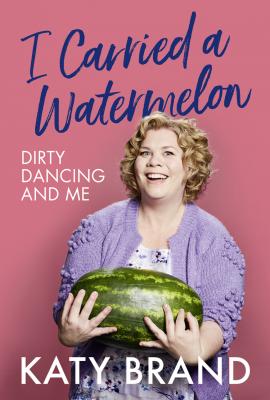

I Carried a Watermelon: Dirty Dancing and Me. Katy Brand

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу I Carried a Watermelon: Dirty Dancing and Me - Katy Brand страница 9

is even prepared to tell an absolute stonking lie because she fears she will never get near it again.

is even prepared to tell an absolute stonking lie because she fears she will never get near it again.

Ah yes, Vivian. Vivian Pressman, brilliantly and subtly played by Miranda Garrison (although on first viewing I was convinced it was British actress Lesley Joseph, of Birds of a Feather fame …), brings us to a different kind of sex represented in Dirty Dancing. In fact, there’s a lot of shagging in Dirty Dancing. It drives the plot as much as the dancing does. And a lot of general sexiness – everyone looks pretty up for it all the time. Even Baby’s parents, Jake and Marge Houseman, have a naughty twinkle in their eyes, to be frank.

The air of melancholy and loneliness, and faded glamour Vivian brings can be lost in the frenzy of the first few viewings, but it’s there and it’s important. When I first watched it, I was too overwhelmed by it all to really take her, and her storyline, in. But later in life I have grown quite fascinated by it.

It’s Max Kellerman’s introduction to Vivian early in the film that sets the tone. He watches her gracefully dancing with Johnny, a wry and sympathetic smile on his face as he explains to the Housemans that she is a ‘bungalow bunny’ – women who spend all week alone at Kellerman’s while their wealthy husbands work, arriving at the weekend only to ignore them further, choosing to play cards instead of dancing with their wives. It is clear that Vivian and Johnny have some form of quiet arrangement, and that she is one of the women ‘stuffing diamonds in his pockets’ that he refers to later in his speech to Baby about his experience of being sexually exploited in the resort. There are no sniggers, or jibes about older women. He doesn’t suggest that he is lowering himself, or is repulsed by her. There is an implied competition with Baby of course, which Baby wins, and yes, her youth is part of it, but also there is a sense that Vivian represents a jaded, toxic scene that we wish Johnny was not involved with, and Baby is his route out.

My only criticism of this storyline is that, as I have got older, I have wished to learn more about Vivian. There’s so clearly a real story there, and she would have things to say about life, men, and probably a whole lot else. Probably more than Marge Houseman, who doesn’t seem to have a lot going on, and even less to contribute, save for her final bark at her husband, ‘Sit down, Jake’, as Baby and Johnny take to the stage in front of everyone.

It took me a while to realise what was going on in one of the final scenes, where Vivian’s husband Mo offers Johnny some cash in hand for ‘extra dance lessons’ for his wife, because he will be busy playing cards all night. It took me even longer to understand that Johnny’s decision to reject the offer of cash (and therefore reject Vivian herself) from Mo Pressman, in front of her, motivates her to report him to his boss for stealing the purses and wallets that have been going missing around the resort. This then leads to Baby having to expose their affair by providing his alibi, while accusing the old couple, the Schumachers (who are found to be the real thieves). ‘I know he didn’t take them,’ she says falteringly, her eyes flicking briefly to her shocked father, ‘I know he was in his room all night. And the reason I know … is because I was with him.’ Wow – what a moment! Your heart could beat right out of your chest. She has just told everyone she is shagging the arse off her dancing instructor, right there, over breakfast.

