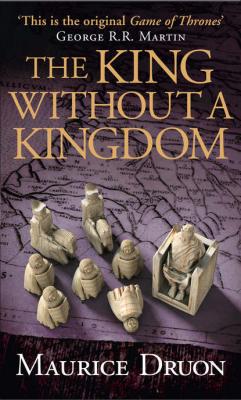

The King Without a Kingdom. Морис Дрюон

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу The King Without a Kingdom - Морис Дрюон страница 9

sixteen years old. She was beautiful, and blessed with a sharp wit. Plans were coming along well, the pope’s permission had been secured and the wedding was practically announced, even though during the terrible period we were living through, we were all wondering who would still be alive the next week.

sixteen years old. She was beautiful, and blessed with a sharp wit. Plans were coming along well, the pope’s permission had been secured and the wedding was practically announced, even though during the terrible period we were living through, we were all wondering who would still be alive the next week.

Because death continued to knock on every door. At the beginning of December the plague took the Queen of France herself, Madame Joan of Burgundy, the lame one, the bad queen. For her, decorum was scarcely enough to contain the cries of joy, and the people set to dancing in the streets. She was despised; your father must have told you so. She would steal her husband’s seal to have people thrown into prison; she would prepare poisoned baths for those guests she took a dislike to. She very nearly killed a bishop that way … The king occasionally beat her black and blue with torches; but he failed to mend her behaviour. I was most wary of the bad queen. Her suspicious nature filled the court with imaginary enemies. She was quick-tempered, a liar, a horrible person; she was a murderess. Her death seemed to be a delayed manifestation of heavenly justice. What’s more, immediately after her demise the scourge began to subside, as if this carnage, come from so far away, had had no other goal but to reach, at last, this harpy.

Of all the men in France, it was the king himself who was the most relieved by the news of her death. One month less one day later, in the cold of January, he remarried. Even as the widower of a universally hated woman, such haste was setting little store by social convention. But the worst was not in the timing. To whom was he wed? To his own son’s fiancée, Blanche of Navarre, the slip of a girl with whom he had fallen madly in love upon her first appearance at court. Although the French are happy to turn a blind eye to bawdiness, they hate to see their sovereign let himself be ruled by it in such fashion.

Philip VI was forty years older than the beauty he had snatched so brutally from the hand of his heir. And he couldn’t invoke a tradition of poorly matched princely couples, or the greater good of empires. He was setting a stone of scandal in his own crown, while inflicting upon his successor wounds of ridicule that would assuredly leave terrible scars. Philip and Blanche married in haste near Saint-Germain-en-Laye. John of Normandy of course did not attend. He had never been particularly fond of his father, and his father had offered him little affection in return. Now the son vowed the king nothing but hate.

And one month later, the heir also remarried. He was keen to put the insult he had suffered behind him. He made out to be delighted to settle for Madame of Boulogne, widow of the Duke of Burgundy. It was my venerable brother, the Cardinal Guy of Boulogne, who arranged the marriage in the interests of his family, while not forgetting to further his own interests as well. From a financial perspective, Madame of Boulogne was an excellent match. This should have cleared up the business affairs of the prince, who was a spendthrift second to none, but in fact he was only encouraged to squander yet more.

The new Duchess of Normandy was older than her mother-in-law; the two women produced a strange effect at court receptions, all the more so as any comparison between them – in terms of beauty and bearing – was hardly to the daughter-in-law’s advantage. Duke John was greatly vexed by this; he had let himself believe that he loved Madame Blanche of Navarre with all his heart, and he suffered torment seeing her, who had been so wickedly taken from him, next to his father, and being cosseted by him, in public, in the most idiotic fashion. This didn’t help nocturnal matters between Duke John and Madame of Boulogne; rather, the Duke was pushed further into the arms of Monsieur of Spain. Extravagance became his revenge. One would have thought that he was buying back his honour, not vaingloriously wasting money.

