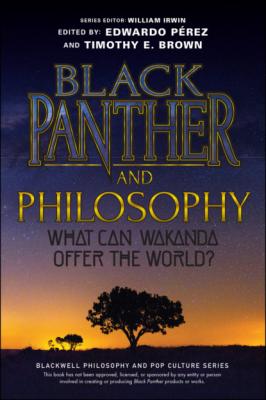

Black Panther and Philosophy. Группа авторов

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Black Panther and Philosophy - Группа авторов страница 17

is intrinsically morally good – good without reference to any other goods that might arise – if some legitimate punisher gives them the punishment they deserve;

is intrinsically morally good – good without reference to any other goods that might arise – if some legitimate punisher gives them the punishment they deserve;3 it is morally impermissible intentionally to punish the innocent or to inflict disproportionately large punishments on wrongdoers.7

Now consider: the stolen vibranium has not been returned, W’Kabi’s parents are still dead, and none of those directly or indirectly responsible for these things have done anything to compensate for that. But for Killmonger and W’Kabi (and no doubt many other Wakandans) what matters is that Klaue has been punished for his grievous crimes. The intrinsic good of retribution remains. If anyone deserves death as proportionate punishment for their wrongful acts, Klaue for his 1991 homicides (not to mention grand theft) is among them. Is Killmonger a “legitimate punisher” in this case? Most of the assembled Wakandan Council seem skeptical when he arrives with Klaue, but then they don’t know who he really is. (“That’s not my name princess. Ask me, king.”)

“In Times of Crisis, the Wise Build Bridges.”

Despite popular assumptions, reparative justice is not really about monetary payments for historical injustice; “the fundamental issue in reparations,” the philosopher Margaret Urban Walker writes, “is the moral vulnerability of victims of serious wrongs.”8 Sure, if you want to do right by me after, it matters how you hurt me – you’ve stolen my car, destroyed my garden, appropriated my culture’s artifacts to add to your museum collection. But for those who believe in reparative or restorative justice, “the harm done is only peripherally about ‘stuff.’ Instead, the harm is understood in the relational realm.”9

Thinking of it this way, reparative justice doesn’t ask us to look backwards, but to do what we can to repair our moral relationships and our communities that have been hurt by historical and ongoing injustices. Admitting and apologizing for our role in wrongdoing and making amends matter because they do the work of relational repair. The key to reparative justice is communication between those who commit injustice and those who are hurt by it. Amends aren’t charity or compensation for what’s been lost. They work because of the “expressive burden”10 they carry: their ability to convey my regret, my acknowledgement of wrongdoing, and most of all, my recognition of those I hurt as full members of our shared moral community, as deserving of respect and consideration as anyone else.

And yet relational repair is not always achievable. Some victims are unable to forgive; some perpetrators fail to acknowledge or even realize their wrongdoings, and among those who do, some cannot bring themselves to apologize or do what’s needed to make amends. There’s no real sense that the British recognize their appropriation of African artifacts as wrong, so until they do, is it reasonable to ask Wakandans or other Africans to begin working toward relational repair? Or recall the last exchange between a defeated Killmonger and a victorious T’Challa, who carries his wounded cousin into the fading evening light.11 “Maybe we can still heal you,” T’Challa offers; maybe reconciliation is still possible. But Killmonger refuses. His self-respect and dignity won’t allow him to accept the bondage of incarceration – and his colonizer’s mentality won’t allow him to imagine anything else.

Though we’ve considered restitution, retribution, and reparation one by one, these responses to historical and ongoing injustices aren’t mutually exclusive. People and institutions often react to injustice with a mixture of these – or we might find ourselves reacting to injustice in a way that doesn’t include any of them or that ignores the need for corrective justice altogether. In Black Panther, T’Chaka, Killmonger, and Nakia offer radically different visions for Wakanda after injustice, visions for our hero – and for us – to reckon with.

T’Chaka’s Isolationism and Active Ignorance

T’Challa loved his father, but he never really knew him, and in his ignorance he was not alone. King T’Chaka kept nearly all Wakandans in the dark about what happened in Oakland and about the boy he left there. “We had to maintain the lie,” Zuri explains to an unconvinced T’Challa. Or as T’Chaka himself says of his decision to abandon his brother’s son, “He was the truth I chose to omit.”

This was his political philosophy and his epistemology, isolationism and ignorance as two sides of one coin. Whatever else he accomplished as king, T’Chaka produced what the historian of science Robert Proctor calls ignorance as an active construct12 : a kind of not-knowing, though not because life is short and there is just so much to know. With active ignorance, the not-knowing is the point. Sometimes we actively construct our own ignorance, but here T’Chaka is more like tobacco companies that worked for decades to manufacture public doubt about cigarettes, cancer, and addiction.13 He knows full well what he’s done, but thinks protecting his people means hiding the truth from them.

T’Chaka constructs public ignorance to uphold an isolationist vision for Wakanda. Think about W’Kabi’s advice to T’Challa on the question of aiding the world. “You let the refugees in, they bring their problems with them, and then Wakanda is like everywhere else.” Yet “their” problems are Wakanda’s problems too. The abandoned N’Jadaka is the truth T’Chaka chose to omit, a truth hidden from W’Kabi and other Wakandan isolationists – that “our” people are out there too. This is what the journalist Adam Serwer identifies as Black Panther’s central theme of Pan-Africanism: “a belief that no matter how distant black people’s lives and struggles are from each other, we are in a sense ‘cousins’ who bear a responsibility to help one another escape oppression.”14

Killmonger’s Imperialism and the Master’s Tools

Black Panther was a huge hit, with a $200 million opening weekend US box office on its way to staggering total grosses of $700 million domestically and $1.3 billion worldwide. And the hashtag that was trending on Twitter that spring? #KillmongerWasRight.

Killmonger wasn’t raised behind T’Chaka’s carefully constructed wall of ignorance. In many ways he knew more truth than anyone about Wakanda, about what it had done and what it could do to upend the world’s balance of power. Yet the danger of single-minded devotion to corrective justice as retribution is that it needs offenders to punish. Killmonger was able to give W’Kabi some level of satisfaction against Klaue, but what about his own claim of retribution against T’Chaka? The king who killed his brother and abandoned his nephew is gone, so who is left for Killmonger to serve justice to? “The world,” he answers, as the foundations of his claim to corrective justice erode and retribution becomes untethered from any legitimate or proportionate punishment. Killmonger’s vengeance is let loose.

Vengeance is not justice,15 but it’s not always easy to tell them apart. Perhaps no one knows this better than T’Challa, who emerges from the pain and loss of Civil War with this resolve. Having nearly killed Bucky Barnes, he tracks down the man truly responsible for his father’s death, Helmut Zemo, just as Zemo’s ultimate plan is nearly complete: he has turned Captain America and Iron Man against each other. “Vengeance has consumed you. It is consuming them. I am done letting it consume me.” T’Challa tells Zemo. “Justice will come soon enough.” It’s a hard-won lesson; if only he could share it with his long-lost cousin.

Deprived of his father and Wakandan community, N’Jadaka availed himself of the resources he did have and built himself into the mighty Killmonger we meet in the film. What resources? The Naval Academy, MIT, SEALs – “Killmonger is not a product of the ghetto,” Serwer explains, “so much as he is the product of the American military-industrial complex.”16 Many viewers see Killmonger as a damning depiction of Black American masculinity, for better or for worse. Indeed, the philosopher Christopher Lebron criticizes the film, saying that