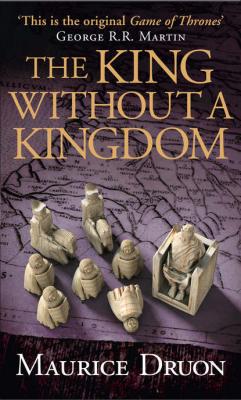

The King Without a Kingdom. Морис Дрюон

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу The King Without a Kingdom - Морис Дрюон страница 5

him the foolishness of his ways; he played the injured party, my Capocci; he withdrew; and while I race everywhere from Breteuil to Montbazon, from Montbazon to Poitiers, from Poitiers to Bordeaux, from Bordeaux to Périgueux, he merely writes everywhere, letters from Paris that undermine my negotiations. Ah! I sincerely hope I won’t come across him in Metz before the emperor.

him the foolishness of his ways; he played the injured party, my Capocci; he withdrew; and while I race everywhere from Breteuil to Montbazon, from Montbazon to Poitiers, from Poitiers to Bordeaux, from Bordeaux to Périgueux, he merely writes everywhere, letters from Paris that undermine my negotiations. Ah! I sincerely hope I won’t come across him in Metz before the emperor.

Périgueux, my Périgord. My God, was I seeing them for the last time?

My mother always assumed I would be pope. She made it clear to me on more than one occasion. It was why she made me wear the tonsure from the age of six, and arranged with Clement V, who was most fond of her, that I be enrolled as a papal scholar, and thus become apt to receive benefices. How old was I when she took me to him? ‘Lady Brunissande, may your son, whom we most specially bless, display in the place you have chosen for him those very virtues that we should expect from such noble lineage as his, and quickly rise to the highest offices of our Holy Church.’ No, no more than seven years old. He made me Canon of Saint-Front; my first cappa magna. Almost fifty years ago now … My mother saw me as pope. Was it a dream of maternal ambition, or a prophetic vision as women sometimes have? Alas! I do believe that I shall never be pope.

And yet, and yet, in my birth chart Jupiter is closely tied to the Sun, a beautiful culmination, the sign of domination and of a peaceful reign. No other cardinal has such favourable aspects as I. My configuration was a great deal better than Innocent’s on the day of his election. But there you have it, a peacetime reign, a reign in peace; and yet we are at war, amidst turmoil and storm. My stars are too perfect for the times we are living in. Those of Innocent – which speak of difficulties, errors, setbacks – are better suited to this sombre period. God matches men and moments in the world, and calls up popes who correspond to His grand design, such a man for greatness and glory, another for shadows and downfall.

If I hadn’t entered the Church, as my mother wished, I would be Count of Périgord, since my elder brother died without issue, the very same year as my first conclave, and the crown I couldn’t take on was assumed by my younger brother, Roger-Bernard. Neither pope nor count. Oh well, one has to accept the place where Providence puts us, and try to do the best one can there. I will most probably be one of those men, those leading figures who play a great role in their century, but are forgotten as soon as they die. People have short memories; they remember only the names of kings (Thy will be done, Lord, Thy will be done).

Then again, there is no point in mulling over the same things I have already been through a hundred times. It was seeing the Périgueux of my childhood, and my beloved collegiate Saint-Front, and having to leave them once more, that shook my soul. Let us look rather at this landscape that I am seeing perhaps for the last time. (Thank you, Lord, for granting me this joy.)

But why am I being carried at such breakneck speed? We have already passed Château-l’Évêque; from here to Bourdeilles will take no more than two hours. The day one sets off, one should always break the journey as soon as one can. The goodbyes are trying, the last-minute petitions, the clamour for final benedictions, the forgotten piece of luggage: one never leaves at the allotted time. But this stage of the journey is indeed brief.

