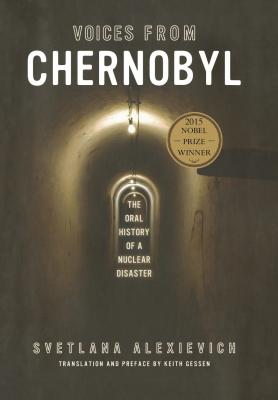

Voices from Chernobyl. Светлана Алексиевич

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Voices from Chernobyl - Светлана Алексиевич страница 10

going to die, we’re going to die. By the year 2000, there won’t be any Belarussians left.” My daughter was six years old. I’m putting her to bed, and she whispers in my ear: “Daddy, I want to live, I’m still little.” And I had thought she didn’t understand anything.

going to die, we’re going to die. By the year 2000, there won’t be any Belarussians left.” My daughter was six years old. I’m putting her to bed, and she whispers in my ear: “Daddy, I want to live, I’m still little.” And I had thought she didn’t understand anything.

Can you picture seven little girls shaved bald in one room? There were seven of them in the hospital room . . . But enough! That’s it! When I talk about it, I have this feeling, my heart tells me—you’re betraying them. Because I need to describe it like I’m a stranger. My wife came home from the hospital. She couldn’t take it. “It’d be better for her to die than to suffer like this. Or for me to die, so that I don’t have to watch anymore.” No, enough! That’s it! I’m not in any condition. No.

We put her on the door . . . on the door that my father lay on. Until they brought a little coffin. It was small, like the box for a large doll.

I want to bear witness: my daughter died from Chernobyl. And they want us to forget about it.

Nikolai Fomich Kalugin, father

MONOLOGUES BY THOSE WHO RETURNED

The village of Bely Bereg, in the Narovlyansk region, in the Gomel oblast.

Speaking: Anna Pavlovna Artyushenko, Eva Adamovna Artyushenko, Vasily Nikolaevich Artyushenko, Sofya Nikolaevna Moroz, Nadezhda Borisovna Nikolaenko, Aleksandr Fedorosvich Nikolaenko, Mikhail Martynovich Lis.

“And we lived through everything, survived everything . . .”

“Oh, I don’t even want to remember it. It’s scary. They chased us out, the soldiers chased us. The big military machines rolled in. The all-terrain ones. One old man—he was already on the ground. Dying. Where was he going to go? ‘I’ll just get up,’ he was crying, ‘and walk to the cemetery. I’ll do it myself.’ What’d they pay us for our homes? What? Look at how pretty it is here! Who’s going to pay us for this beauty? It’s a resort zone!”

“Planes, helicopters—there was so much noise. The trucks with trailers. Soldiers. Well, I thought, the war’s begun. With the Chinese or the Americans.”

“My husband came home from the kolkhoz meeting, he says, ‘Tomorrow we get evacuated.’ And I say: ‘What about the potatoes? We didn’t dig them out yet. We didn’t get a chance.’ Our neighbor knocks on the door, and we sit down for a drink. We have a drink and they start cursing the kolkhoz chairman. ‘We’re not going, period. We lived through the war, now it’s radiation.’ Even if we have to bury ourselves, we’re not going!”

“At first we thought, we’re all going to die in two to three months. That’s what they told us. They propagandized us. Scared us. Thank God—we’re alive.”

“Thank God! Thank God!”

“No one knows what’s in the other world. It’s better here. More familiar.”

“We were leaving—I took some earth from my mother’s grave, put it in a little sack. Got down on my knees: ‘Forgive us for leaving you.’ I went there at night and I wasn’t scared. People were writing their names on the houses. On the wood. On the fences. On the asphalt.”

“The soldiers killed the dogs. Just shot them. Bakh-bakh! After that I can’t listen to something that’s alive and screaming.”

“I was a brigade leader at the kolkhoz. Forty-five years old. I felt sorry for people. We took our deer to Moscow for an exhibition, the kolkhoz sent us. We brought a pin back and a red certificate. People spoke to me with respect. ‘Vasily Nikolaevich. Nikoleavich.’ And who am I here? Just an old man in a little house. I’ll die here, the women will bring me water, they’ll heat the house. I felt sorry for people. I saw women walking from the fields at night singing, and I knew they wouldn’t get anything. Just some sticks on payday. But they’re singing . . .”

“Even if it’s poisoned with radiation, it’s still my home. There’s no place else they need us. Even a bird loves its nest . . .”

“I’ll say more: I lived at my son’s on the seventh floor. I’d come up to the window, look down, and cross myself. I thought I heard a horse. A rooster. I felt terrible. Sometimes I’d dream about my yard: I’d tie the cow up and milk it and milk it. I wake up. I don’t want to get up. I’m still there. Sometimes I’m here, sometimes there.”

“During the day we lived in the new place, and at night we lived at home—in our dreams.”

“The nights are very long here in the winter. We’ll sit, sometimes, and count: who’s died?”

“My husband was in bed for two months. He didn’t say anything, didn’t answer me. He was mad. I’d walk around the yard, come back: ‘Old man, how are you?’ He looks up at my voice, and that’s already better. As long as he was in the house. When a person’s dying, you can’t cry. You’ll interrupt his dying, he’ll have to keep struggling. I took a candle from the closet and put it in his hand. He took it and he was breathing. I can see his eyes are dull. I didn’t cry. I asked for just one thing: ‘Say hello to our daughter and to my dear mother.’ I prayed that we’d go together. Some gods would have done it, but He didn’t let me die. I’m alive . . .”

“Girls! Don’t cry. We were always on the front lines. We were Stakhanovites. We lived through Stalin, through the war! If I didn’t laugh and comfort myself, I’d have hanged myself long ago.”

“My mother taught me once—you take an icon and turn it upside-down, so that it hangs like that three days. No matter where you are, you’ll always come home. I had two cows and two calves, five pigs, geese, chicken. A dog. I’ll take my head in my hands and just walk around the yard. And apples, so many apples! Everything’s gone, all of it, like that, gone!”

“I washed the house, bleached the stove. You need to leave some bread on the table and some salt, a little plate and three spoons. As many spoons as there are souls in the house. All so we could come back.”

“And the chickens had black cockscombs, not red ones, because of the radiation. And you couldn’t make cheese. We lived a month without cheese and cottage cheese. The milk didn’t go sour—it curdled into powder, white powder. Because of the radiation.”

“I had that radiation in my garden. The whole garden went white, white as white can be, like it was covered with something. Chunks of something. I thought maybe someone brought it from the forest.”

“We didn’t want to leave. The men were all drunk, they were throwing themselves under cars. The big Party bosses were walking to all the houses and begging people to go. Orders: ‘Don’t take your belongings!’ ”

“The cattle hadn’t had water in three days. No feed. That’s it! A reporter came from the paper. The drunken milkmaids almost killed him.”

“The chief is walking around my house with the soldiers. Trying to scare me: ‘Come out or we’ll burn it down! Boys! Give me the gas can.’ I was running around—grabbing a blanket, grabbing a pillow.”

“During the war you hear the guns all night hammering, rattling. We dug a hole in the forest. They’d bomb and bomb. Burned everything—not just the houses, but the gardens, the cherry trees, everything. Just as long as there’s no war. That’s what I’m scared of.”

“They