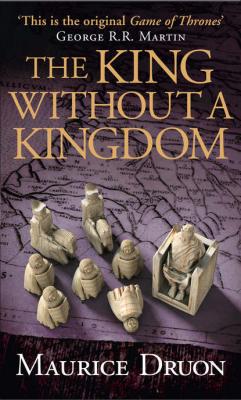

The King Without a Kingdom. Морис Дрюон

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу The King Without a Kingdom - Морис Дрюон страница 16

have the chance to rebuild it and make it even more beautiful than before …’

have the chance to rebuild it and make it even more beautiful than before …’

Good men of the cloth are joyous, my nephew, remember that. I am wary of overly severe fasters with their long faces and their burning, close-set eyes, as if they had spent too long squinting at hell. Those God honours most highly by calling them to His service have an obligation to show in their manner the joy this brings them; it is an example and a courtesy that they owe to other mortals.

In the same way as kings, since God has elevated them over and above all other men, they have the duty to show self-control. Messire Philip the Fair who was a paragon of true majesty, condemned without showing anger; and he mourned without shedding a tear.

On the occasion of Monsieur of Spain’s murder, that I was telling you about yesterday, King John showed all too well, and in the most pitiful fashion, that he was incapable of the slightest restraint in his passions. Pity is not what a king should inspire; it is better that one believes him impervious to pain. Four long days our king refrained from speaking a word, not even to say if he wanted to eat or drink. He kept to his rooms, acknowledging nobody, abandoning control of himself, eyes reddened and brimming, stopping suddenly to burst into tears. It was pointless talking to him about any business. Had the enemy invaded his palace, he would have let himself be taken by the hand. He hadn’t shown a quarter of such grief when the mother of his children, Madame of Luxembourg, passed away, something that the Dauphin Charles didn’t fail to mention. It was in fact the very first time that he was seen to show contempt for his father, going so far as to tell him that it was indecent to let himself go like this. But the king would hear nothing.

He would emerge from his state of despondency only to start screaming … that his charger be saddled immediately; screaming that his army should be mustered; screaming that he would speed to Évreux to take his revenge, and that everyone would be trembling with fear … Those close to him had great difficulty in bringing him to his senses and explaining to him that to get together his army, even without his arrièreban,20 would take at least one month; that if he really wanted to attack Évreux, he would inevitably force a rift with Normandy; he should recall, as a counter-argument for this, that the truce with the King of England was about to expire, and that monarch might be tempted to take advantage of the chaos, the kingdom could be jeopardized.

He was also shown that, perhaps if he had simply respected his daughter’s marriage contract and kept his promise to give Angoulême to Charles of Navarre, instead of offering it as a gift to his dear constable …

John II stretched out his arms wide and proclaimed: ‘Who am I then, if I can do nothing? I can clearly see that not one of you loves me, and that I have lost my support.’ But in the end, he stayed at home, swearing to God that never would he know joy until he had been avenged.

Meanwhile, Charles the Bad didn’t remain idle. He wrote to the pope, he wrote to the emperor, he wrote to all the Christian princes, explaining to them that he hadn’t wanted Charles of Spain’s death, but only to seize him for insults received, and the harm he had suffered at his hand; truly his men had overstepped his orders, but he was prepared to assume responsibility for it all and stand up for his relatives, friends and servants who had been driven, in the tumult of Laigle, by an overzealous concern for his well-being.

Having set up the ambush like a highway brigand, this is how he portrayed himself, wearing the gloves of a knight.

And most importantly he wrote to the Duke of Lancaster, who was to be found in Malines, and also to the King of England himself. We got wind of these letters when things began to turn sour. The Bad One certainly didn’t beat about the bush. ‘If you summon your captains in Brittany to ready themselves, as soon as I send for them, to enter in Normandy, I will grant them good and sure passage. You should know, dearest cousin, that all the nobles of Normandy are with me in death as in life.’ With the murder of Monsieur of Spain, our man had chosen rebellion; now he was moving towards treason. But at the same time, he cast upon King John the Ladies of Melun.

You don’t know whom we mean by that name? Ah! It’s raining. It was to be expected; this rain has been threatening us from the outset. Now you will bless my palanquin, Archambaud, rather than having water running down your neck, beneath your coathardy, and mud caking you to the waist …

The Ladies of Melun? They are the two queens dowager, and Joan of Valois, Charles’s child-bride, who is awaiting puberty. All three live in the Castle of Melun, that is called the Castle of the Three Queens, or even the Widows’ Court.

First of all there is Madame Joan of Évreux, King Charles IV’s widow and aunt to our Bad One. Yes, yes, she is still alive; she isn’t at all as old as one would think. She is barely a day over fifty; she is four or five years younger than me. She has been a widow for twenty-eight years already, twenty-eight years of wearing white. She shared the throne just three years. But she has remained an influence in the kingdom. She is the most senior, the very last queen of the great Capetian dynasty. Yes, of the three confinements she went through … three girls, of which only one, the one birthed after the king’s death, is still living … had she given birth to a boy, she would have been queen mother and regent. The dynasty came to an end in her womb. When she says: ‘Monseigneur of Évreux, my father … my uncle Philip the Fair … my brother-in-law Philip the Tall …’ a hush descends. She is the survivor of an undisputed monarchy, and of a time when France was infinitely more powerful and glorious than today. She is guarantor for the new breed. So, there are things that are not done because Madame of Évreux would disapprove of them.

In addition to this, it is said around her: ‘She is a saint.’ You have to admit that it doesn’t take much when one is queen, to be looked upon as a saint by a small and idle court where singing others’ praises passes as an occupation. Madame Joan of Évreux gets up before dawn; she lights her candle herself so as not to disturb her ladies-in-waiting. Then she begins to read her book of hours, the smallest in the world so we are led to believe, a gift from her husband who had commissioned it from a master limner,21 Jean Pucelle. She spends much time in prayer and regularly gives alms. She has spent twenty-eight years repeating that, as she had been unable to give birth to a son, she had no future. Widows live on obsessions. She could have carried more weight in the kingdom if she had been blessed with intelligence in proportion to her virtue.

Then there is Madame Blanche, Charles of Navarre’s sister, second wife of Philip VI, a queen for just six months, barely time enough to get accustomed to wearing a crown. She has the reputation of being the most beautiful woman of the kingdom. I saw her, not long ago, and can willingly confirm this judgement. She is now twenty-four, and for the last six years has been wondering what the whiteness of her skin, her enamel eyes and her perfect body are all for. Had nature endowed her with a less splendid appearance, she would be queen now, since she was intended for King John! The father only took her for himself because he was transfixed by her beauty.

Not long after she had accompanied her husband’s body to the grave that was prepared, she was proposed to by the King of Castile, Don Pedro, whose subjects had named the Cruel. She responded, rather hastily perhaps, that: ‘A Queen of France does not remarry.’ She was much praised for this display of grandeur. But she wonders to this day if it is not too great a sacrifice she has made for the sake of her title and whatever rights she still has to her former magnificence. The domain of Melun is her dower. She has made many improvements to it, but she can well change the carpets and tapestries that make up her bedroom at Christmas and Easter; she will always sleep there alone.

Finally, there is the other Joan, King John’s daughter, whose marriage had the effect of bringing on only storms. Charles of Navarre entrusted her to his aunt and his sister, until she was of an age to consummate the bond. That Joan is a little minx, as a girl of twelve can be, who remembers being a widow at six, and who knows herself to be queen without yet being