Brunet! Hey! Brunet, my friend; go ahead and order that they ease the pace. Who is leading us in such haste? Is it Cunhac or La Rue? It is really unnecessary to shake my bones so. And then go and tell Monseigneur Archambaud, my nephew, to dismount. I invite him to share my palanquin. Thank you, go.

For the journey from Avignon I had my nephew Robert de Durazzo with me; he was a most agreeable travelling companion. He had the features of my sister Agnes, as well as those of our mother. Why on earth did he want to get himself slain by a gang of English louts at Poitiers, waging the wars of the King of France! Oh! I don’t disapprove of his fighting, even if I had to pretend to. Who would have thought that King John would be trounced in such fashion! He lined up thirty thousand men against six thousand, and that very evening was taken prisoner. Ah! The ridiculous prince, the simpleton! When he could have seized victory without ever engaging battle! If only he had accepted the treaty that I bore him as if on a platter of offerings!

Archambaud seems neither as quick-witted nor as brilliant as Robert. He hasn’t seen Italy, which frees up youth no end. Most likely it is he who will finally become Count of Périgord, God willing. It will broaden this young man’s mind to travel in my company. He has everything to learn from me. Once my orisons are said, I dislike being alone.

The Cardinal of Périgord speaks

IT IS NOT THAT I am loath to ride on horseback, Archambaud, nor that old age has made me incapable of doing so. Believe me, I am fully able to cover fifteen leagues on my mount, and I know a fair few younger than I that I would leave far behind. Moreover, as you can see, I always have a palfrey following me, harnessed and saddled in case I should feel the desire or need to mount it. But I have come to realize that a full day cantering in the saddle whets the appetite but not the mind, and leads to heavy eating and drinking rather than clear thinking, of the sort I often need to engage in when I have to inspect, rule or negotiate from the moment I arrive.

Many kings, first and foremost the King of France, would run their states more profitably if they wore their backs out less and exercised their brains for a change, and if they didn’t insist on conducting their most important affairs over dinner, at the end of a long journey or after the hunt. Take note that one doesn’t travel any slower in a palanquin, as I do, if one has good wadding in the stretcher, and the forethought to change it often. Would you care for a sugared almond, Archambaud? In the little coffer by your side. Well, pass me one would you?

Do you know how many days it took me to travel from Avignon to Breteuil in Normandy, in order to join King John, who was laying a nonsensical siege there? Go on, have a guess? No, my nephew; less than that. We left on the twenty-first of June, the very day of the summer solstice, and none too early at that. Because you know, or rather you don’t know what happens upon the departure of a nuncio, or two nuncios, as there were two of us on that occasion. It is customary for the entire College of Cardinals, following Mass, to escort the departing officials for a full league beyond the edge of town; and there is always a crowd following them, with people watching from both sides of the route. And we must advance at procession pace in order to give dignity to the cortège. Then we make a stop, and the cardinals line up in order of precedence and the Nuncio exchanges the kiss of peace with each one in turn. This whole ceremony takes up most of the morning. So we left on the twenty-first of June. And yet we were arrived in Breteuil by the ninth of July. Eighteen days. Niccola Capocci, my co-legate, was unwell. I must say, I had shaken him up no end, the spineless weakling. Never before had he travelled at such a pace. But one week later, the Holy Father had in his hands, delivered by messengers on horseback, the account of my first discussions with the king.

This time, we have no such need to rush. First, even if we are enjoying a mild spell, days are short at this time of year. I don’t recall November in Périgord being so warm, as warm as it is today. What beautiful light we have! But we are in danger of running into a storm as we advance to the north of the kingdom. I plan on taking roughly one month, so that we’ll be in Metz by Christmas, God willing. No, I am not in nearly as much of a hurry as last summer; despite all my efforts, that war took place, and King John was taken prisoner.

How could such ill fortune befall us? Oh! You are not the only one to be flabbergasted, my nephew. All Europe felt not inconsiderable surprise and has since been arguing about the root causes and the reasons. The misfortunes of kings