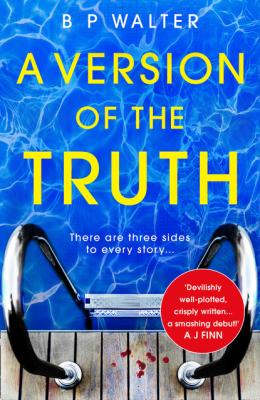

A Version of the Truth. B P Walter

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу A Version of the Truth - B P Walter страница 6

coming!’ I shout back, trying to sound normal. Walking the short distance across the landing and down the stairs feels like I’m doing the last leg of a double marathon. I keep thinking I’m going to stumble and fall, but I hold on tight to the handrail and press on, determined. Determined not to believe the worst. Determined to shake the horrible feeling that something, finally, is threatening to shake the foundations of what we’ve built together. Determined to remain convinced he’ll explain everything, clearly and calmly, and all of this will go away. He’ll tell me the documents are something he accidentally got sent. Or important documents from his work that somehow ended up in the wrong folder. He’ll tell me how sorry he is that I had to worry about all this, especially at Christmas, and that I should put it all out of my mind and forget about it. I think of the relief I will feel when I hear those words.

coming!’ I shout back, trying to sound normal. Walking the short distance across the landing and down the stairs feels like I’m doing the last leg of a double marathon. I keep thinking I’m going to stumble and fall, but I hold on tight to the handrail and press on, determined. Determined not to believe the worst. Determined to shake the horrible feeling that something, finally, is threatening to shake the foundations of what we’ve built together. Determined to remain convinced he’ll explain everything, clearly and calmly, and all of this will go away. He’ll tell me the documents are something he accidentally got sent. Or important documents from his work that somehow ended up in the wrong folder. He’ll tell me how sorry he is that I had to worry about all this, especially at Christmas, and that I should put it all out of my mind and forget about it. I think of the relief I will feel when I hear those words.

Holly

Oxford, 1990

Oxford wasn’t for the likes of me, that’s what my father told me. He even repeated it as we were driving up towards the halls of residence. ‘We’re simple folk, you, me and your mum. Don’t forget these types have had it all. Don’t forget you’re different.’

I hopped out of the car first to speak to one of the stewards showing us where to park, asking the best way to negotiate the trailer through the tiny lane that snaked around Hawksmith Hall – my new home away from home. I’d been worried Dad would bring the trailer ever since he and Mum had started working out the logistics of taking me and my stuff up there on my first day. I knew he had a customer in a village just outside of Oxford – I’d almost missed my interview when he’d insisted on having his ‘business meeting’ first. Business meeting. More like ripping off an overenthusiastic collector. He had been working in the antiques business for about ten years, ever since the chemical factory had made him redundant. Old furniture, great big chests, mirrors, tables, all sorts really, anything you could use to furnish a home. He’d bought loads of books on the subject of antiques dealing. I’d been surprised there were that many, but apparently it was an area of interest for a lot of ‘retired people’. That was how he always put it: ‘retired’. Never ‘laid off’ or ‘redundant’.

Once we finally got ourselves sorted in the car park and the trailer was safely out of the way next to a wall of bushes, I ventured in and up the stairs, carrying a bag in one hand and my key in the other. My parents followed behind me, lugging the heavier bags. I’d told them I would come back to get them but they were as keen as I was to see where I’d be staying. ‘Very nice,’ my mum kept saying as we climbed the stone steps to the first floor. ‘Thank God you got that grant, Holly,’ she said in a whisper, which still carried audibly through the corridor. ‘It’s good you get to experience a place like this.’

‘Mum, please,’ I murmured. I didn’t mind people knowing I hadn’t been born with a silver spoon in my mouth, but it wasn’t something I wanted broadcasting as I walked through the door. Besides, there must be a lot of people here who didn’t come from privilege. This was the 1990s. Class was something we were leaving behind, wasn’t it?

