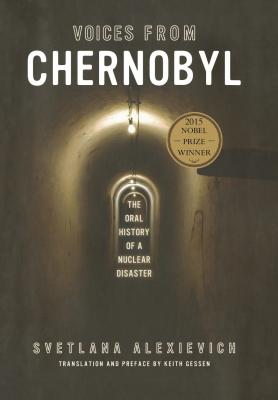

Voices from Chernobyl. Светлана Алексиевич

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Voices from Chernobyl - Светлана Алексиевич страница 6

myself, when there’s two of us?”

myself, when there’s two of us?”

“In that case, if it’s a boy, he should be Vasya, and if it’s a girl, Natasha.”

I had no idea then how much I loved him! Him . . . just him. I was like a blind person! I couldn’t even feel the little pounding underneath my heart. Even though I was six months in. I thought that my little one was inside me, that he was protected.

None of the doctors knew I was staying with him at night in the bio-chamber. The nurses let me in. At first they pleaded with me, too: “You’re young. Why are you doing this? That’s not a person anymore, that’s a nuclear reactor. You’ll just burn together.” I was like a dog, running after them. I’d stand for hours at their doors, begging and pleading. And then they’d say: “All right! The hell with you! You’re not normal!” In the mornings, just before eight, when the doctors started their rounds, they’d be there on the other side of the film: “Run!” So I’d go to the dorm for an hour. Then from 9 A.M. to 9 P.M. I have a pass to come in. My legs were blue below the knee, blue and swollen, that’s how tired I was.

While I was there with him, they wouldn’t, but when I left—they photographed him. Without any clothes. Naked. One thin little sheet on top of him. I changed that little sheet every day, and every day by evening it was covered in blood. I pick him up, and there are pieces of his skin on my hand, they stick to my hands. I ask him: “Love. Help me. Prop yourself up on your arm, your elbow, as much as you can, I’ll smooth out your bedding, get the knots and folds out.” Any little knot, that was already a wound on him. I clipped my nails down till they bled so I wouldn’t accidentally cut him. None of the nurses could approach him; if they needed anything they’d call me.

And they photographed him. For science, they said. I’d have pushed them all out of there! I’d have yelled! And hit them! How dare they? It’s all mine—it’s my love—if only I’d been able to keep them out of there.

I’m walking out of the room into the hallway. And I’m walking toward the couch, because I don’t see them. I tell the nurse on duty: “He’s dying.” And she says to me: “What did you expect? He got 1,600 roentgen. Four hundred is a lethal dose. You’re sitting next to a nuclear reactor.” It’s all mine . . . it’s my love. When they all died, they did a remont at the hospital. They scraped down the walls and dug up the parquet.

And then—the last thing. I remember it in flashes, all broken up.

I’m sitting on my little chair next to him at night. At eight I say: “Vasenka, I’m going to go for a little walk.” He opens his eyes and closes them, lets me go. I just walk to the dorm, go up to my room, lie down on the floor, I couldn’t lie on the bed, everything hurt too much, when already the cleaning lady is knocking on the door. “Go! Run to him! He’s calling for you like mad!” That morning Tanya Kibenok pleaded with me: “Come to the cemetery, I can’t go there alone.” They were burying Vitya Kibenok and Volodya Pravik. They were friends of my Vasya. Our families were friends. There’s a photo of us all in the building the day before the explosion. Our husbands are so handsome! And happy! It was the last day of that life. We were all so happy!

I came back from the cemetery and called the nurse’s post right away. “How is he?” “He died fifteen minutes ago.” What? I was there all night. I was gone for three hours! I came up to the window and started shouting: “Why? Why?” I looked up at the sky and yelled. The whole building could hear me. They were afraid to come up to me. Then I came to: I’ll see him one more time! Once more! I run down the stairs. He was still in his bio-chamber, they hadn’t taken him away yet. His last words were “Lyusya! Lyusenka!” “She’s just stepped away for a bit, she’ll be right back,” the nurse told him. He sighed and went quiet. I didn’t leave him anymore after that. I escorted him all the way to the grave site. Although the thing I remember isn’t the grave, it’s the plastic bag. That bag.

