up for Pelosi. Whether the intention was really to hang the female politician or merely to stage a threat, we’ll never know. The message, however, was clear: women should be removed from political office, with force if necessary. These men were wildly determined to retake what they thought had been stolen from them: ‘their’ votes, ‘their’ country, ‘their’ privileges.

Donald Trump was the first president to engage in identity politics with white masculinity, the first president of a Western nation whom an authoritarian backlash had helped to put into office. The so-called ‘storming’ of the Capitol was merely the climax of a development that we became used to seeing during his time in office – namely, the phenomenon of armed men rampaging around in public. This backlash is gendered; it is masculine, as I will show in this book. It is a reaction to the fact that women and other political minorities have become much more visible over the last twenty years, and have been fighting for rights and spaces like never before. The internet made this possible. Without the ‘digital revolution’ and the counter-public of social media, a movement such as #Metoo would have been unthinkable. This movement brought to light an unexpected and eruptive amount of potential and had a decisive influence on the patriarchal structures of the analogue world. It still, in fact, continues to influence the media, the economy, society and politics. Yet a formidable opposition has risen up against this shift towards more equal rights. By all available means, the actors involved in this authoritarian backlash seek to resist, throughout the West, the renegotiation and redistribution of privileges that many people have simply because they are male, white and hetero-cis.

This reactionary backlash movement existed before Trump – again, it helped to put him into the most influential political office in the world. Also, Trump’s political downfall was not brought about, for instance, by the fact that images of men terrorizing the public had become an almost daily occurrence during his time in office. Trump’s fall in popularity among certain sectors of the population was in fact brought about by the Covid pandemic. For he responded to this, too, with the same political programme of toxic masculinity, the heart of which consisted of lying, suppressing information and downplaying things. When Trump himself ultimately became infected with the virus, his political response was to dismiss the illness as being too weak for really strong men, and this message was heard loud and clear by his core supporters. An article in Mother Jones described how Trump staged this masculinity: still recovering and still contagious, Trump climbed up the stairs to the White House balcony, ripped off his mask in a pathetic gesture, and gave a salute to the presidential helicopter as it flew away in the direction of the Washington Monument. Later, a propaganda video of the scene was uploaded to Trump’s Twitter account. The video is set to an instrumental version of the song ‘Believe’, which appears on an album titled ‘Epic Male Songs’.1

A virus, however, cannot simply be gaslighted away; it will remain and spread unless measures are taken against it. The coronavirus demonstrated the limits of Trump’s politics of toxic masculinity. The political gestures of ‘strongmen’ such as Trump, Bolsonaro or Putin – and the male domination associated with these figures – have come under especially strong criticism during the pandemic and have increasingly been regarded as the negative foil to the leadership that women heads of state have shown during the crisis.2 Even the consulting firm McKinsey stated in a paper that the old leadership style was in a state of crisis. Today’s leaders, according to the authors of this paper, need to be able to work in teams, display deliberate calm and demonstrate empathy in order to manage new global challenges such as the pandemic.3

This has not been without consequences. Whereas the mainstream media praised women leadership, an additional discourse also emerged – a counter-discourse: in the semi-public spheres of social media, comment sections and internet forums, there has been an outpouring of frustration about women in power. When the British writer Matt Haig posted the picture of the seven women heads of state on Instagram, together with the remark ‘Time for women to lead the world’, this quickly led to comments such as: ‘Incel tsunami incoming’.4 With this reference to an incoming tsunami of incels, the commenter was simply anticipating what typically happens whenever something is posted about women who succeed in public domains, which are still regarded by many as domains for men: the post is mobbed, ridiculed, threatened, hated, and sometimes these threats are even translated into action, as demonstrated by the many attacks on women in recent years.

Women politicians such as Nancy Pelosi and the former German chancellor Angela Merkel, however, are not the only women who have been the target of verbal, and occasionally physical, attacks. Rather, all women who operate in the public sphere and have had success in (even presumably harmless) ‘masculine domains’ – such as women football commentators or women in ‘male’ film roles, for example – face the same risk. During the 2018 World Cup, every game with a woman announcer was followed by a shitstorm on social media devoted to denigrating the women commentators in question.5 And, however silly this might sound, a great many men regard the masculinity of Ghostbusters as sacrosanct. When the trailer for a female version appeared in 2016, it was ripped apart in YouTube’s comment section as stupid and unworthy – not, for instance, because it’s a trashy ghost story, but rather because the main roles were played by women. The clip was watched more than 46 million times; it was ‘disliked’ more than a million times, and it prompted more than 260,000 largely disparaging or even openly misogynistic comments.6 By way of comparison, the trailer for one of the most successful films of all time, Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker, from 2019, attracted fewer clicks (44 million), received only 114,000 dislikes, and instigated just 90,000 comments, which are not discriminatory.7

The reactionary counter-discourse has emerged from a field of tension. On the one hand, male privileges persist today and are deeply and structurally embedded in our society. For centuries, masculinity has been the norm around which everything has been oriented, and beneath which everything is expected to be subordinated. In her book Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men, Caroline Criado Perez has recently demonstrated how deeply these androcentric structures in fact reach.8 In so many areas of life, women are still disadvantaged, despite the fact that they have long been on supposedly equal footing with men in the eyes of the law. The needs of men remain the standard by which everything is still measured, whether in daily life, at work, in product designs, in medicine or in the public sphere. Regardless of whether we have in mind crash-test dummies, automatic doors, workloads, tools, devices, safety equipment, bulletproof vests, seatbelts, medications, pacemakers or the temperatures in climate-controlled buildings, man is still the measure of all things.

On the other hand, however – and like never before – women and other political minorities in Western societies have been calling into question this norm and the related privileges associated with white, male, hetero-cis domination. Ethically, normatively and discursively, the patriarchy has increasingly come under pressure. The prevailing social consensus is that equal rights are a desirable goal, and this view also sets the tone in the liberal progressive media.

This tension between the factual reality of the patriarchy and its discursive downfall is an essential reason why, in recent years, we have experienced a glut of denigrating and often hateful rhetoric against women. The polemics against equal rights – in the form of men’s forums, comment sections, or on social media – are only a small part of a large movement whose agitations against women and women’s rights can be observed in many social and political spheres. And, as chaotic as the storming of the Capitol Building may have seemed, scenes like this in public space are in fact well orchestrated. From Canada to New Zealand, from Brazil to Poland, there is a well-organized network of misogynistic, extreme right-wing actors who operate globally, as I will show with many examples in this book. Before the proponents of this movement take to the streets, there is first a verbal smear campaign; before women are treated with actual violence in the material world, violence-glorifying content is first shared on the internet. There is an online–offline continuum at work, and it is clear to