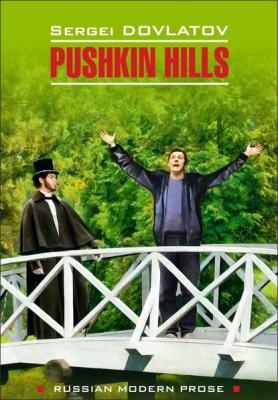

Pushkin Hills / Заповедник. Книга для чтения на английском языке. Сергей Довлатов

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Pushkin Hills / Заповедник. Книга для чтения на английском языке - Сергей Довлатов страница 4

aspect in isolation.

aspect in isolation.

A man has been writing stories for twenty years. He is convinced that he picked up the pen for a reason. People he trusts are ready to attest to this.

You are not being published. You are not welcomed into their circles, into their band of bandits. But is that really what you dreamt of when you mumbled your first lines?

You want justice? Relax, that fruit doesn’t grow here. A few shining truths were supposed to change the world for the better, but what really happened?

You have a dozen readers and you should pray to God for fewer…

You don’t make any money – now that’s not good. Money is freedom, space, caprice. Money makes poverty bearable.

You must learn to make money without being a hypocrite. Go work as a stevedore and do your writing at night. Mandelstam[21] said that people will preserve what they need. So write.

You have some ability – you might not have. Write. Create a masterpiece. Give your reader a revelation. One single living person. That’s the goal of a lifetime.

And what if you don’t succeed? Well, you’ve said it yourself – morally, a failed attempt is even more noble, if only because it is unrewarded.

Write, since you picked up the pen, and bear this burden. The heavier it is, the easier…

You are weighed down by debts? Name someone who hasn’t been! Don’t let it upset you. After all, it’s the only bond that really connects you to other people.

Looking around, do you see ruins? That was to be expected. He who lives in the world of words does not get along with things.

You envy anyone who calls himself a writer, anyone who can present a legal document with proof of that fact.

But let’s look at what your contemporaries have written. You’ve stumbled on the following in the writer Volin’s work[22]:

“It became comprehensibly clear to me…”

And on the same page:

“With incomprehensible clarity Kim felt…”

A word is turned upside down. Its contents fall out. Or rather, it turns out it didn’t have any. Words piled intangibly, like the shadow of an empty bottle.

But that’s not the point! I’m so tired of your constant manipulation!

Life is impossible. You must either live or write. Either the word or business. But the word is your business. And you detest all Business with a capital B. It is surrounded by empty, dead space. It destroys everything that interferes with your business. It destroys hopes, dreams and memories. It is ruled by contemptible, incontrovertible and unequivocal materialism.

And again – that’s not the point!

What have you done to your wife? She was trusting, flirtatious and fun-loving. You made her jealous, suspicious and neurotic. Her persistent response: “What do you mean by that?” is a monument to your cunning…

Your outrageousness borders on the extraordinary. Do you remember when you came home around four o’clock in the morning and began undoing your shoelaces? Your wife woke up and groaned:

“Dear God, where are you off to at this hour?!”

“You’re right, you’re right, it’s too early,” you mumbled, undressed quickly and lay down.

Oh, what more is there to say?

Morning. Footsteps muffled by the crimson runner. Abrupt sputtering of the loudspeaker. The splash of water next door. Trucks outside. The startling call of a rooster somewhere in the distance.

In my childhood the sound of summer was marked by the whistling of steam engines. Country dachas… The smell of burnt coal and hot sand… Table tennis under the trees. The taut and clear snap of the ball. Dancing on the veranda (your older cousin trusted you to wind the gramophone). Gleb Romanov. Ruzhena Sikora. “This song for two soldi, this song for two pennies…”, ‘I Daydreamt of You in Bucharest…’[23]

The beach burnt by the sun. The rugged sedge. Long bathing trunks and elastic marks on your calves. Sand in your shoes.

Someone knocked on the door:

“Telephone!”

“That must be a mistake,” I said.

“Are you Alikhanov?”

I was shown to the housekeeper’s room. I picked up the receiver.

“Were you sleeping?” asked Galina.

I protested emphatically.

I noticed that people respond to this question with excessive fervour. Ask a person, “Do you go on benders[24]?” and he will calmly say, “No.” Or, perhaps, agree readily. But ask, “Were you sleeping?” and the majority will be upset as if insulted. As if they were implicated in a crime.

“I’ve made arrangements for a room.”

“Well, thank you.”

“It’s in a village called Sosnovo. Five minutes away from the tourist centre. And it has a private entrance.”

“That’s key.”

“Although the landlord drinks…”

“Yet another bonus.”

“Remember his name – Sorokin. Mikhail Ivanych… Walk through the tourist centre, along the ravine. You’ll be able to see the village from the hill. Fourth house. Or maybe the fifth. I’m sure you’ll find it. There’s a dump next to it.”

“Thank you, darling.”

Her tone changed abruptly.

“Darling?! You’re killing me. Darling. Honestly. So, he’s found himself a darling.”

Later on, I’d often be astonished by Galina’s sudden transformations. Lively involvement, kindness and sincerity gave way to shrill inflections of offended virtue. Her normal voice was replaced by a piercing provincial dialect.

“And don’t get any ideas!”

“Ideas – never. And once again – thank you…”

I headed to the tourist centre. This time it was full of people. Colourful automobiles were parked all around. Tourists in sun hats ambled in groups and on their own. A line had formed by the newspaper kiosk. The clatter of crockery and the screeching of metallic stools came through the wide-open windows of the cafeteria. A few well-fed mutts romped around in the middle of it all.

A picture of Pushkin greeted me everywhere I looked. Even near the mysterious little brick booth with the “Inflammable!” sign. The similarity was confined to the sideburns. Their amplitude varied indiscriminately. I noticed long ago that our artists favour certain objects that place no restriction on the scale or the imagination.

Mandelstam: Osip Mandelstam (1891–1938), Russian poet and essayist.

the writer Volin’s work: Probably Vladimir Volin (192498), writer and journalist who worked for a variety of Soviet magazines and journals.

Gleb Romanov, in Bucharest: Gleb Romanov (1920-67) was a popular actor and performer. Ruzhena Sikora (19182006) was a well-known Soviet singer of Czech origin. “This song for two

to go on a bender – уйти в запой