At the morgue they said, “Want to see what we’ll dress him in?” I do! They dressed him up in formal wear, with his service cap. They couldn’t get shoes on him because his feet had swelled up. They had to cut up the formal wear, too, because they couldn’t get it on him, there wasn’t a whole body to put it on. It was all—wounds. The last two days in the hospital—I’d lift his arm, and meanwhile the bone is shaking, just sort of dangling, the body has gone away from it. Pieces of his lungs, of his liver, were coming out of his mouth. He was choking on his internal organs. I’d wrap my hand in a bandage and put it in his mouth, take out all that stuff. It’s impossible to talk about. It’s impossible to write about. And even to live through. It was all mine. My love. They couldn’t get a single pair of shoes to fit him. They buried him barefoot.

Right before my eyes—in his formal wear—they just took him and put him in that cellophane bag of theirs and tied it up. And then they put this bag in the wooden coffin. And they tied the coffin with another bag. The plastic is transparent, but thick, like a tablecloth. And then they put all that into a zinc coffin. They squeezed it in. Only the cap didn’t fit.

Everyone came—his parents, my parents. They bought black handkerchiefs in Moscow. The Extraordinary Commission met with us. They told everyone the same thing: it’s impossible for us to give you the bodies of your husbands, your sons, they are very radioactive and will be buried in a Moscow cemetery in a special way. In sealed zinc caskets, under cement tiles. And you need to sign this document here.

If anyone got indignant and wanted to take the coffin back home, they were told that the dead were now, you know, heroes, and that they no longer belonged to their families. They were heroes of the State. They belonged to the State.

We sat in the hearse. The relatives and some sort of military people. A colonel and his regiment. They tell the regiment: “Await your orders!” We drive around Moscow for two or three hours, around the beltway. We’re going back to Moscow again. They tell the regiment: “We’re not allowing anyone into the cemetery. The cemetery’s being attacked by foreign correspondents. Wait some more.” The parents don’t say anything. Mom has a black handkerchief. I sense I’m about to black out. “Why are they hiding my husband? He’s—what? A murderer? A criminal? Who are we burying?” My mom: “Quiet. Quiet, daughter.” She’s petting me on the head. The colonel calls in: “Let’s enter the cemetery. The wife is getting hysterical.” At the cemetery we were surrounded by soldiers. We had a convoy. And they were carrying the coffin. No one was allowed in. It was just us. They covered him with earth in a minute. “Faster! Faster!” the officer was yelling. They didn’t even let me hug the coffin. And—onto the bus. Everything on the sly.

Right away they bought us plane tickets back home. For the next day. The whole time there was someone with us in plainclothes with a military bearing. He wouldn’t even let us out of the dorm to buy some food for the trip. God forbid we might talk with someone—especially me. As if I could talk by then. I couldn’t even cry. When we were leaving, the woman on duty counted all the towels and all the sheets. She folded them right away and put them into a polyethylene bag. They probably burnt them. We paid for the dormitory ourselves. For fourteen nights. It was a hospital for radiation poisoning. Fourteen nights. That’s how long it takes a person to die.

At home I fell asleep. I walked into the place and just fell onto the bed. I slept for three days. An ambulance came. “No,” said the doctor, “she’ll wake up. It’s just a terrible sleep.”

I was twenty-three.

I remember the dream I had. My dead grandmother comes to me in the clothes that we buried her in. She’s dressing up the New Year’s tree. “Grandma, why do we have a New Year’s tree? It’s summertime.” “Because your Vasenka is going to join me soon.” And he grew up in the forest. I remember the dream—Vasya comes in a white robe and calls for Natasha. That’s our girl, who I haven’t given birth to yet.