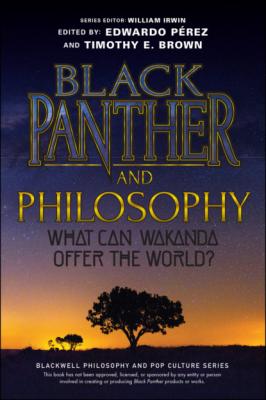

Black Panther and Philosophy. Группа авторов

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Black Panther and Philosophy - Группа авторов страница 22

style="font-size:15px;"> 9 9. Bernard Matolino and Wenceslaus Kwindingwi, “The end of Ubuntu,” South African Journal of Philosophy 32 (2013), 197–205.

style="font-size:15px;"> 9 9. Bernard Matolino and Wenceslaus Kwindingwi, “The end of Ubuntu,” South African Journal of Philosophy 32 (2013), 197–205.10 10. Etieyibo.

11 11. Matolino and Kwindingwi.

12 12. Eze, 98.

13 13. Eze, 101.

14 14. Eze, 100.

15 15. Eze, 100.

16 16. Eze, 101.

17 17. Eze, 101.

18 18. Eze, 100.

19 19. Eze, 100.

20 20. Ifeanyi A. Menkiti, “Africa and global justice,” Philosophical Papers 46 (2017), 23.

21 21. Menkiti, 23.

22 22. Menkiti, 23.

23 23. Menkiti, 24.

24 24. Menkiti, 24.

25 25. Menkiti, 28.

26 26. Menkiti, 28.

27 27. This chapter would not have been possible without the interesting conversations with my Philosophy Honours classes at the University of Fort Hare, Alice, South Africa 2018 & 2019. Thanks are also owed to Stephen Cooke, Vuyani Ndzishe, and Ryan Roos, who commented on earlier drafts of this chapter.

5 T’Challa’s Liberalism and Killmonger’s Pan-Africanism

Stephen C.W. Graves

“Wakanda Forever” is the most memorable phrase from Black Panther, but what does it really mean? Given Wakanda’s isolationist attitude and deep-seated sense of nationalism, it seems to mean “Wakanda for the Wakandans!” As portrayed in the film, this nationalism was constructed as a defense against the outside world. After all, as W’Kabi, who opposes accepting refugees from neighboring countries, says, “The problem with refugees is they bring their problems with them.”

In brief, the history of Wakanda began thousands of years ago when five African tribes fought over a meteorite containing vibranium. United as Wakanda, they used the vibranium to develop advanced technology and isolate themselves from the world, posing as a third-world country. Ultimately, a visit from Thanos’s army in Avengers: Infinity War led to the decision that Wakanda could no longer isolate from the rest of the world. As a result, nationalism gave way to liberalism.

Liberalism, as an international theory, encourages cooperation among nations for the sake of mutual benefits. The protection and promotion of human rights and freedom must come ahead of national interests and state autonomy. The hope is that war can be prevented or eliminated through institutional reform or collective action.1 But does liberalism suffice? Perhaps a Pan-African alternative is preferable.

“Wakanda Has the Tools to Liberate’em All.”

In 1992, N’Jobu planned an armed assault on the California National Guard in response to the beating of Rodney King and the Los Angeles uprising that ensued. He further planned to share Wakanda’s technology with people of African descent around the world to help them throw off their oppressors. N’Jobu’s plans were thwarted, but in 2016 N’Jobu’s son, Killmonger, planned to share Wakandan weapons with operatives around the world.

After the death of his father at the hands of the former king T’Chaka, Killmonger grew up an orphan in poverty. His experiences of racial discrimination, the war on drugs waged in Black neighborhoods, over-policing, systemic poverty, and redlining, led him to the belief that Wakanda’s advanced technology should serve the purpose of liberating oppressed African people around the globe.

Killmonger’s philosophy of spreading Wakanda’s wealth and technological advances to Black communities all over the world aligns with the Pan-African vision of such nationalists as Martin Delany, Marcus Garvey, and Malcolm X. The term “Pan-African” dates to the first Pan-African Conference, held in London in July 1900. The conference aimed to assemble “men and women of African blood, to deliberate solemnly upon the present situation and the outlook for the darker races of mankind” and to demonstrate that those of African descent could speak for themselves. Its “Address to the Nations of the World” condemned racial oppression in the United States, as well as throughout Africa, and demanded self-government for Britain’s colonies.

W.E.B. Du Bois sought to continue the tradition of those of African descent speaking with one voice when he organized his own Pan-African Congress in Paris in 1919. Du Bois took the initiative to organize a second congress, held in 1921 in London, Paris, and Brussels, a third in London and Lisbon in 1923, and a fourth in New York in 1927. The congresses took a stand against racism and raised the demand for self-determination. They were, however, criticized as harboring moderate political views and for their exclusion of Marcus Garvey, perhaps the leading Pan-Africanist of the time.

Garvey had established his Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League in Jamaica in 1914. Among its aims were “a universal confederacy amongst the race.”2 Time only strengthened Pan-African demands for an end to colonial rule. In Britain, George Padmore, Amy Ashwood Garvey, and the Pan-African Federation made preparations for a new gathering at the Manchester Pan-African Congress of 1945. The Manchester Pan-African congress of October 1945 marked a turning point in the history of the Pan-African movement. Since this meeting, the struggle for the emancipation of people of African descent focused on the continental homeland. When Kwame Nkrumah returned to Ghana in December 1947, Pan-Africanism moved into the realm of practical politics. With Ghana achieving independence in March 1957, and until the creation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU, May 1963), Ghana became the focal point of the struggle for African unity, with Kwame Nkrumah as the unofficial leader.

According to Nkrumah, political integration is a prerequisite for economic integration. As Nkrumah states, “unless Africa is politically united under an all-African union government, there can be no solution to our political and economic problems. We are Africans first and last, and as Africans our best interests can only be served by uniting within