Urban Protest. Arve Hansen

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Urban Protest - Arve Hansen страница 6

target="_blank" rel="nofollow" href="#ulink_b0c1efa3-015c-5ee2-b37d-65cebab14210">6.3).

target="_blank" rel="nofollow" href="#ulink_b0c1efa3-015c-5ee2-b37d-65cebab14210">6.3).

Part II consists of three chapters, each based to a large extent on the cases described in chapter 5: The prestudy of Maidan in Kyiv (chapter 7); the transitional study of October Square and Independence Square in Minsk (chapter 8); and the main study of Swamp Square in Moscow (chapter 9).

The single chapter of Part III—chapter 10—provides a final demonstration of the spatial perspective as applied to Republic Square (Place de la République), Paris, during a demonstration there on 6 January 2019 by the Yellow Vests (Fr.: Mouvement des gilets jaunes). The case study is used to demonstrate how the research questions outlined in chapter 4 have been answered, and forms the basis for arguing that the model can be used as a tool and a language to discuss spaces of contention and to provide new insights into the study of social movements and mass protests. Following a brief review of the contents, findings, and utility of this book, I then suggest a few ways in which the spatial perspective can be developed further.

1 The Ukrainian Ministry of Health later announced that the actual number of those killed was 82 (Ukrainian Ministry of Health 2014).

Part I

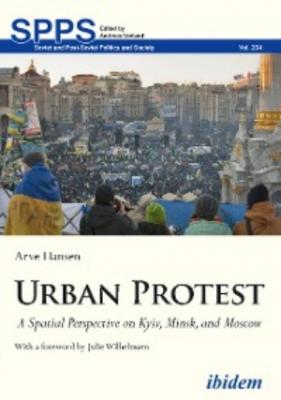

Figure 3: Maidan, Kyiv, December 2013

Photo: Arve Hansen

2 Space in Context

Human beings are cognitive creatures. We experience the world around us through our external sensory input, such as touch, smell, and sight, which our brains interpret based on our experiences, memory, and thoughts. One fundamental aspect of the experienced world is space and, consciously or subconsciously, we never stop interpreting the physical environment around us. This does not imply that we are necessarily aware of how this analysis is done, or even that it is being done in the first place. We often are unable to appreciate the full extent and impact of it or to explain how it works to a third party. Nevertheless, we are instinctively aware of our surroundings, sense their uses, opportunities, dangers, and risks, and adapt our behaviour accordingly.1

This keen sense of place has probably played a vital part in the survival of our species. When our early hominid ancestors, millions of years ago, entered new ground, instincts would be activated to provide information about the possibilities and dangers that particular space might provide. Exploring a new location, an individual would be sensitive to whether the space made them feel relaxed and safe, or alert and uneasy.

Over time, as the human capacity for social interaction evolved, space would come to be perceived not just as a place that might provide food and a chance to eat (or, conversely, a threat of being attacked and eaten), but also as a location for the increasingly complex social interactions between individuals within a group. Thus, the instinctive human perception of space would come to include information about other people and about the social interactions and relations occurring in that space. A newly arrived individual would, for example, soon sense whether this was a place to eat, relax, converse, and mate, or to be on its guard against other individuals in the group. It would know—with little conscious effort—where its allies and friends were, find the possible exits, sense whether it belonged in the group, and locate itself strategically according to its position in the social hierarchy: whether funny, loud, and boastful at the centre of the group, or reserved, quiet, and humble near one of the exits. Individuals who were oblivious to such social space would probably end up as outcasts, or worse, killed.

According to the Australian anthropologist Terrence Twomey (2014), our discovery and domestication of fire hundreds of thousands, perhaps even over a million years ago (Gowlett 2016) probably facilitated the evolution of human cooperation. Twomey explains how making a fire and keeping it going was a costly endeavour, yet the result was a good from which all the individuals in a group could greatly benefit. Hence, the domestication of fire would stimulate cooperation (Twomey 2014). We could therefore imagine that, for groups of hunter-gatherers in prehistoric times, the campfire would become one of the first dedicated spaces for social interaction. Here, people would flock together not only to eat and sleep in the relative safety from predators, insects, and cold weather, but also to process past events, discuss gains and risks, and make a plan of action for the day to come.

After the Neolithic Revolution of approximately 10 000 BCE, humans gradually started to live in fixed settlements and the new agricultural technology laid the foundation for explosive population growth (Bellwood and Oxenham 2008). In the new and increasingly urban setting, the locations of social interaction and planning would probably move from the campfire into urban spaces, such as marketplaces, town squares, or other focal points of growing villages and cities. We can find archaeological evidence from the Bronze and Iron ages, for instance, which indicate that social and deliberative spaces were valued to such an extent that they were rganizati as various forms of political institutions. Popular assemblies in urban space could be found in the Ancient Greek Agora (Anc. Greek.: ἀγορά), the Roman Forum Romanum, and the Slavic Veche (Rus.: вече); or, conversely, in the outskirts of settlements, such as the Scandinavian Thing (Icel.: þing).

However, urban spaces have some significant limitations as formal places of deliberation and public administration. Notably, the central plaza of a large city may not have enough physical space available for all people to attend, and large groups of people are often at risk of being affected by demagoguery. For these and other reasons, in most societies, public rganization moved into the remit of formal political institutions. Yet the cities’ urban spaces have remained as necessary parts of the landscape, needed in order for people to move from one place to another. Additionally, they function as places for trade, recreation, and social interaction. Urban spaces are often the location of joyful activities such as festivals and public entertainments, but also, sometimes, of floggings and executions. Some rulers might use the city’s focal point to display their might, too—for instance, in the form of army drills and parades. Moreover, although the majority of formal decisions now occur in buildings, the potential use value of urban space for people to discuss, deliberate, and decide on a course of action has not gone away.

Throughout human history, people have tended to congregate in central places in times of trouble. Such gatherings sometimes occur on the initiative of rulers to collectively find a solution to a shared problem (such as how to respond to an imminent invasion or the death of a prince). Yet, every so often, the ruling elites are themselves perceived as the problem, and the urban squares and marketplaces might be seized by the people and turned into arenas of opposition.

Figure 4: Althing, Iceland

Iceland’s form of popular assembly (Icel.: Alþingi) was first located on Thingvellir (the Assembly Fields, Icel.: Þingvellir)/Lögberg in the tenth century CE. Photo: Andrei Rogatchevski

2.1 Complexities of Urban Contention

Urban contention has a large number of aspects, and several of these are discussed in the next chapter. But there are three ways to look at and categorise urban collective actions