The room was spacious, if not exactly homely. It looked rather grand, as if someone had converted part of a cathedral into a living space. The bed was a single, but more than adequate, and the floor had a large, deep-red rug in the centre. In the far corner were a desk and chair. I placed the bag I was holding on the bed and turned to my parents, taking in their reactions.

‘Very nice,’ Mum kept saying. ‘Very, very nice.’

‘You’ll be comfy here,’ said Dad, as if he’d parked me in a B&B. I think he was rather overwhelmed by the whole thing. In fact, I knew he was by the way he kept looking around and then quickly focusing on the floor, as if someone might notice him staring.

‘Can you guys stay here while I get the last few bags from the car?’ I said, slightly worried about leaving them. They might wander.

‘Of course, love, but we can come and help.’

‘No, Dad, it’s fine,’ I said, backing out of the door. ‘I’ll be back in a minute.’

I left before they could protest any further and walked the short distance back to the car. When I got there, I saw three girls standing by it, looking at something. As I got closer, I could see they were peering over into the car and laughing. I felt rather nervous as I approached, worried they’d try to speak to me, and when they saw me they took a step back. One of them looked a bit embarrassed, as if she’d been caught out, but the other two had looks on their faces that weren’t quite as nice.

‘Is this yours?’ one of them asked.

I eyed her suspiciously and replied that, yes, it was and asked if there was a problem. One of the other girls laughed, while the one I was speaking to just looked back at the old car, partly splashed with mud, the boot slightly dented from a minor back-end collision a year ago. I saw her eyes flick to the trailer, the old, ripped covering my dad used to cover up whatever was being transported bundled in the back, and then they fell back on me. She didn’t say anything. Just looked me up and down one last time and walked away, the other two following her like sheep. I waited until they’d disappeared out of sight around the side of the building before opening the car. There were more bags left than I’d realised and I tutted to myself at the thought of having to come back again for the rest. I didn’t really want to admit how they’d made me feel in our half a minute of meeting, but the sense of unease I’d had ever since getting the letter of acceptance from Oxford had suddenly become a lot stronger.

Back in my room, my parents helped me unpack for a bit, but I could tell Dad was itching to head off to meet his antiques contact. Mum, on the other hand, had settled herself on the bed and was unballing my socks from the bag and folding them neatly. At one point a girl knocked on our door asking if we knew the way to somewhere called Gallery Heights as she’d been looking around for ages. I tried to answer quickly, but my dad got in first: ‘We’re not locals, love. Never been here in my life. Apart from when I was a teenager. Not at the university – God, no – but as a lad when I was working for the railways …’

‘Dad.’ I cut in to rescue the girl, who was looking at him as if he were a strange animal in a zoo. I turned to face her. ‘I’m sorry, I’ve only just arrived and I don’t really know the way around myself.’

The girl nodded. ‘Oh, no problem,’ she said stiffly, then vanished from the doorway.

After another awkward twenty minutes of unpacking and questions from Mum on where I’d be keeping my knickers and ‘lady things’, we all traipsed back down to the car to get my last two bags.

‘Full of books, I bet,’ Dad said, shaking his head, lifting one of the bags out. ‘Well, I suppose you proved they had some worth, getting into this place. Never understand how you have the patience, love.’ I’d heard this speech more times than I wanted to remember and didn’t respond now. All through my childhood I’d been treated like some weird outcast, as if spending one’s weekends buried in a novel were a sign of derangement. Mum frequently made comments about how I’d never really made an effort with ‘more traditional things’, like make-up and nice clothes. When I’d told her there wasn’t much point, as we couldn’t afford expensive make-up and nice clothes, she’d told me I was ungrateful. Maybe I was. Or maybe I was just angry at not being allowed the thing I alone enjoyed without being made to feel bad about it whenever someone else came into the room.

‘You guys can get going. I’m fine from here, honestly.’

Mum