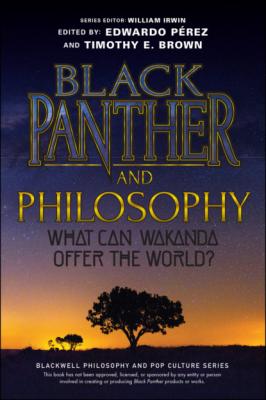

Black Panther and Philosophy. Группа авторов

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Black Panther and Philosophy - Группа авторов страница 16

nature of justice? To whom is justice owed? What does justice require? Notice the ambiguity in this last question – are we concerned with what justice requires ideally, or what justice requires given that…?

nature of justice? To whom is justice owed? What does justice require? Notice the ambiguity in this last question – are we concerned with what justice requires ideally, or what justice requires given that…?

“Every Breath You Take Is Mercy from Me.”

“Ideal” needn’t assume perfection, because ideal theories of justice can recognize and account for human fallibility, selfishness, scarcity, and the like. Nevertheless, ideal theory in philosophy works by abstracting away from messy complicating contingencies to provide a generalized model of the phenomenon in question. “What distinguishes ideal theory,” the philosopher Charles Mills explains, “is the reliance on idealization to the exclusion, or at least marginalization, of the actual.”1

John Rawls’s (1921–2002) massively influential book A Theory of Justice is one such example, a careful, systematic account of what justice requires ideally speaking. Here Rawls attempts to identify “the principles that characterize a well-ordered society under favorable circumstances.”2 It’s not that non-ideal questions are unimportant, but Rawls thinks we must construct an ideal vision of what justice requires first. By stepping outside of real-world conditions, contemplating the fundamental principles of justice we’d all choose if we were ignorant of our personal (and so possibly biasing) circumstances, we might come to recognize what Rawls calls justice as fairness.3

The characters in Black Panther are not contemplating justice from behind a veil of ignorance, nor applying ideal principles of justice to govern a nascent Wakandan society. Rather, Nakia is working to prevent human trafficking and to disrupt its existing networks. T’Challa is not just ensuring Wakanda’s safety and its vibranium supply, he is working to make Klaue pay for past crimes. Killmonger is not just asserting his right of Wakandan citizenship, but avenging his father’s murder and his own abandonment. They all seek some form of Aristotle’s corrective justice,4 to restore the conditions of justice damaged or destroyed by wrongdoing. They are concerned not with justice in the abstract, but with justice in their world, a world steeped in history.

“Almost by definition,” Mills argues, “it follows from the focus of ideal theory that little or nothing will be said on actual historic oppression and its legacy in the present, or current ongoing oppression, though these may be gestured at in a vague or promissory way (as something to be dealt with later).”5 Ideal theory can be powerful, but it is necessarily incomplete. Ideally, we would never do one another wrong, so it’s not surprising if an ideal theory of justice offers scant advice on what should happen after we do. A complete theory must address the aftermath of injustice as itself a special context of action and evaluation. Among other things, it must treat the experience and perpetration of injustice as something to be reckoned with, not just avoided in the future. It also must recognize the pitfalls and other difficulties we face on the path from injustice back to justice – the challenges of getting there from here.

Justice at the Museum and Beyond

Different approaches to achieving justice given that injustice has already happened vie for our consideration. Let’s look at three approaches that are especially relevant to the historical injustices in Black Panther: restitution, retribution, and reparation. The first of these focuses on victims’ losses and making them whole again; the second focuses on perpetrators’ offenses and punishments they deserve; the third focuses on repairing the relationships between victims and offenders and their communities, relationships that injustice has damaged or destroyed.

Let’s consider how each of these forms of corrective justice applies to the historical injustices of Black Panther, starting with the scene when we first see Killmonger, standing resplendent in his shearling coat in the Museum of Great Britain. He knows something that the coffee-sipping museum curator does not – the ancient axe taken by British soldiers in Benin is actually from Wakanda. The British have no claim to this vibranium axe; ideally, now as before, it should be in Wakanda. Of course, it’s not in Wakanda and the British do have it, so now what? How do we get there from here? Is it “anything goes” as long as the axe gets back to its rightful owners? As a Wakandan, does Killmonger have the right of repossession? Do the curator and other museum staff deserve punishment for their crimes?

“Don’t Sweat, I’m Gonna Take It Off Your Hands for You.”

Perhaps the most obvious way to correct an injustice is to restore the material conditions prior to it: as Archbishop Desmond Tutu put it, “If you take my pen and say you are sorry but don’t give me the pen back, nothing has happened.”6 Restitution seems an especially natural response to theft or fraud, whether it’s money, a pen, or a centuries-old axe. In other situations, though, putting things back as they were is impossible; try as you might, you can’t unscramble the egg or put the toothpaste back in the tube. T’Challa, N’Jadaka, W’Kabi –none of them can get their fathers back. Wakanda could open its arms to the long-lost N’Jadaka, long abandoned by his uncle T’Chaka, but the years of neglect cannot really be compensated for.

Indeed, the aim of restoring material conditions to the way they were often seems inappropriate or at least insufficient in response to wrongdoing. If one person accidentally takes my pen and another steals it, they should both return my pen. But doesn’t the latter owe me something more than the former, something that differentiates theft from an honest mistake? The material conditions disrupted by injustice are surely relevant to correction, but for serious historical injustices, is putting things back as they were an adequate response?

The case for restitutive justice at the museum is pretty strong, but Killmonger does a poor job of it: like his brief reign as king, his corrective justice begets further injustice. The axe doesn’t just belong to him, so other Wakandans may rightly object to him partnering with Klaue and selling it to the highest bidder (the CIA) in Korea. His crew preemptively poisons and shoots museum staff before any effort to argue their right of repossession. And to add insult to injury, Killmonger swipes a traditional African mask as he makes his escape. (“You’re not telling me that’s vibranium too?” “Nah, I’m just feeling it.”) Chances are the Museum of Great Britain has no more of a claim to that mask than to the vibranium axe, of course, but whoever deserves to have it and to be made whole again, it’s not Killmonger and Klaue.

“How Do You Think Your Ancestors Got These?”

Maybe we’re focused on the wrong sort of desert. Maybe we should consider retribution rather than restitution. The British took the mask like they took the axe and deserve punishment for it. Killmonger and Klaue aren’t repo men, they’re the executioners of retributive justice. (Well, not Klaue. He seems happy just as an agent of chaos.) “The world took everything away from me, everything I ever loved!” Killmonger declares in his righteous anger. “But I’mma make sure we’re even.” He’s not talking about restitutive justice here. He wants to punish the world.

Killmonger is not the only character in Black Panther for whom retribution as corrective justice resonates deeply. T’Challa goes to Korea to capture Klaue, bring him to Wakanda to stand trial, and complete his father’s unfinished work. Eager to apprehend his parents’ killer, W’Kabi asks to join in. When T’Challa gently refuses, W’Kabi makes his priorities clear: “Then I ask – you kill him where he stands or you bring him back to us.” T’Challa fails to do either, Killmonger arrives with Klaue’s body, and this sways W’Kabi to the usurper’s cause. “I am standing in your house, serving justice to a man who stole your vibranium and murdered your people,” Killmonger says. “Justice your king couldn’t deliver.”

Has justice been served? The philosopher Alec Walen identifies three core principles serving as the foundation of retributive justice:

1 those