Besides, after the months of terror and grief we had endured, everybody was spending like mad. Especially in Paris. In and around the court was folly after the plague. They maintained that creating an abundance of luxury would provide work for the people. And yet we were hard put to see the effects in the hovels and the garrets. Between the princes with their rising debts and the poverty-stricken common people, there were the fixers and dealers who siphoned off the profit, big merchants like the Marcels, who deal in drapery, silks and other finery, and made themselves handsomely rich. Fashion became extravagant; Duke John, although he was already thirty-one years old, could be seen, together with Monsieur of Spain, wearing laced tunics so short his buttocks showed. People laughed at them no sooner had they passed by.

Madame Blanche of Navarre had been made queen sooner than originally planned; her reign was shorter than expected. Philip of Valois had come through both the war and the plague unscathed; he wasn’t to withstand love. All the years he was tied to a cantankerous, lame wife, he remained a handsome man, a little overweight but always robust, active, handling weaponry, riding fast, hunting long and hard. Six months of gallant prowess with his new, beautiful wife would undo him. It was obsession; it was frenzy. He would leave his bed with the thought uppermost in his mind of getting back in as soon as he could. He would ask his physicians for potions that would make him indefatigable in the act. What is it? Are you surprised? But of course, my nephew; despite being of the Church, or rather because we are of the Church, we need to be informed of such things, above all when they touch on the person of a king.

Madame Blanche was subjected to this obsession, the king’s passion was proved to her constantly; she was consenting, worried and flattered all at the same time. The king took to proclaiming publicly and with great pride that she wearied sooner than he. He lost weight. He lost interest in governing. Each week aged him a year. He died on the twenty-second of August 1350, at the age of fifty-seven, after a twenty-two-year reign.

Beneath his splendid exterior, this sovereign, to whom I was faithful … he was King of France, wasn’t he? And moreover I couldn’t forget that he was the one who had asked for the galero8 on my behalf … this monarch had been a pitiful leader and a disastrous financier. He had lost Calais, he had lost Aquitaine; he left Brittany in a state of revolt and a good many of the kingdom’s strongholds in doubt or in ruin. Above all he had lost prestige. I’m afraid so! Although he had bought Dauphiny.9 Nobody can be a perpetual catastrophe. It was I, it is good that you should know, who secured the deal, two years before Crécy. The Dauphin Humbert was so far in debt that he didn’t know whom to borrow from to pay back whomever. I will tell you the story in detail another day, if you are interested, how I went about getting the eldest son of France to wear the dauphin’s crown and bring Viennois back into the kingdom’s fold. In this way I can safely say, without wishing to boast, that I served France better than King Philip VI, as he only knew how to make it smaller, while I successfully expanded its borders.

Six years already! It has been six years since King Philip died and Monseigneur Duke John became King John II! Yet it still feels as if we are at the beginning of his reign, these six years have gone so quickly. Is it because our new king has achieved little one could deem noteworthy, or rather that the more one ages, the faster time seems to fly? At twenty, each month, each week, enriched with the new, seems to last for ever. You will see, Archambaud, when you get to be my age, if you do, that is, as I wish you may with all my heart, one turns around and one says to oneself: ‘How is it possible? Already another year gone by? How could it go so quickly!’ Perhaps it is because one takes up too many moments remembering, reliving times past.

And there it is; night has fallen. I knew we would be arriving at Nontron in the black of night.

Brunet! Brunet! Tomorrow we must leave before dawn, we have a long day’s travelling ahead of us, without the luxury of making any stops. So, everyone must be stocked up with provisions and we must be harnessed up in time. Who has gone ahead to Limoges to announce my arrival? Armand de Guillermis; that’s good. I send my knights on each one in turn to take care of my lodgings and the preparations for my welcome, one or two days in advance, no more. Just enough for the people to gather around eagerly, but not enough for the plaintiffs of the diocese to rush up and overwhelm me with their petitions for the king. The cardinal? Ah! We only found out the day before; alas, he is already gone. Otherwise, my nephew, I would be a veritable travelling tribunal.