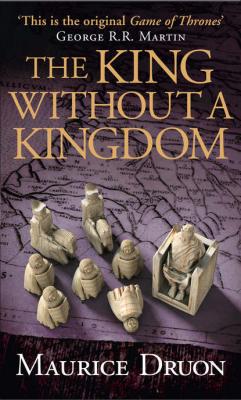

The King Without a Kingdom. Морис Дрюон

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу The King Without a Kingdom - Морис Дрюон страница 13

the one who calls himself Phoebus, and his other brother-in-law, the King of Aragon, Peter the Ceremonious, and also the King of Castile.

the one who calls himself Phoebus, and his other brother-in-law, the King of Aragon, Peter the Ceremonious, and also the King of Castile.

Now, one day, back in Pamplona, he was crossing a bridge on horseback when he met a delegation of Navarrese noblemen who had come to the city to bring him their grievances, as he had allowed their rights and privileges to be flouted. When Charles refused to hear them, things began to get a little heated; the new king then ordered his soldiers to seize those who were shouting closest to him, and, saying that one must be prompt in dealing out punishment if one wishes to command respect, further ordered that they be hanged immediately on the trees nearby.

I have noticed that when a prince resorts to capital punishment too quickly he is often giving in to fits of panic. In this Charles was no exception, as I believe his words are braver than his deeds. These brutal hangings would plunge Navarre into mourning, and soon by common consent he had earned the right to be called el Malo by his subjects, the Bad. He didn’t delay in moving away from his kingdom, whose government he left to his youngest brother Louis, only fifteen at the time, preferring to return to the bustle of the French court accompanied by his other brother Philip.

So, you may say, how can the Navarrese contingent have become so powerful and thick on the ground when in Navarre itself the king is widely hated, and even opposed by many of the nobility? Heh! My nephew, it is because this contingent is mostly made up of Norman knights from the county of Évreux. And what really makes Charles of Navarre dangerous for the French crown, more than his possessions in the south of the kingdom, are the lands he holds, or that he held, near Paris, such as the seigniories of Mantes, Pacy, Meulan, or Nonancourt, which command access to the capital from the westerly quarter of the country.

That danger King John understood well, or was made to understand; and for once in his life he showed proof of some common sense, endeavouring to make amends and reach an understanding with his Navarrese cousin. By which bond could he best tie his cousin’s hands? By a marriage. And what marriage could one offer him that would bind him to the throne as tightly as the union that had, six months long, made his sister Blanche Queen of France? Why, marriage with the eldest of the daughters of the king himself, little Joan of Valois. She was only eight years old, but it was a match worth the wait before it could be consummated. For that matter, Charles of Navarre had no shortage of lady friends to help him bide his time. Amongst others a certain demoiselle11 Gracieuse … yes, that is her name, or the one she answers to … The bride, little Joan of Valois, was herself already a widow, as she had been married once before, at the age of three, to a relative of her mother’s that God wasn’t long in taking back.

In Avignon, we looked favourably upon this betrothal, which seemed to us a strong enough bond to secure peace. This was because the contract resolved all the outstanding business between the two branches of the French royal family. First of all, the matter of the Count of Angoulême, betrothed for such a long time already to Charles’s mother, in exchange for his relinquishing the counties of Brie and Champagne, and exchanging them in turn for Pontoise and Beaumont, but it was an arrangement that was never executed. In the new agreement, the initial agreement was reverted to; Navarre would get Angoumois as well as several major strongholds and castellanies12 that would make up the dowry. King John made a forthright show of his own power in showering his future son-in-law with gifts. ‘You shall have this, it is my will; I shall give you that, it is my word …’

Navarre joked in intimate circles about his new relationship with King John. ‘We were cousins by birth; at one time we were going to be brothers-in-law, but as his father married my sister instead, I ended up being his uncle; and now I am to become his son-in-law.’ But while negotiating the contract, he proved most effective in expanding his prize. No particular contribution was asked of him, beyond an advance: one hundred thousand écus13 that were owed by King John to Parisian merchants, and were by the good grace of Charles to be paid back. However, he did not have the necessary liquid assets, either; the sum was procured for him from Flemish bankers, with whom he consented to leave some of his jewellery as guarantee. It was an easier thing to do for the king’s son-in-law than for the king himself …

It was during this transaction, I realize now, that Navarre must have made contact with the Prevost Marcel … about whom I should also write to the pope, to alert his holiness to the man’s scheming, which at present is something of a cause for concern. But that is another matter …

The sum of one hundred thousand écus was acknowledged in the marriage contract as being due to Navarre; it was to be paid to him in instalments, beginning straight away. Furthermore, he was made knight of the Order of the Star, and was even led to believe that he might become constable, though he was barely twenty years old. The marriage was celebrated in great style and jubilation.

And yet this exuberant friendship between the king and his son-in-law was soon to be soured and the two set at odds. Who caused this falling out? The other Charles, Monsieur of Spain, the handsome La Cerda, inevitably jealous of the favour surrounding Navarre, and worried to see the new star rising so high in the court’s firmament. Charles of Navarre has a failing that many young men share … and I strongly entreat you to guard against it, Archambaud … which consists in talking too much when fortune smiles on them; a demon seems to make them say wicked words that reveal far too much. La Cerda made sure he told King John of his son-in-law’s dubious character traits, spicing them up with his very own sauce. ‘He taunts you, my good sire; he thinks he can say exactly what he likes. You can no longer tolerate such offences to your majesty; and if you do put up with them, it is I who will not bear them, for your sake.’ He would drip poison into the king’s ear day after day. Navarre had said this, Navarre had done that; Navarre was drawing too close to the dauphin; Navarre was scheming with such and such an officer of the Great Council. No man is quicker than King John to fall for a bad idea about somebody else; nor more begrudging to abandon it. He is both gullible and stubborn, all at the same time. Nothing is easier than inventing enemies for him.

Soon he had the role of Lieutenant General of Languedoc, one of his gifts to Charles of Navarre, withdrawn. To whose benefit? To that of Charles of Spain. Then the high office of constable, left vacant since the beheading of Raoul of Brienne, was at long last to be filled: it was handed not to Charles of Navarre, but to Charles of Spain. Of the one hundred thousand écus that he should have been paid back, Navarre saw not a single one, while the king’s avowed friend was showered with presents and benefits. Lastly, lastly, the County of Angoulême, in spite of all the arrangements, was given to Monsieur of Spain, Navarre once more having to make do with a vague promise of a future trade-off.

Thus, where at first there was but coolness between Charles the Bad and Charles of Spain, there grew up abhorrence, and, soon after, open hatred. It was all too easy for Monsieur of Spain to point to Navarre’s behaviour and say to the king: ‘You see how true were my words, my good sire! Your son-in-law, whose evil plans I have unravelled, is taking a stand against your wishes. He takes it out on me, as he can see that I serve you only too well.’

Other times, when he was at the height of favour, he feigned a desire to go into exile from the court should the Navarrese brothers continue to speak ill of him. He spoke like a mistress: ‘I will leave for a deserted region, far from your kingdom, to live on the memory of the love that you have shown me. Or to die there! Because far from you, my soul will leave my body.’ They saw the king shed tears for his constable’s most strange devotion.

And as King John’s head was in a whirl with the Spaniard, and as he could only see the world through his eyes, he was most persistent in making an implacable enemy of the cousin that he had chosen as son-in-law in order to secure himself an ally.

I have already said this: a greater fool than this king is not to be found, nor one more injurious to himself … this would be of little harm if at the same time it had not been so damaging