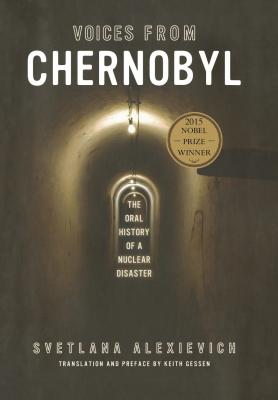

Voices from Chernobyl. Светлана Алексиевич

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Voices from Chernobyl - Светлана Алексиевич страница 13

we haven’t even planted the garden.”

we haven’t even planted the garden.”

If everyone was smart, then who’d be the dumb ones? It’s on fire—so it’s on fire. A fire is temporary, no one was scared of it then. They didn’t know about the atom. I swear on the Cross! And we were living next door to the nuclear plant, thirty kilometers as the bird flies, forty on the highway. We were satisfied. You could buy a ticket and go there—they had everything, like in Moscow. Cheap salami, and always meat in the stores. Whatever you want. Those were good times!

Sometimes I turn on the radio. They scare us and scare us with the radiation. But our lives have gotten better since the radiation came. I swear! Look around: they brought oranges, three kinds of salami, whatever you want. And to the village! My grandchildren have been all over the world. The littlest just came back from France, that’s where Napoleon attacked from once—“Grandma, I saw a pineapple!” My nephew, her brother, they took him to Berlin for the doctors. That’s where Hitler started from on his tanks. It’s a new world. Everything’s different. Is that the radiation’s fault, or what?

What’s it like, radiation? Maybe they show it in the movies? Have you seen it? Is it white, or what? What color is it? Some people say it has no color and no smell, and other people say that it’s black. Like earth. But if it’s colorless, then it’s like God. God is everywhere, but you can’t see Him. They scare us! The apples are hanging in the garden, the leaves are on the trees, the potatoes are in the fields. I don’t think there was any Chernobyl, they made it up. They tricked people. My sister left with her husband. Not far from here, twenty kilometers. They lived there two months, and the neighbor comes running: “Your cow sent radiation to my cow! She’s falling down.” “How’d she send it?” “Through the air, that’s how, like dust. It flies.” Just fairy tales! Stories and more stories.

But here’s what did happen. My grandfather kept bees, five nests of them. They didn’t come out for two days, not a single one. They just stayed in their nests. They were waiting. My grandfather didn’t know about the explosion, he was running all over the yard: what is this? What’s going on? Something’s happened to nature. And their system, as our neighbor told us, he’s a teacher, it’s better than ours, better tuned, because they heard it right away. The radio wasn’t saying anything, and the papers weren’t either, but the bees knew. They came out on the third day. Now, wasps—we had wasps, we had a wasps’ nest above our porch, no one touched it, and then that morning they weren’t there anymore—not dead, not alive. They came back six years later. Radiation: it scares people and it scares animals. And birds. And the trees are scared, too, but they’re quiet. They won’t say anything. It’s one big catastrophe, for everyone. But the Colorado beetles are out and about, just as they always were, eating our potatoes, they scarf it down to the leaf, they’re used to poison. Just like us.

But if I think about it—in every house, someone’s died. On that street, on the other side of the river—all the women are without men, there aren’t any men, all the men are dead. On my street, my grandfather’s still alive, and there’s one more. God takes the men earlier. Why? No one can tell us. But if you think about it—if only the men were left, without any of us, that wouldn’t be any good either. They drink, oh do they drink! From sadness. And all our women are empty, their female parts are ruined in one in three of them, they say. In the old and the young, too. Not all of them managed to give birth in time. If I think about it—it just went by, like it never was.

What else will I say? You have to live. That’s all.

And also this. Before, we churned our butter ourselves, our cream, made cottage cheese, regular cheese. We boiled milk dough. Do they eat that in town? You pour water on some flour and mix it in, you get these torn bits of dough, then you put these in the pot with some boiled water. You boil that and pour in some milk. My mom showed it to me and she’d say: “And you, children, will learn this. I learned it from my mother.” We drank juice from birch and maple trees. We steamed beans on the stove. We made sugared cranberries. And during the war we gathered stinging-nettle and goose-foot. We got fat from hunger, but we didn’t die. There were berries in the forest, and mushrooms. But now that’s all gone. I always thought that what was boiling in your pot would never change, but it’s not like that. You can’t have the milk, and the beans either. They don’t let you eat the mushrooms or the berries. They say you have to put the meat in water for three hours. And that you have to pour off the water twice from the potatoes when you’re boiling them. Well, you can’t wrestle with God. You have to live. They scare us, that even our water you can’t drink. But how can you do without water? Every person has water inside her. There’s no one without water. Even rocks have water in them. So, maybe, water is eternal? All life comes from water. Who can you ask? No one will say. People pray to God, but they don’t ask him. You just have to live.

Anna Petrovna Badaeva, re-settler

MONOLOGUE ABOUT A SONG WITHOUT WORDS

I’ll get down on my knees to beg you—please, find our Anna Sushko. She lived in our village. In Kozhushki. Her name is Anna Sushko. I’ll tell you how she looked, and you’ll type it up. She has a hump, and she was mute from birth. She lived by herself. She was sixty. During the time of the transfer they put her in an ambulance and drove her off somewhere. She never learned how to read, so we never got any letters from her. The lonely and the sick were put in special places. They hid them. But no one knows where. Write this down . . .

The whole village felt sorry for her. We took care of her, like she was a little girl. Someone would chop wood for her, someone else would bring milk. Someone would sit in the house with her of an evening, heat the stove. Two years we all lived in other places, then we came back to our houses. Tell her that her house is still there. The roof is still there, the windows. Everything that’s broken or been stolen, we can fix. If you just tell us her address, where she’s living and suffering, we’ll go there and bring her back. So that she won’t die of sorrow. I beg you. An innocent spirit is suffering among strangers . . .

There’s one other thing about her, I forgot. When something hurts, she sings this song. There aren’t any words, it’s just her voice. She can’t talk. When something hurts, she just sings: a-a-a. It makes you feel sorry.

Mariya Volchok, neighbor

THREE MONOLOGUES ABOUT A HOMELAND

Speaking: The K. family—mother and daughter, plus a man who doesn’t speak a word (the daughter’s husband).

Daughter:

At first I cried day and night. I wanted to cry and talk. We’re from Tajikistan, from Dushanbe. There’s a war there.

I shouldn’t be talking about this now. I’m expecting—I’m pregnant. But I’ll tell you. They come onto the bus one day to check our passports. Just regular people, except with automatic weapons. They look through the documents and then push the men out of the bus. And then, right there, right outside the door, they shoot them. They don’t even take them aside. I would never have believed it. But I saw it. I saw how they took out two men, one was so young, handsome, and he was yelling something at them. In Tajik, in Russian. He was yelling that his wife just gave birth, he has three little kids at home. But they just laughed, they were young, too, very young. Just regular people, except with automatic weapons. He fell. He kissed their sneakers. Everyone was quiet, the whole bus. Then we drove off, and we heard: ta-ta-ta. I was afraid to look back. [Starts crying.]

I’m not supposed to be talking about this. I’m expecting a baby. But I’ll tell you. Just one thing, though: don’t write my last name. I’m Svetlana. We still