Urban Protest. Arve Hansen

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Urban Protest - Arve Hansen страница 5

Hansen, Oslo, January 2021

Hansen, Oslo, January 2021

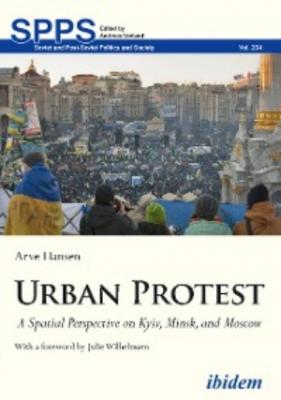

Figure 1: Post-electoral protest, Minsk, August 2020

Photo: Artem Podrez / Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/protesters-in-belarus-5119461/

1 Starting Point

Went to Kyiv […] metro still closed […] Got around the police blockades easily. […] I returned to the Maidan. Still felt like a safe place.

Kyiv, 20th February 2014

This excerpt is from one of the numerous field notes I made during the final days of the Ukrainian revolution (2013–2014). I was studying the events in Kyiv for a research project in East Slavic area studies (Hansen 2015), and went to the iconic site of the protests, Maidan (Independence Square), to observe the scene after the latest clashes between police and protesters. The contention in Kyiv had started three months earlier in response to the government’s sudden U-turn away from EU integration, and it had rapidly changed into a broad movement against the incumbent president Ianukovych. The conflict escalated into violence and, by this point, many people had been killed.

I arrived at Maidan for the second time that day at approximately four or five o’clock in the afternoon. At the time, rumour had it that 780 protesters had been killed over the previous 24 hours.1 The city was in a state of shock, and there was much uncertainty as to what would happen next. Yet, for some reason, I felt quite safe where I was standing.

I knew Maidan well: the entrances and exits, the many tunnels underneath, the seemingly random monuments mixed with intrusive advertising boards, kiosks, and architecture from all periods of Ukraine’s Soviet and post-Soviet past. Many times over the previous three months, I had wondered why this particular space had become the symbol of protest in Ukraine. Now, during these final days of the revolution, it was evident that the authorities had been unable to clear the square and stop protesters (or curious people like me) from entering it, despite numerous road blocks and a heavy riot police presence. Strangely, I also noticed that, even though everything was uncertain and no one knew whether the authorities would launch another attack, it didn’t feel particularly frightening to be where I was standing. If anything, I figured, I could always find a way out.

It became apparent to me then that Maidan was a very suitable place for protest, although I could not define precisely why.

Maidan is merely one of several examples of a town square that has turned into a location of great political significance. Actions and events spring immediately to mind at the mere mention of the Bastille, Red Square, Taksim, or Tahrir. We associate these places with the making of history: places where revolutions have been started, dictators ousted, or rebellions crushed.

Central urban spaces can thus create powerful imagery, and we intuitively understand that space has importance. Yet how are massive collective actions, such as the latest Ukrainian revolution, affected by urban public space? Or, to put it another way, how does urban space facilitate and/or inhibit public protests? These questions led me to the current study.

Figure 2: Maidan, Kyiv, February 2014a

Photo: Arve Hansen

Structure

This book describes the development of a spatial perspective on mass protests, a model which has been applied to three case studies: Kyiv, Minsk, and Moscow. It consists of ten chapters, divided into three main parts, one theoretical, one practical, and one concluding.

Part I opens in chapter 2 with a contextualisation of space and its central position in human society since the prehistoric era. It outlines a history of contention in urban public spaces, and explains why public spaces in the East Slavic region form the topic of this book.

Having established that urban public space has both a historic and a contemporary relevance, chapter 3 provides a systematic review, in two sections, of the existing research on protests and space. The first section (3.1) includes general theories within sociology and political science, and research on the specific conditions necessary for a collective action or revolution to occur. The second (3.2) looks at the various research on public (philosophy), physical (architecture, urban planning, geography), and contested space (urbanism). In the third section (3.3), an existing gap in the available research is identified. Even if connections between space and protest are discovered in the research literature, and from a variety of perspectives, none of the publications surveyed provide a systematic and generalised approach to the analysis of this causal relationship.

Chapter 4 continues the discussion of chapter 3 by providing two key definitions of mass protests (4.1) and urban public space (4.2), before stating the primary and secondary research questions of this book in full (4.3).

The theorising and development of the spatial perspective, from the conception of an idea to a complete theoretical model, are described in chapter 5. This includes the theory and approaches to theorising applied during the various stages of the model’s development (5.1), and some of the ethical considerations taken into account during the process (5.2), as well as my main reservation about developing a theory with a focus on geography. From this starting point, the development of the model is traced from its beginnings (5.4) through different stages of theorising and testing (5.5) to a description of the causal chains between urban space and mass protests employed in the final model (5.6). The project’s three case studies were written in parallel with the model’s development, and thus also reflect the various stages of the process. The first case is described as a prestudy (5.5.1), the second as a transitional study (5.5.3), and the third as the main study, demonstrating how the spatial perspective can be applied in its current form (5.7).

The causal mechanisms described in chapter five are explicated in chapter 6, including the model’s independent (6.1), intermediary (6.2),