There’s a lot to learn from this film when you are 11 years old. The mysterious and complicated world of adults was slowly coming into focus for me, but a lot still went over my head. There are layers I missed the first time I watched Dirty Dancing that would later reveal themselves with repeat viewings (even to this day, Vivian Pressman is now a pretty vivid character for me, rather than a slightly tragic side-show). I remember around this period (the early 1990s) hearing the phrase, ‘Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned’, for example, and gaining some insight into its meaning because of Vivian’s actions. To make herself feel better after Johnny’s rejection, she goes straight to nasty Robbie Gould, the waiter, and is discovered on top of him by Lisa, Baby’s sister, who arrives ready to let him pop her cherry. And all the while, a stone’s throw away in another cabin, Johnny and Baby are having another world-beating shag. It’s a busy night.

The moment where, in the harsh early morning light, a grim-faced Vivian, free of make-up, exits Robbie’s cabin, and, as she tucks her tights into her evening bag, looks up to see Baby and Johnny, the image of wholesome sexuality, kissing each other goodbye after a night of love and tenderness, has got to be one of the bleakest images in romantic cinema. In fact, it has saved me from some seriously ill-advised, on-the-rebound-style hook ups over the years – I just picture myself as Vivian at dawn, still in her party dress, no tights, wondering who’s using who, and it’s enough to make me order a cab home. Thank you, Viv.

So now, let’s deal with Neil. Poor Neil Kellerman represents all those men who inexplicably believe themselves to be catnip to women everywhere, when in fact they really couldn’t be less sexually appealing. Even I, aged 11, understood that this man is not the one you want, even though he is intent on telling you that he is all you could ever dream of. He is the absolute antithesis of Johnny, and a sexual wasteland. A date with him would leave you about as moist as a beech-nut husk stranded in the midday sun. Mere mention of the line, ‘I love to watch your hair blowing in the breeze’, to any woman familiar with the film and therefore the scene where Neil invites Baby to come for an evening walk, will result in an instant and uncontrollable physical reaction of pure cringing disgust. Try it – honestly, you’ll be amazed at the power those ten words can have. In fact, you don’t even have to have seen the film.

Crucially, Neil can’t dance. And this, to writer and retired dancer Eleanor Bergstein, essentially consigns any man to the sexual slag heap. For Bergstein, dancing is the greatest indicator of sexual prowess and compatibility. That’s why it’s called Dirty Dancing. Even more criminal than not being able to dance is not being able to dance while believing you can, a flaw Neil exhibits when he walks into the studio to talk to Johnny before the big end-of-season show. Baby tells him that she’s just there to have some ‘extra dance lessons’. We see Neil raise his hands, and gyrate a little, and utter the words, ‘I can teach you, kid,’ which will induce a vomit response in anyone who now firmly understands that dancing = sex. No, Neil, you can’t. No, no, no.

But who am I to judge? Even though I knew every inch of what they were up to, how sex was and wasn’t meant to be done, who to do it with – ideally – and when, what you should and shouldn’t need to wear to get it, there was nothing much happening with me in that department in real life. It was, shall we politely say with a cough, ‘theoretical’. That is, until I went to my first hip hop club in London, far from home, far from church, with a group of new and exciting friends I had met at a drama club.

I had always liked hip hop, rap, R’n’B – I can’t say that I was particularly knowledgeable about them, or that my tastes within the genre were sophisticated, but they were unusual for the time and place I grew up. I went to a comprehensive school in Hertfordshire. It was mixed socially, but predominantly white. Most people were into guitar music and pop. I found bands such as Radiohead and Nirvana made me semi-suicidal, and instead hoovered up the likes of Arrested Development, The Fugees and Blackstreet, which were the bands in those genres that made it to the Top 40 in the 1990s. So although my tastes were uncommon in my little part of the Home Counties, I was still well within the parameters of what was available to buy from the music section of Woolworth’s in town. There was nothing especially cool or underground about me – I just liked what I liked.

Dancing to Nirvana in a nightclub is very, very different to dancing to Blackstreet. Very. Different. The first time I went to a club playing this sort of music I was 17 years old, and – thanks to Dirty Dancing – I thought, ‘Yes, this is it – this is what I want. I know how to do this.’ And I dived in.

And it was here that I had my second ever snog, and let me say it was very, very different to the first one. Very. Different. It had started