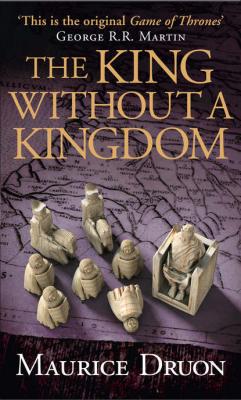

The King Without a Kingdom. Морис Дрюон

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу The King Without a Kingdom - Морис Дрюон страница 10

HEY! MY NEPHEW, I can see that you are taking to my palanquin and to the meals I am served here. And to my company, and to my company, of course. Do take some of this confit de canard that was given to us in Nontron. It is the town’s speciality. I don’t know how my chef managed to keep it warm for us …

Brunet! Brunet, you will tell my chef how much I appreciate his keeping the dishes warm; he prepares them for me beforehand, for the journey; he is most skilful. Ah! He has hot coals in his cart … No, no, I don’t mind being served the same food twice in a row, as long as I enjoyed it the first time. And I had found the confit quite delicious yesterday evening. Let us thank God that he provides for us so plentifully.

The wine is, admittedly, rather too young and thin. This is neither the Sainte-Foy nor the Bergerac, to which you are accustomed, Archambaud. Indeed, nor is it the wine of Saint-Émilion and Lussac, both of which are a delight, but which now all leave Libourne in heavily-loaded ships headed for England. French palates are not allowed them any more.

Isn’t it true, Brunet, that this has nothing on a tumbler of Bergerac? The knight Aymar Brunet is from Bergerac, and finds nothing in the world better than what is grown on home soil. I mock him a little about that.

This morning, the Papal Secretary Dom Francesco Calvo is keeping me company. I want him to refresh my memory on all the matters I will have to deal with in Limoges. We will be staying there two full days, maybe three. In any case, unless I am obliged to do so by some urgent business or express summons, I avoid travelling on Sundays. I want my escort to be able to attend church services and take some rest.

Ah! I can’t hide the fact that I am excited at the idea of seeing Limoges once more! It was my very first bishopric. I was … I was … I was younger than you are now, Archambaud; I was twenty-three years old. And I treat you like a youngster! It is a failing that comes with age, to treat youth as if it were still childhood, forgetting what one was oneself at the same age. You will have to correct me, my nephew, when you see me veering off along this path. Bishop! My first mitre! I was most proud of it, and I was soon to commit the sin of pride because of it. It was said of course that I owed my seat to favour, just as I had my first benefices, which were bestowed upon me by Clement V because he held my mother in high esteem; now it was said John XXII obtained the bishopric for me because our families had matched my last sister, your aunt Aremburge, to his grand-nephew, Jacques de la Vie. And to be totally honest, there was some truth to it. Being the pope’s nephew is a happy accident, but the benefit of it doesn’t last unless it be combined with nobility such as ours. Your uncle La Vie was a good man.

As for me, as young as I was, I do not believe I am remembered as a bad bishop in Limoges, or anywhere else. When I see so many hoary diocesans who know neither how to keep their flock nor their clergy in check, and who overwhelm us with their grievances and their legal proceedings, I tell myself that I did the job rather well, and without too much trouble. I had good vicars – here, pour me some more of that wine would you; I need to wash down the confit – and I left it up to those good vicars to govern. I ordered them never to disturb me except for the most serious matters, for which I was respected, and even a little feared. This arrangement afforded me the luxury of continuing my studies. I was already most knowledgeable in canon law; I called the finest professors to my residence to enable me to perfect my mastery of civil law. They came up from Toulouse, where I was awarded my degree, and which is as good a university as Paris, as densely populated with learned scholars. By way of recognition, I have decided … I wanted to let you know, my nephew, as I now have the opportunity; this is recorded in my last will and testament, in case I am not able to accomplish it during my lifetime. I have decided to found, in Toulouse, a college for poor Périgordian schoolchildren. Do take that hand towel, Archambaud, and dry your fingers.

It was also in Limoges that I began my studies in astrology. For this reason: the two sciences most necessary for the exercise of authority in government are indeed the science of law and the science of the stars. The former teaches us the laws that govern the relationships between men and the obligations they have towards each other, or with the kingdom, or with the Church, while the latter gives us knowledge of the laws that govern the relationships men have with Providence. The law and astrology; the laws of the earth, the laws of the heavens. I say that there is no denying it. God brings each of us into the world at the hour He so wishes, and this exact time is written on the celestial clock, which by His good grace, He has allowed us to read.

I know there are certain believers, wretched men, who deride astrology as a science because it abounds in charlatans and peddlers of lies. But that has always been the way; the old books tell us that paltry fortune-tellers and false wise men, hawking their predictions, were denounced by the ancient Romans and by the other ancient civilizations; that never stopped them seeking out the art of the good and the just observers of the celestial sphere, who often practised their skills in sacred places. Just so, it is not thought wise to close down all the churches because there exist simoniacal or intemperate priests.

I am so pleased to see that you share my opinions on this matter. It is the humble attitude proper for the Christian before the decrees of Our Lord, the Creator of all things, who stands behind the stars.

You would like to … but of course, my nephew, I will be delighted to do yours. Do you know your time of birth? Ah! That you will need to find out; send someone to your mother and ask her to give you the exact time of your first cry. Mothers remember such things.

As far as I am concerned, I have never received anything but praise for my practice of astral science. It enabled me to give useful advice to those princes who deigned to listen to me, and also to know the nature of any man I found myself up against and to be wary of those whose fate was adverse to mine. Thus I knew from the beginning that Capocci would be an opponent in all things, and I have always distrusted him. It is the stars that have guided me to the successful completion of a great many negotiations, and the making of as many favourable arrangements, such as the match for my sister in Durazzo, or the felicitous marriage of Louis of Sicily; and the grateful beneficiaries swelled my fortune accordingly. But first of all, it was to John XXII (may God preserve him; he was my benefactor) that this science was of the most invaluable service. Because Pope John himself was a great alchemist and astrologian; knowing of my devotion to the same art, and the distinction I had attained in it, impelled him to show increased favour for myself and inspired him to listen to the wishes of the King of France and make me cardinal at the age of thirty, which is a most unusual thing. And so I went to Avignon to receive my galero. You know how such a thing takes place. Don’t you?

The pope gives a grand banquet for the entrance of the new recruit to the Curia, to which he invites all the cardinals. At the end of the meal, the pope sits on his throne, poses the galero upon the head of the new cardinal, who remains kneeling and kisses first his foot, then his lips. I was too young for John XXII … he was eighty-seven at that time … to call me venerabilis frater; so he chose to address me with a dilectus filius. And before inviting me to stand up, he whispered in my ear: ‘Do you know how much your galero cost me? Six pounds, seven sols and ten deniers.’ It was in the way of that pontiff to humble you, precisely at that moment when you felt the most proud, always having a word of mockery for delusions of grandeur. Of all the days of my life there is not a single one of which I have kept a sharper memory. The Holy Father, all withered and wrinkled under his white zucchetto, which hugged his cheeks … It was the fourteenth of July of the year 1331 …

Brunet!