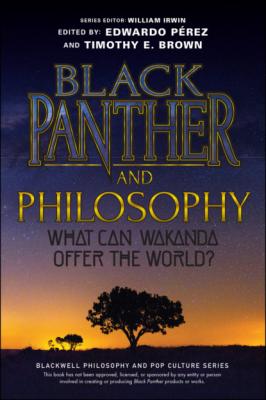

Black Panther and Philosophy. Группа авторов

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Black Panther and Philosophy - Группа авторов страница 20

who gets to decide what is the right way to behave: we have our way, but we cannot impose it on others.

who gets to decide what is the right way to behave: we have our way, but we cannot impose it on others.

Here we see a glimpse of the way Wakanda chooses a different path from their Western contemporaries. We are invited to take the view that Wakanda is on the moral high ground because they do not use their technological strength to conquer or dominate others. This is indeed virtuous, but refusing to assist refugees or other states while they were colonized and sent into slavery is evidence of an extreme commitment to prioritizing one’s own interests. Wakanda’s foreign policy is extreme isolation, a position that is questioned by individuals at various moments, but appears to be largely accepted as the societal norm. How does this portrayal sit with what we do know about traditional African societies, and what contemporary African scholars suggest as possible modern-day applications of their traditional values?

What about African Philosophy?

W’Kabi speaks in isiXhosa, but has he heard of ubuntu? IsiXhosa is a Bantu language of the Xhosa people, spoken mainly in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Beyond South Africa, some may have heard of the term ubuntu, whether it be through using the open-access software by that name, following the vibrant former Archbishop Desmond Tutu, or receiving something like a gift soap or tea labelled as Ubuntu soap! The typical South African will have grown up with the moral ethic of ubuntu as a commonplace feature: “I am because we are, and since we are, therefore, I am,” motho ke motho ka batho babang (isiXhosa); umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu (isiZulu).3 Afro-Canadian philosopher Edwin Etieyibo explains, “Ubuntu reflects the life experiences and histories of people in sub-Saharan Africa and defines the individual in terms of humanity or interdependency with others.”4

In African philosophy, scholars often analyze or draw from proverbs and language use as a way to explore moral and political principles within an oral tradition. Because the characters of Wakanda are speaking a traditional African language, it is particularly important to consider proverbs and linguistic usage. Certain principles and approaches to life are contained within the language, the way of speaking. It is striking therefore that the character W’Kabi speaks isiXhosa but seems not to have heard of one of its key guiding values. Let me elaborate.

Philosophers in recent decades have explored the concept of ubuntu to unpack its moral and philosophical implications and to consider its modern-day application. A core idea of ubuntu is that one’s humanity is intricately bound up with the humanity of the other. As Etieyibo observes, in order to be a person, one has to establish “human relations.”5 To be human, as ubuntuism holds, is to “affirm one’s humanity by recognizing the humanity of others and, on that basis, establish relations with them.”6 Basic terms of such a relationship are expressed in the form of toleration, sharing, charity, respect, acceptance, hospitality, compassion, reconciliation, empathy, and reciprocity.7 Or, as T’Challa says in the closing scene of the film, “We must find a way to look after one another as if we were one single tribe.”

To be sure, traditional African societies were not homogeneous, nor were they entirely peaceful. Philosophers do not want to claim that all Africans lived in the perfect spirit of ubuntu before colonial interventions. Indeed, wars between different groups were common.8 African philosophers also do not want to argue that pre-intervention society was inherently good and worthy of emulating. Such a “narrative of return,” which essentializes what it means to be African and values principles only because they are traditional, would be misguided.9 We can think here of how T’Challa comes to believe the traditional ways of his ancestors were wrong. Yet, we should nevertheless engage with what seems historically to have been a way of seeing the world and organizing society and consider the underlying values and their potential – especially when those philosophies and ways of life have typically been erased. In what follows, I present three examples of African philosophy on the question of our global duties, and highlight how they feature core values of relatedness, mutuality, and a sense of shared humanity.

“More Connects Us than Separates Us”

Etieyibo argues that if we unpack the concept of ubuntu, and the fact that we are persons through our recognition of others’ humanity, then we should be drawn toward a cosmopolitan view: a view that holds the scope of our moral obligations is not affected by state (or other) boundaries.10 While ubuntu was traditionally practiced in small communities, Etieyibo argues that the underlying philosophy does not have any grounds to justify it having to be only practiced within small communities. Ubuntu is based on our shared humanity, not on our shared kinship: it is I am because you are, not “I am because you are my cousin, or clansperson.”

Some argue that today we are at the “end of ubuntu” for various reasons, including the strategic use and manipulation of the concept by politicians.11 Part of the argument is that we no longer have the small communities required to make ubuntu work. Yet, we do not have the counterfactual example of how ubuntu would have adapted to the slow creation of larger communities and industrialization. So we cannot tell how much of the corrosion of the practice of ubuntu and its defining role in society is because of colonialist intervention and how much is down to the reality of living in large cities.

Of course, it seems reasonable to agree that ubuntu as practiced in a small-scale community would not function in the same way. But, is there a way the underlying values of ubuntu – the valuing of mutuality, compassion, respecting, and recognizing the humanity of the other – would have grown and adapted to being the guiding principles of a modern African state? Why did the creators of Wakanda not use this opportunity to imagine such a state? Given its centrality in considerations of the morality of the people of sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in Bantu-speaking communities, it is surprising that the proverb, word, or spirit seems largely lost in the Wakanda we find at the beginning of the film.

African Philosopher Michael O. Eze argues that ubuntu provides a foundation for a society that welcomes difference, that lays the groundwork for a “new paradigm of human citizenship that is both universal and provincial” where “we do not have the dilemma of choosing our own kind over the stranger for even the stranger is a potential relative.”12 This account speaks not to the tearing down of all borders or notions of community, but to viewing the rooted community as fundamentally open to others. Indeed, ubuntu can provide a new, stronger grounding for a cosmopolitan theory.

Traditionally in Western thought, the basis for a cosmopolitan view is that we are all fellow human beings and thus of equal moral worth. Human beings have been defined as those who share the quality of being able to reason. Eze argues that this Western cosmopolitanism, as is seen through colonialism, is “not so much about elimination of difference but an invention of a homogenous other.”13 Reason, Eze argues, is provincial: it can be dominated by culture, religion, and other features of our context.14 It is not a reliable ground for a truly cosmopolitan theory. Eze argues instead that ubuntu, and its inherent relatedness, can do much better in justifying a cosmopolitan worldview, adding that ubuntu grounds a duty to “recognize others in their unique difference, histories and subjective equations” and that this sense of humanism “is not only a recognition of our kind.”15

While cosmopolitanism based on reason requires recognizing in others the same ability to reason, a so-called Xerox of my being, the ethics of ubuntu in fact thrives on difference: “the other constitutes an inexhaustible source of our reason to be.”16 Human interaction is a mutual self-creating process, and there is nothing within the concept of ubuntu that prioritizes the recognition and interaction with those of “our own kind” over the other.17 In fact, Eze argues that traditional communities would welcome the stranger and grant them epistemic preference (view them as the superior bringer of knowledge) because of their access to fresh ideas.18 This interaction is motivated, Eze claims, by a “desire of harmonization