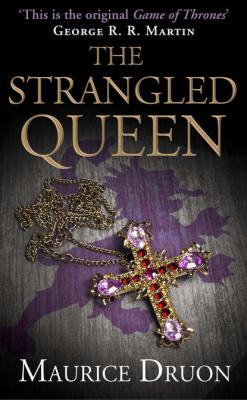

The Strangled Queen. Морис Дрюон

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу The Strangled Queen - Морис Дрюон страница 5

had a plan in mind, thought out during Mass, whose outcome she could not yet clearly envisage. Nevertheless she wished to turn the situation to her own advantage.

had a plan in mind, thought out during Mass, whose outcome she could not yet clearly envisage. Nevertheless she wished to turn the situation to her own advantage.

‘You will let me speak alone with that great lout of a Bersumée, whose head I should prefer to see upon a pike than upon his shoulders,’ she added.

A moment later the locks and hinges creaked at the base of the tower.

The two women put their hoods on again. Blanche went and stood in the embrasure of the narrow window; Marguerite, assuming a royal attitude, seated herself upon the bench which was the only seat in the room. The Captain of the Fortress came in.

‘I have come, Madam, as you asked me to,’ he said.

Marguerite took her time, looking him straight in the eye.

‘Messire Bersumée,’ she asked, ‘do you realize whom you will be guarding from now on?’

Bersumée turned his eyes away, as if he were searching for something in the room.

‘I know it well, Madam, I know it well,’ he replied, ‘and I have been thinking of it ever since this morning, when the courier woke me on his way to Criquebœuf and Rouen.’

‘During the seven months of my imprisonment here I have had insufficient linen, no furniture or sheets; I have eaten the same gruel as your archers and I have but one hour’s firing a day.’

‘I have obeyed Messire de Nogaret’s orders, Madam,’ replied Bersumée.

‘Messire de Nogaret is dead.’2

‘He sent me the King’s instructions.’

‘King Philip is dead.’

Seeing where Marguerite was leading, Bersumée replied, ‘But Monseigneur de Marigny is still alive, Madame, and he is in control of the judiciary and the prisons, as he controls all else in the kingdom, and I am responsible to him for everything.’

‘Did this morning’s courier give you no new orders concerning me?’

‘None, Madam.’

‘You will receive them shortly.’

‘I await them, Madam.’

For a moment they looked at each other in silence. Robert Bersumée, Captain of Château-Gaillard, was thirty-five years old, at that epoch a ripe age. He had that precise, dutiful look professional soldiers assume so easily and which, from being continually assumed, eventually becomes natural to them. For ordinary everyday duty in the fortress he wore a wolfskin cap and a rather loose old coat of mail, black with grease, which hung in folds about his belt. His eyebrows made a single bar above his nose.

At the beginning of her imprisonment Marguerite had tried to seduce him, ready to offer herself to him in order to make him her ally. He had failed to respond for fear of the consequences. But he was always embarrassed in Marguerite’s presence and felt a grudge against her for the part she had made him play. Today he was thinking, ‘Well, there it is! I could have been the Queen of France’s lover.’ And he wondered whether his scrupulously soldierly conduct would turn out well or ill for his prospects of promotion.

‘It has been no pleasure to me, Madam, to have had to inflict such treatment upon women, particularly of such high rank as yours,’ he said.

‘I can well believe it, Messire, I can well believe it,’ replied Marguerite, ‘because one can clearly see how knightly you are by nature and that you have felt great repugnance for your orders.’

As his father was a blacksmith and his mother the daughter of a sacristan, the Captain of the Fortress heard the word ‘knightly’ with considerable pleasure.

‘Only, Messire Bersumée,’ went on the prisoner, ‘I am tired of chewing wood to keep my teeth white and of anointing my hands with the grease from my soup to prevent my skin chapping with the cold.’

‘I can well understand it, Madam, I can well understand it.’

‘I should be grateful to you if from now on you would see to it that I am protected from cold, vermin and hunger.’

Bersumée lowered his head.

‘I have no orders, Madam,’ he replied.

‘I am only here because of the hatred of King Philip, and his death will change everything,’ went on Marguerite with such assurance that she very nearly convinced herself. ‘Do you intend to wait till you receive orders to open the prison doors before you show some consideration for the Queen of France? Don’t you think you would be acting somewhat stupidly against your own interests?’

Soldiers are often indecisive by nature, which predisposes them towards obedience and causes them to lose many a battle. Bersumée was as slow in initiative as he was prompt in obedience. He was loud-mouthed and ready with his fists towards his subordinates, but he had very little ability to make up his mind when faced with an unexpected situation.

Between the resentment of a woman who, so she said, would be all-powerful tomorrow, and the anger of Monseigneur de Marigny who was all-powerful today, which risk was he to take?

‘I also desire that Madame Blanche and myself,’ continued Marguerite, ‘may be allowed to go outside the fortifications for an hour or two a day, under your guardianship if you think proper, so that we may have a change of scene from battlements and your archers’ pikes.’

She was going too fast and too far. Bersumée saw the trap. His prisoners were trying to slip through his fingers. They were therefore not so certain after all of their return to Court.

‘Since you are Queen, Madam, you will understand that I owe loyalty to the service of the kingdom,’ he said, ‘and that I cannot infringe the orders I have received.’

Having said this, he went out so as to avoid further argument.

‘He’s a dog,’ cried Marguerite when he had left, ‘a guard-dog who is good for nothing but to bark and bite.’

She had made a false move and was beside herself to find some means of communicating with the outside world, receive news, and send letters which would be unread by Marigny. She did not know that a messenger, selected from among the first lords of the kingdom, was already on his way to lay a strange proposal before her.

2

Robert of Artois

‘YOU’VE GOT TO BE READY for anything when you’re a Queen’s gaoler,’ said Bersumée to himself as he left the tower. He was seriously perturbed, filled with misgiving. So important an event as the King’s death could not but result in a visitor to Château-Gaillard from Paris. So Bersumée, shouting at the top of his voice, made haste to make his garrison ready for inspection. On that count at least he intended to be blameless.

All day there was such commotion in the fortress as had not been seen since Richard Cœur-de-Lion. There was much sweeping and cleaning. Had an archer lost his