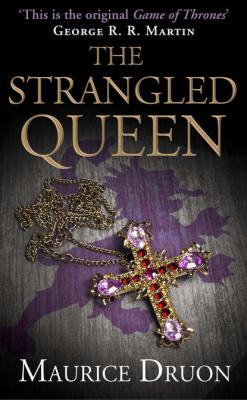

The Strangled Queen. Морис Дрюон

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу The Strangled Queen - Морис Дрюон страница 4

a fortress battered by the winds, drenched by the mists, built to accommodate two thousand soldiers and which now held no more than one hundred and fifty, above a valley of the Seine from which war had long ago retreated.

a fortress battered by the winds, drenched by the mists, built to accommodate two thousand soldiers and which now held no more than one hundred and fifty, above a valley of the Seine from which war had long ago retreated.

‘The Queen of France’s gaoler,’ the Captain of the Fortress repeated to himself; ‘it needed but that.’

No one was praying; everyone pretended to follow the service while thinking only of himself.

‘Requiem æternam dona eis domine,’ the Chaplain intoned.

He was thinking with fierce jealousy of priests in rich chasubles at that moment singing the same notes beneath the vaults of Notre-Dame. A Dominican in disgrace, who had, upon taking orders, dreamed of being one day Grand Inquisitor, he had ended as a prison chaplain. He wondered whether the change of reign might bring him some renewal of favour.

‘Et lux perpetua luceat eis,’ responded the Captain of the Fortress, envying the lot of Alain de Pareilles, Captain-General of the Royal Archers, who marched at the head of every procession.

‘Requiem æternam … So they won’t even issue us with an extra ration of wine?’ murmured Private Gros-Guillaume to Sergeant Lalaine.

But the two prisoners dared not utter a word; they would have sung too loudly in their joy.

Certainly, upon that day, in many of the churches of France, there were people who sincerely mourned the death of King Philip, without perhaps being able to explain precisely the reasons for their emotion; it was simply because he was the King under whose rule they had lived, and his passing marked the passing of the years. But no such thoughts were to be found within the prison walls.

When Mass was over, Marguerite of Burgundy was the first to approach the Captain of the Fortress.

‘Messire Bersumée,’ she said, looking him straight in the eye, ‘I wish to talk with you upon matters of importance which also concern yourself.’

The Captain of the Fortress was always embarrassed when Marguerite of Burgundy looked directly at him and on this occasion he felt even more uneasy than usual.

He lowered his eyes.

‘I shall come to speak with you, Madam,’ he replied, ‘as soon as I have done my rounds and changed the guard.’

Then he ordered Sergeant Lalaine to accompany the Princesses, recommending him in a low voice to behave with particular correctness.

The tower in which Marguerite and Blanche were confined had but three high, identical, circular rooms, placed one above the other, each with hearth and overmantel and, for ceiling, an eight-arched vault; these rooms were connected by a spiral staircase constructed in the thickness of the wall. The ground-floor room was permanently occupied by a detachment of their guard – a guard which caused Captain Bersumée such anxiety that he had it relieved every six hours in continuous fear that it might be suborned, seduced or outwitted. Marguerite lived in the first-floor room and Blanche on the second floor. At night the two Princesses were separated by a heavy door closed halfway up the staircase; by day they were allowed to communicate with each other.

When the sergeant had accompanied them back, they waited till every hinge and lock had creaked into place at the bottom of the stairs.

Then they looked at each other and with a mutual impulse fell into each other’s arms crying. ‘He’s dead, dead.’

They hugged each other, danced, laughed and cried all at once, repeating ceaselessly, ‘He’s dead!’

They tore off their hoods and freed their short hair, the growth of seven months.

Marguerite had little black curls all over her head, Blanche’s hair had grown unequally, in thick locks like handfuls of straw. Blanche ran her hand from her forehead back to her neck and, looking at her cousin, cried, ‘A looking-glass! The first thing I want is a looking-glass! Am I still beautiful, Marguerite?’

She behaved as if she were to be released within the hour and had now no concern but her appearance.

‘If you ask me that, it must be because I look so much older myself,’ said Marguerite.

‘Oh no!’ Blanche cried. ‘You’re as lovely as ever!’

She was sincere; in shared suffering change passes unnoticed. But Marguerite shook her head; she knew very well that it was not true.

And indeed the Princesses had suffered much since the spring: the tragedy of Maubuisson coming upon them in the midst of their happiness; their trial; the appalling death of their lovers, executed in their presence in the Great Square of Pontoise; the obscene shouts of the populace massed on their route; and after that half a year spent in a fortress; the wind howling among the eaves; the stifling heat of summer reflected from the stone; the icy cold suffered since autumn had begun; the black buckwheat gruel that formed their meals; their shirts, rough as though made of hair, and which they were allowed to change but once every two months; the window narrow as a loophole through which, however you placed your head, you could see no more than the helmet of an invisible archer pacing up and down the battlements – these things had so marked Marguerite’s character, and she knew it well, that they must also have left their mark upon her face.

Perhaps Blanche with her eighteen years and curiously volatile character, amounting almost to heedlessness, which permitted her to pass instantaneously from despair to an absurd optimism – Blanche, who could suddenly stop weeping because a bird was singing beyond the wall, and say wonderingly, ‘Marguerite! Do you hear the bird?’ – Blanche, who believed in signs, every kind of sign, and dreamed unceasingly as other women stitch, Blanche, perhaps, if she were freed from prison, might recover the complexion, the manner and the heart of other days; Marguerite, never. There was something broken in her that could never be mended.

Since the beginning of her imprisonment she had never shed so much as a single tear; but neither had she ever had a moment of remorse, of conscience or of regret.

The Chaplain, who confessed her every week, was shocked by her spiritual intransigence.

Not for an instant had Marguerite admitted her own responsibility for her misfortunes; not for an instant had she admitted that, when one is the granddaughter of Saint Louis, the daughter of the Duke of Burgundy, Queen of Navarre and destined to succeed to the most Christian throne of France, to take an equerry for lover, receive him in one’s husband’s house, and load him with gaudy presents, constituted a dangerous game which might cost one both honour and liberty. She felt that she was justified by the fact that she had been married to a prince whom she did not love, and whose nocturnal advances filled her with horror.

She did not reproach herself with having acted as she had; she merely hated those who had brought her disaster about; and it was upon others alone that she lavished her despairing anger: against her sister-in-law, the Queen of England, who had denounced her, against the royal family of France who had condemned her, against her own family of Burgundy who had failed to defend her, against the whole kingdom, against fate itself and against God. It was upon others that she wished so thirstily to be avenged when she thought that, on this very day, she should have been side by side with the new king, sharing in power and majesty, instead of being imprisoned, a derisory queen, behind walls twelve feet thick.

Blanche put her arm round her neck.

‘It’s all over now,’ she said. ‘I’m sure, my dear, that our misfortunes are over.’

‘They